Family tree: Ornithodira > Pterosauria > Pterodactyloidea > Azhdarchiformes > Azhdarchidae

Hometown: Worldwide, Cretaceous Period (108-66 million years ago)

Described 1984

Azhdarchids (as-DAR-kids) were a sub-group of pterosaurs (flying reptiles) that lived at the end of the Age of Reptiles and pushed the boundaries of what a flying animal could be. Whereas earlier in the Triassic and Jurassic, pterosaurs came in all shapes and sizes and often filled niches that are reminiscent of what certain birds or bats do today (such as nocturnal insect eating, filter feeding, or mud probing, for example), by the Cretaceous Period, birds had diversified enough to push pterosaurs away from those familiar roles and into ones that simply don’t exist today. Azhdarchids were the largest animals ever to fly, with twelve-plus-meter (39-plus foot) wingspans and weighing up to a quarter tonne (550 lbs). They walked, launched, flew, and hunted prey on the ground in ways no animal does today. The closest thing today would be a Great Blue Heron or Shoebill Stork (if they were 35 times heavier), or a predatory giraffe.

By now I hope you’ve seen Prehistoric Planet 2 on Apple TV+. It’s a series of five nature documentaries narrated by Sir David Attenborough that take place in the latest Cretaceous, 66 million years ago, using beautiful computer animation to bring ancient animals to life. The scientific advisors on the project are some real paleo rockstars, such as artist / researcher Mark Witton and paleontologist Darren Naish of All Yesterdays fame. Therefore, the animals pictured are quite diverse, believable, and up-to-the-minute accurate.

While pterosaurs appeared frequently in the first season, such as the Barbaridactylus colony showing the difference between the showy and the sneaky males and also hunting flapling Alcione, Quetzalcoatlus nesting, and the unnamed pterosaurs roosting on cliffs (which appear as a reused character model in PP2–read on), they weren’t shown off quite as heavily as they are in the second season. Azhdarchids are now not only the main characters in many of the scenes, but are romanticized in their abilities a bit too far. While they certainly are really cool animals unlike anything that exists today, I think the paleontologist advisors had a little bit of an agenda in emphasizing their prowess.

In this post, I’ll describe what azhdarchid pterosaurs were and what they could do, and compare and contrast with what they are shown doing in Prehistoric Planet 2.

Could Hatzegopteryx carry a dinosaur from island to island?

During the Cretaceous Period, most of Europe was flooded, leaving chains of islands full of dwarf relatives of mainland giants, and giant versions of mainland small-bodied animals. (For a good explanation of insular dwarfism and gigantism, see this Common Descent Podcast episode.)

Tethyshadros was one of these island dwarves, weighing as much as a small horse or large pig, half to a sixth the weight of its mainland relatives. Its smaller size was likely an adaptation to the limited amount of food available on the islands on which it evolved, and a response to the lack of large predators like tyrannosaurs and abelisaurs that threatened herbivores elsewhere. However, one large predator was able to cross the channels separating the islands and specialize in devouring the otherwise peaceable island dwarves: Hatzegopteryx.

While Hatzegopteryx was not the tallest azhdarchid, it was probably the heaviest, being much more robustly built than the other giants Quetzalcoatlus and Arambourgiania, with a shorter and thicker neck [1]. This was probably an adaptation to tackling larger prey, which is exactly what it’s shown doing: snatching up baby Tethyshadros. The entire scene is basically a dramatic reenactment of the paper published by the scientific advisors Darren Naish and Mark Witton in 2017 which analyzed the strength of a Hatzegopteryx neck vertebra. The show states that the Tethyshadros weighs 40 pounds (18 kg), well within the bounds of what Hatzegopteryx could pick up comfortably. So far, so good.

