Last time I was in Washington, D.C. in 2019, I visited the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History and was disappointed to find out that their dinosaur exhibit was under construction. I recently went back to visit family and got to see the new (ish–I missed the opening in 2019 by just a couple months) Fossil Hall. Since it’s a publicly funded museum, it’s free to visit, something I didn’t recall from last time that was a pleasant surprise.

The Fossil Hall is arranged reverse chronologically, with the most recent fossils near the entrance and the most ancient ones in the rear. Probably, this decision was made because mounted mammoth and ground sloth skeletons are much more charismatic than Ediacaran frond imprints, but I’m going to describe the exhibits from most ancient to most recent.

In the very back is the fossil prep lab, where you can see museum employees working to excavate, preserve, and restore specimens. The main event there was a Gorgosaurus (smaller relative of Tyrannosaurus) skeleton that had been encased in plaster awhile ago to display it, an outdated technique. (Plaster casts are still used to protect recently-excavated fossils in transit, but the plaster goes around the whole block of rock, and can therefore be removed fairly easily, rather than around the bones themselves.) Now, to restore it, the worker has to pick the bones out very carefully, one by one!

Right across from the lab is the Stegosaurus stenops holotype, or the first specimen ever scientifically described, which defines what it means to be Stegosaurus stenops. When other Stegosaurus fossils are described, they’re compared to the literature on this one, and if they are sufficiently different they could be declared a new species.

I think this is the most important holotype I’ve ever seen. Stegosaurus was one of the dinosaurs from the early days of paleontology, and has gone through numerous revisions in its interpretation over the century it’s been known. Scientists used to think the plates might have formed a turtle-like shell, explaining its name of “roof reptile”. It was also impressive to me that this specimen is so fragmented–every plate had to be pieced back together like a jigsaw puzzle!

There’s also a corner of the museum back here with information on the process of evolution. This example, using 3 million year old scallop fossils and modern ones, does a good job showing how small within-species differences can become exaggerated over time until different species arise. It’s a cool, and very clear, real-life example using real fossils, something I have not seen before.

Ediacaran Through Devonian Exhibits

Ediacaran through Early Devonian Case

To represent the Ediacaran, Cambrian, and Ordovician Periods, there was a single large display case jam-packed with fossils, casts (replicas of particular fossils), and information. They had lots of famous fossils from the Burgess Shale in Canada, such as original material of the early chordate Pikaia and the spiky, scaled slug Wiwaxia. It was a bit of a whirlwind tour of such a long time span, but the fossils are top notch and the information useful.

The scaled oddity Wiwaxia (number 10).

To represent the Silurian and Early Devonian periods, there was another fossil display case.

Some sea scorpions and early land plant fossils from the Silurian Period. As I’ve mentioned before, 98 percent of sea scorpion material known belong to the one genus Eurypterus. Cute little guys!

A cross-section of Prototaxites, the tree-sized fungus from the Silurian, showing its treelike growth rings.

The armored fish Bothriolepis. The information here that its relative Dunkleosteus could grow up to nine meters long is now out of date, in favor of an updated estimate of only five meters, but only as of a few months ago! I don’t hold it against them.

A selection of the different types of fish present in the Devonian Period. They are all casts though. Number 6: Cladodus (shark) tooth, 7: Apateacanthus (spiny shark) spine, 8: Gogonasus (lobe-finned fish) skull. I’m not sure where on the body number 7 would have gone. Perhaps they should have a drawing?

Overall, the Ediacaran through early Devonian exhibit is an 8 out of 10. Informative and full of good fossils but too compact.

Cambrian through Devonian diorama

There was also a big diorama showing the progress of plant life onto land. I loved these dioramas–starting here, there was one for every period. They were so cute and informative!

A diorama showing the progress of plants from water to land between the Cambrian and the Devonian Periods. The large spears in the second panel are Prototaxites, whose cross-section and description were provided above.

By the Late Devonian, land plants had diversified into something resembling a forest.

My only issue with the dioramas was that the horrible glare made it hard to see details and get good pictures. Haven’t they ever heard of anti-glare museum glass? 9 out of 10.

Late Devonian cases

Finally, there was another display covering just the Late Devonian, when vertebrates made the transition from water to land.

A cast of Acanthostega, a famous “-stega” (early tetrapod) and a fossil of Eusthenopteron, a lobe-finned fish.

This progression makes it look like the number of fingers decreased linearly until we arrived at the ‘right’ number of fingers and were finally rewarded with land-worthiness. In reality, the number of fingers in early tetrapods seemed to be random and didn’t greatly affect their fitness. It’s just coincidence that we ended up with five.

A big bronze statue of Orobot, a robot made based on the early tetrapod Orobates, used to figure out what gait Orobates would have used while walking and what sort tracks it would have made. Orobates lived in the Early Permian, but the statue was nearest to the Late Devonian and Carboniferous exhibits. There was no information at all near this statue, I just happened to know what it was.

In addition to this, there was a sign discussing the challenges of moving from an aquatic to fully terrestrial lifestyle, including supporting one’s body weight, breathing air, regulating one’s own moisture level, and laying waterproof eggs, but I didn’t take a picture of it. With this sign, this exhibit is a 6 out of 10: kind of scatterbrained and with some missing and misleading information.