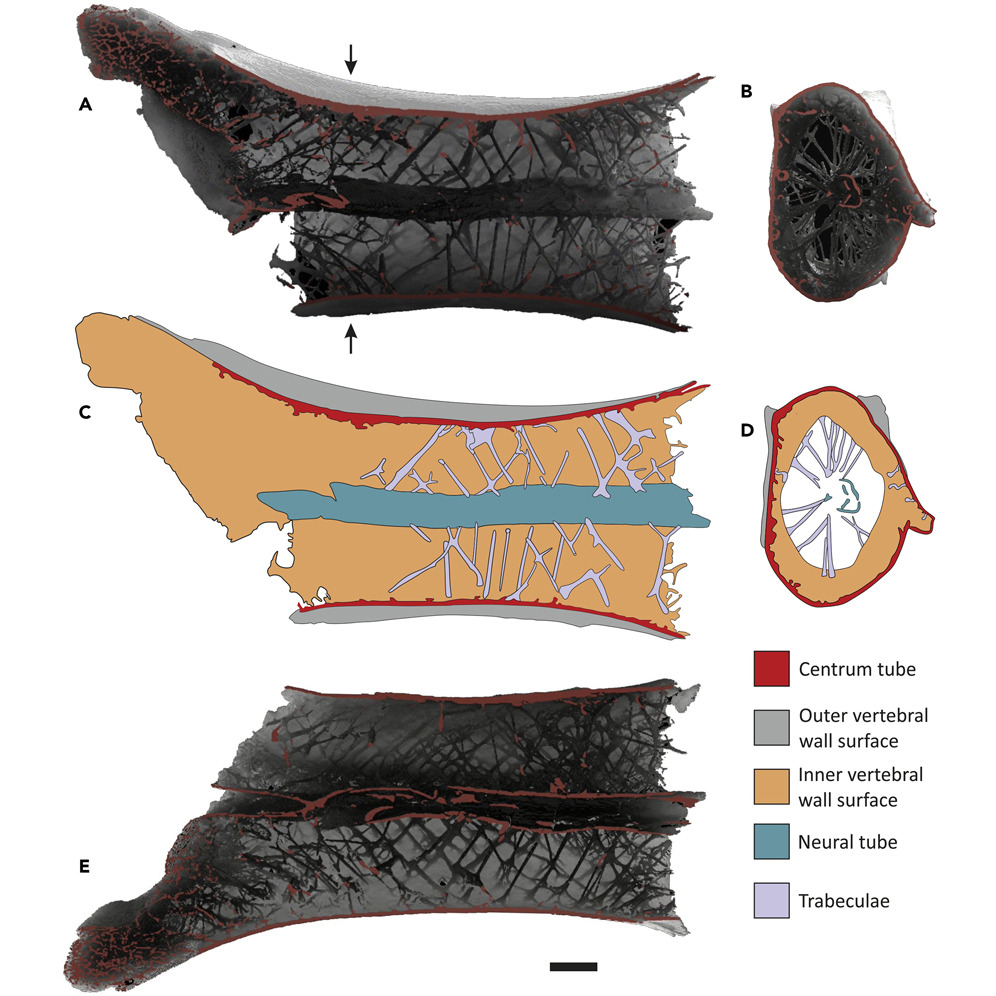

In addition to the readily apparent stoutness of its vertebrae, a recently CT-scanned vertebra from a related azhdarchoid, Alcione, was shown to have internal bicycle spokes–that is, there was a central tube housing the spinal cord, an outer tube forming the visible fossil bone surface, and in between hundreds of bony spokes [2]. This arrangement is extremely strong and light, which is why we use it for bicycles. In bikes, the spokes are pulled taut, causing the rider to be essentially supported by the top half of the wheel rather than from below. I’m not sure if that is how pterosaur vertebrae worked as well, but given the thinness of the struts it’s probable that the same mechanics are at play. If the struts were in compression rather than tension, they would probably buckle.

Predatory birds today tend to have hooked beaks, or at least a small downturned “nail” on the end of the bill that keeps struggling prey from slipping forward out of the mouth. The pterosaurs in Prehistoric Planet are depicted as lacking such a feature, yet still managing to snatch up heavy, struggling prey with ease. This depiction is consistent with the shape of their fossilized skulls and the osteological correlates on those skulls that indicate what kind of keratin or other tissue covered it in life. But if they lacked a hooked bill, how did they keep prey in their mouths? Probably with a serrated tongue and roof of the mouth (known as papillae), similarly to penguins.

However, no pterosaur mouth soft tissue fossils have ever been found, so we aren’t sure whether this was the case. In Prehistoric Planet, the inside of azhdarchid mouths isn’t really shown. I think that’s a shame, as this would have been a cool detail to include.

So, we’ve established that Hatzegopteryx could pick up the dinosaur as shown. But could it then fly while carrying it? And could it fly across a fairly large body of water with it?

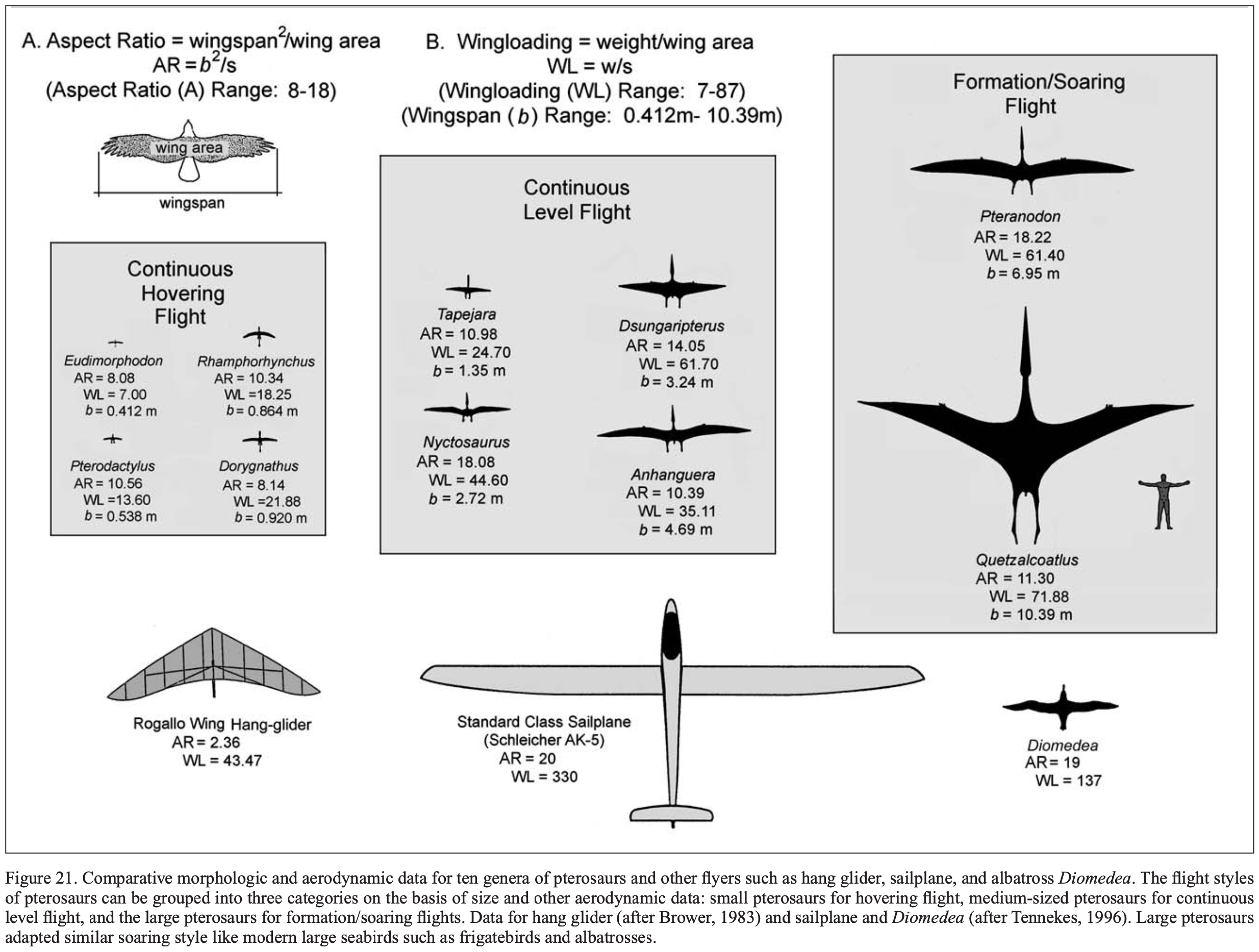

Flight mechanics are quite complicated and depend on a variety of factors. The main ones are wing loading, which is just body weight divided by wing area, and wing aspect ratio, with a high aspect ratio indicating long, thin wings and a low one indicating short, broad wings. These two factors influence flight strategy, such as thermal soaring (circling on a rising warm air current to gain height, then gliding to where you want to go) versus dynamic soaring (catching lots of small updrafts created by wind hitting vertical features such as wave crests or cliffs) versus sustained flapping. Finally, ground incline and wind speed influence whether takeoff is possible, with some heavier fliers like albatrosses unable to take off uphill or in still air. Multiple researchers have attempted to determine what aerial feats pterosaurs and extinct birds were capable of, but with all these factors in play it’s hard to do more than basic generalizations. Note that these studies use Quetzalcoatlus northropi as their model pterosaur, not Hatzegopteryx, due to the former’s much more complete skeletal remains, but we can assume that Hatzegopteryx’s flying abilities would have been similar or slightly worse.

For Quetzalcoatlus, continuous level flapping flight was simply not possible, since the speed required to generate sufficient lift to not lose any altitude would require way too much energy output to maintain [3]. So, it must have been forced to use one of the above-mentioned strategies, thermal soaring or dynamic soaring, to gain height, or to take off into a stiff wind or by jumping off a ledge. However, when scientists modeled its gliding capabilities, Quetzalcoatlus performed worse than the Kori Bustard, the heaviest (rarely) flighted bird today.

In soaring, there are two phases: the ascent phase and the glide phase. Broad, eagle-like wings perform better in the ascent phase, while long, albatross-like wings perform better in the gliding phase. That’s why old man-made gliders, like the Rogallo wing shown in the infographic above, had broad wings while modern gliders, which can take advantage of high-power-output motors for the takeoff, have ridiculously long thin wings to minimize the rate of altitude loss.

Quetzalcoatlus, on the other hand, had broad wings rather than long wings, indicating that it needed that boost to even get into the air, but would have further sacrificed gliding efficiency. [4] Hatzegopteryx, with its heavier skull and stouter body, would have fared even worse, and would probably only have been capable of short flights. Between closely-spaced islands where you can always see the next stop? Maybe. But crossing vast stretches of ocean? Certainly not. In Prehistoric Planet, the islands it’s shown landing on do have visibility to the next island. For a five-meter-tall pterosaur, the horizon would be eight kilometers away, a journey Quetzalcoatlus would have been able to make in under eight minutes. Eight minutes of aerobic effort seems quite doable, so we’re still okay so far.

Interestingly, over the course of the Mesozoic Era pterosaurs became increasingly efficient flyers, except azhdarchids. Once the azhdarchid lineage appeared, it became less efficient over time until the end of the Cretaceous, when it produced its largest and least efficient members. This implies that flying must have been less important to Quetzalcoatlus and Hatzegopteryx than basically any other pterosaur, indicating that they probably spent proportionally more time on the ground. [5]

Now to address the question of whether Hatzegopteryx could have brought the Tethyshadros carcass with it to the island. As a disclaimer, I’m not an avionics expert and am making some very broad assumptions here. Quetzalcoatlus’s wing loading was the highest of any known flight-capable animal, at an estimated 224 Newtons per meter squared. The animal with the highest wing loading today, the Thick-Billed Murre (which looks like a penguin that flies, in exactly as unlikely a fashion as that sounds), has a wing loading of 184 Newtons per meter squared. It’s so heavy, the better for swimming and diving, that it’s only able to carry a single fish at a time while flying. This is unusual; most other seabirds that dive for fish, such as puffins, are less specialized swimmers and can fly lots of fish stored their beak and crop back to their nests.

The Thick-Billed Murre weighs about one kilogram, and an example of its prey, a capelin, weighs 50 grams, or five percent of the murre’s body weight. Since Quetzalcoatlus’s wing loading was 22 percent higher than the murre’s, I’ll generously estimate that it could carry four percent of its body weight (likely an overestimate due to the enormous size difference–physics doesn’t scale linearly!), which would be 10 kilograms for a 250 kilogram pterosaur. This is probably an overestimate for Quetzalcoatlus and almost certainly an overestimate for what Hatzegopteryx could carry, and it’s only half of what the show’s Tethyshadros carcass is stated to weigh.

So in conclusion, that baby hadrosaur would have been easy for Hatzegopteryx to pluck from the ground, but it would probably not have been able to lift it into the air. And even if it were carrying only a 10-kilogram weight, Hatzegopteryx would have been just able to go from island to island on its own, so that extra weight may have made such a journey impossible.

Could Quetzalcoatlus challenge T. rex?

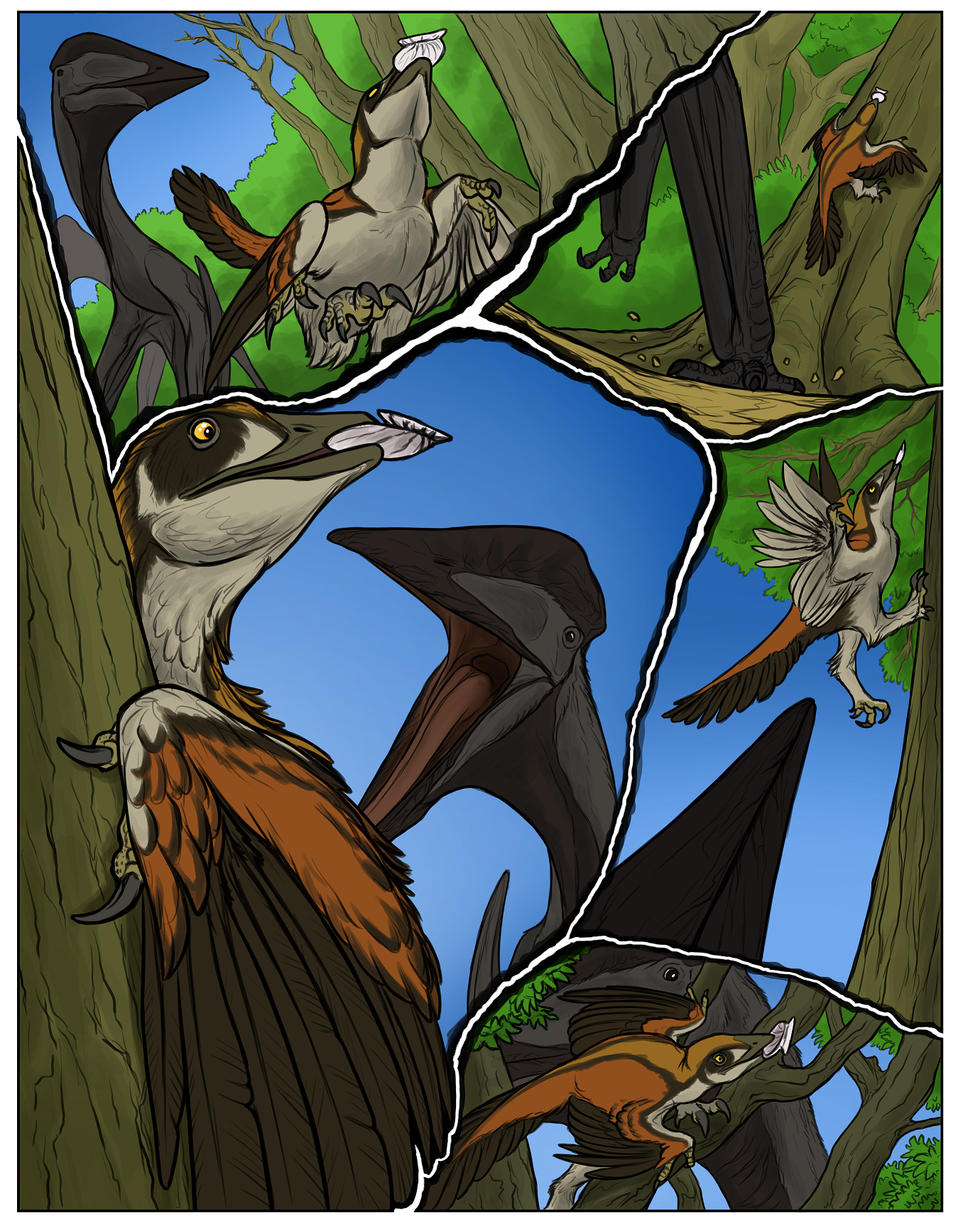

The other major scene that puts azhdarchids on a pedestal is in the last episode, “North America”. A giant Alamosaurus, an 80-tonne sauropod, is shown dying of old age on the beach, and the enormous carcass soon attracts diverse scavengers.

The first to show up are unnamed troodontids, soon followed by Tyrannosaurus. But the big predator only gets to eat peacefully for a few seconds before two Quetzalcoatlus show up and drive him off. Could this have happened this way?

First of all, were Quetzalcoatlus social and cooperative? This is a question that applies to Hatzegopteryx as well. While the flamingo-like Pterod’austro is known to have occurred in large cooperative colonies, it was only distantly related to the giant azhdarchids and therefore not a representative model of behavior. Specimens of Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni, a much smaller species closely related to the giant Quetzalcoatlus northropi, were found in a group of three adults buried together, indicating a small-group level of sociatity. This doesn’t necessarily mean Q. northropi was social; as an example of differing habits between species of the same genus, lions, Panthera leo, are highly social while tigers, Panthera tigris, are anti-social. That said, it is definitely possible that Q. northropi and Hatzegopteryx could have cooperated in small groups as they’re shown doing on screen.

But would they have challeneged an adult Tyrannosaurus over a prize? The closest modern analogue (though at a much less epic scale) would probably be vultures challenging cheetahs and hyenas. The very common White-Backed Vulture weighs up to seven kilograms, while cheetahs and spotted hyenas both can reach 64 kilograms, nine times the vulture’s weight. Vultures are known to drive cheetahs off of carcasses and to hold their own against hyenas, but they do it in mobs of dozens of birds, not just two.

Furthermore, the weight difference between Quetzalcoatlus and Tyrannosaurus was twice as extreme–Tyrannosaurus commonly could reach nine tonnes, compared to 250 kilograms for the pterosaur. Thus, you would think that Quetzalcoatlus would need even more overwhelming numbers to imtimidate such a large predator.

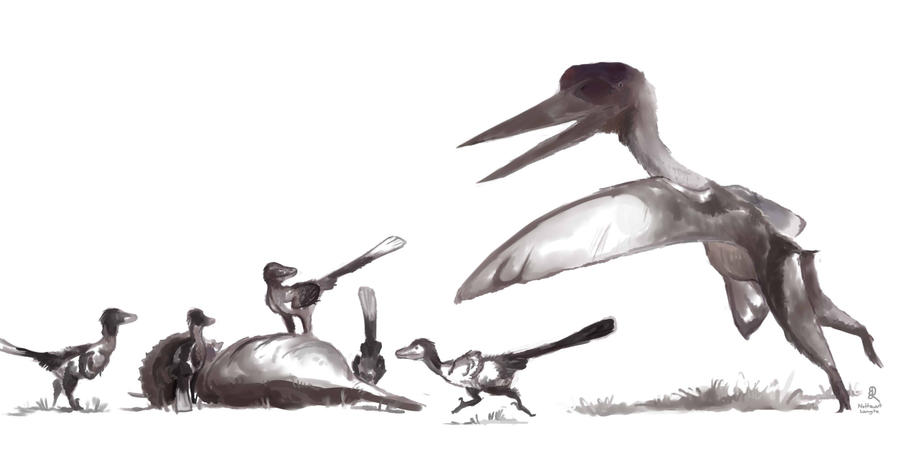

This is what more likely would have happened if the two pterosaurs had insisted on a confrontation:

What I think is the major flaw in this scene, however, is not the recklessness of the azhdarchids, but the small number of animals on the scene. While all continents other than Africa are today quite lacking in large animal biomass, this is a recent and unusual situation, caused by the end of the last Ice Age and overhunting and habitat destruction by prehistoric and modern humans. Throughout most of Earth’s history, in most places, Africa’s biodiversity was the rule rather than the exception. Also, though animal density in North America today is pretty low, carcasses are hotspots that attract hundreds of predators and scavengers, especially ones that can fly.

While dinosaurs and pterosaurs, being much larger-bodied than today’s megafauna, would have had correspondingly lower population sizes, the kill site in the show still seems quite the under-attended party.

Could azhdarchids fly just hours after hatching?

The last scene we’ll look at in this post is from the “Swamps” episode, in which unnamed azhdarchid flaplings flap for their lives to avoid being eaten by Shamosuchus, a large alligator-like predator. (The character model used for the azhdarchid flaplings is the same as the one used to represent unnamed pterosaur adults in the “Freshwater” episode of Prehistoric Planet 1.) This is another dramatic reenactment of a Naish and Witton paper, this time from 2021, that examined the flight-worthiness of flaplings, building on previous research describing the anatomy of those flaplings from 2019. Pterosaur remains, especially those of eggs, embryos, and hatchlings, have historically been exceedingly rare finds, since the eggs are soft-shelled and the skeletons are so delicate. However, in the last twenty years there have been a few big discoveries of hundreds of eggs and hatchlings preserved in a nesting location, and only now are scientists finally catching up in describing them all.

Today superprecociality, or the ability to fend for oneself shortly after birth, is very rare in flying animals. Most birds are born blind and unfeathered, and only fledge after a period of considerable parental involvement; some, such as chickens and ducks, are able to run or swim shortly after hatching, but can’t fly until later. As a counter-example, the megapodes, Oceanian birds in the chicken family, are born with full wing feathers and can fly shortly after hatching (which is necessary because their fathers tend to attack them for messing up the beautiful nest-mound he built). However, this adaptation is probably fairly recent, as no other fowl exhibit it, and unusual for flying animals, as this one family is the only example. Bats are also helpless at birth, with a single enormous pup born to each mother which breastfeeds while it grows its wings to flight-worthy proportions. Therefore, until the discovery of pterosaur flapling fossils, scientists assumed that pterosaurs would have needed to invest some level of parental care, at minimum protection from predators, if not feeding, to keep their ground-bound offspring alive.

However, the pterosaur embryos and hatchlings unearthed displayed surprisingly adult-like proportions and precocious amounts of limb ossification (hardening of the infant cartilaginous skeleton into bone), specifically in the wings and legs. Their keel (breastbone), to which flight muscles attached, was not ossified, but since it’s only in tension rather than bending, cartilage would have been able to withstand the forces necessary to fly. [6]

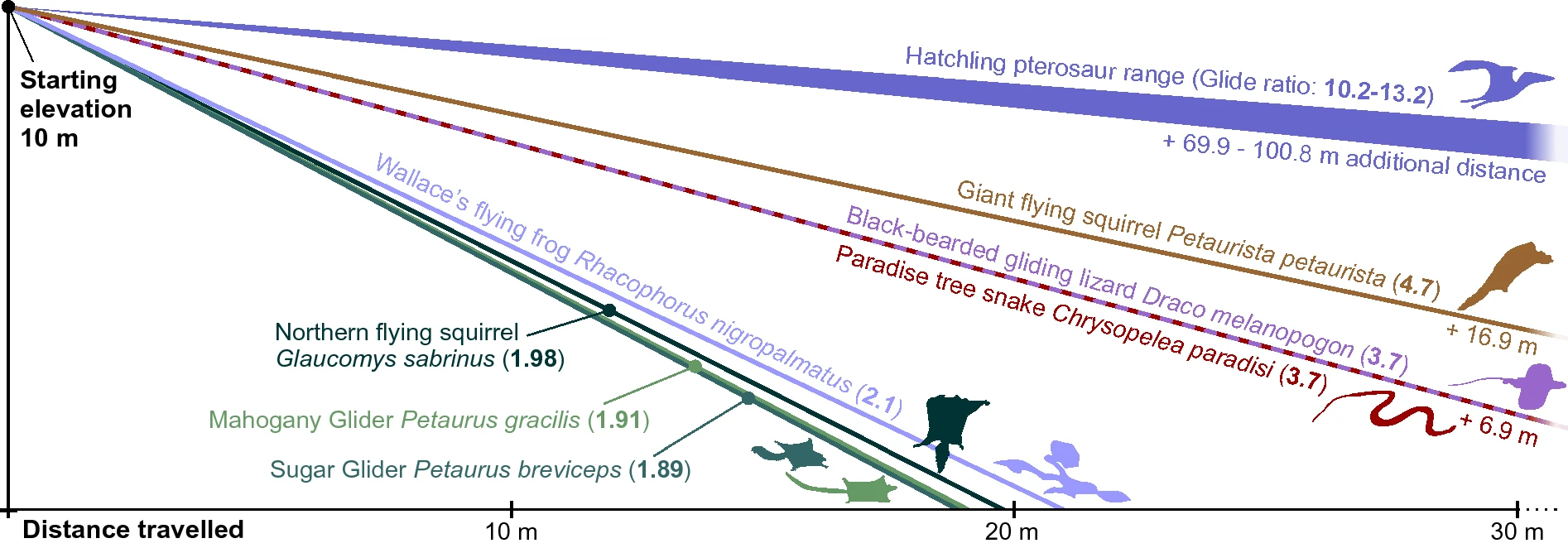

Subsequent research investigated the strength of the flaplings’ wing bones and found that they were actually proportionally stronger than those of the adults, indicating not only flightworthiness but also that they would have been more maneuverable. They also had a smaller aspect ratio (broader wings) than adults, suggesting that they would have been better suited to short flights in cluttered environments like forests, rather than longer flights in open habitat like the adults. The same study modeled the flaplings’ aerodynamic performance and found them to be significantly better gliders than any modern gliding animal, with a glide ratio more similar to powered-flighted animals. [7]

The idea of flaplings having to cross a predator-infested body of water probably comes from the real-life maiden voyage of albatross chicks from the island of Laysan. Black-footed and Laysan Albatross fledglings, having been recently abandoned by their parents, must leave the desert island to seek food on the open ocean, but tiger sharks anticipate the fledging season and patrol the waters in great numbers, making any near-shore splashdown almost certain death. For basically a live-action version of the flaplings-versus-Shamosuchus scene, check out the first and second episode of Our Planet II on Netflix, also narrated by Sir David Attenborough.

The last thing the flapling is shown doing is swimming using a butterfly stroke. This is something I’ve previously mentioned bats are capable of, so it stands to reason that pterosaurs would have swum this way as well.

Conclusion

Since two of the scientific advisors are pterosaur specialists, it makes sense that the portrayals of pterosaurs in the show would emphasize their impressive size and capabilities. While some of the more extreme feats of strength and bravery are probably exaggerated, the overall depiction of these awe-inspiring animals is pretty accurate, and it’s kind of refreshing to have a protagonist other than Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus for once.

References

[1] Naish, D., & Witton, M. P. (2017, January 18). Neck biomechanics indicate that giant Transylvanian azhdarchid pterosaurs were short-necked arch predators. PeerJ, 5, e2908. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2908

[2] Gigantic flying pterosaurs had spoked vertebrae to support their “ridiculously long” necks. (2021, April 14). EurekAlert! https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/689108

[3] Chatterjee, S., & Templin, R. J. (2004). Posture, locomotion, and paleoecology of pterosaurs. Posture, Locomotion, and Paleoecology of Pterosaurs. https://doi.org/10.1130/0-8137-2376-0.1

[4] Goto, Y., Yoda, K., Weimerskirch, H., & Sato, K. (2022, March). How did extinct giant birds and pterosaurs fly? A comprehensive modeling approach to evaluate soaring performance. PNAS Nexus, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac023

[5] Benton, M. J. (2020, October 28). Pterosaurs increased their flight efficiency over time – new evidence for long-term evolution. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/pterosaurs-increased-their-flight-efficiency-over-time-new-evidence-for-long-term-evolution-148949

[6] Unwin, D. M., & Deeming, D. C. (2019, June 12). Prenatal development in pterosaurs and its implications for their postnatal locomotory ability. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 286(1904), 20190409. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.0409

[7] Naish, D., Witton, M. P., & Martin-Silverstone, E. (2021, July 22). Powered flight in hatchling pterosaurs: evidence from wing form and bone strength. Scientific Reports, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92499-z

Image Credits

Shoebill Tethyshadros Hatzegopteryx Spoked vertebra Penguin mouth Kori Bustard Eta glider Quetzalcoatlus and dromaeosaurs Thick-billed Murre Hatzegopteryx mating dance Alamosaurus Quetzalcoatlus and Ornithomimus Hyenas and vultures Pterosaurs vs T. rex Ravens and wolves Flapling Brushturkey chick