Carboniferous Exhibit

As we move forward in time, the exhibits get more extensive. This is both due to the higher abundance of fossil material the closer you get to the present, and to the fact that large charismatic animals and plants are more interesting to most museum-goers than tiny sea slugs.

A big tree trunk from so long ago, back when wood was a hot new invention and no animals, microbes, or fungi had figured out how to digest it yet. Unfortunately, this one is labeled Callixylon, which is a junior synonym of Archaeopteris (meaning “ancient fern”, not to be confused with Archaeopteryx, meaning “ancient feather”).

A really impressive fossil skeleton of Seymouria, a reptile-like amphibian from the Early Permian. This was displayed right next to the tree trunk rather than near the other Permian fossils, for some reason.

Some examples of plants from the Carboniferous, including horsetails and ferns that grew much larger than they do today, since conifers and flowering plants didn’t exist yet.

Some more Carboniferous plants, showing the cool textures of lycopsids, or scale trees. These trees make up a large portion of the coal we use today.

A diagram showing how different families of plants are related to one another. I find this bubble type of chart much easier to digest than a tree chart. The structure makes the difference between monophyletic, paraphyletic, and polyphyletic groups obvious.

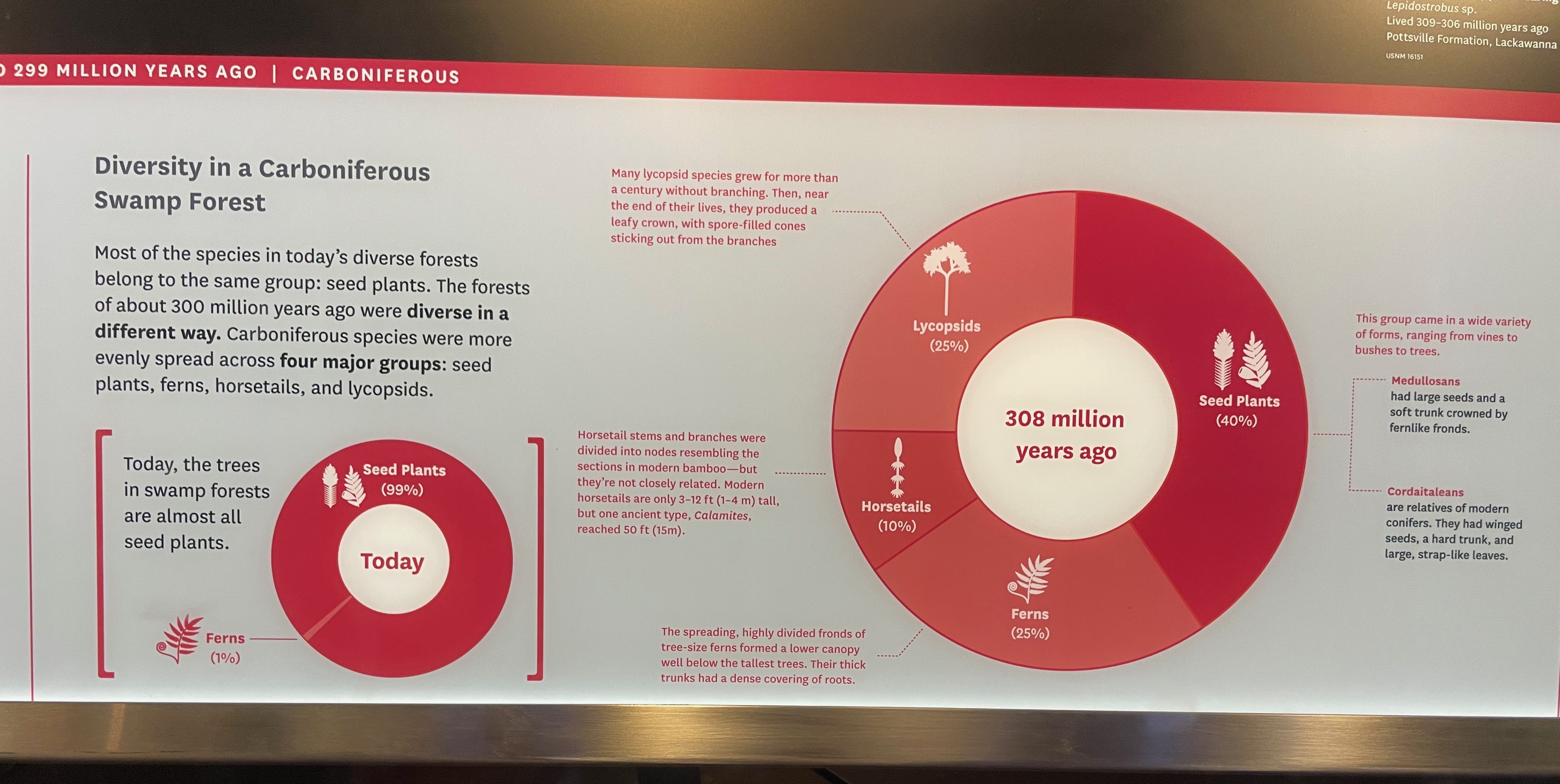

A diagram explaining how the makeup of Carboniferous forests differed from today’s. Very well said and interesting!

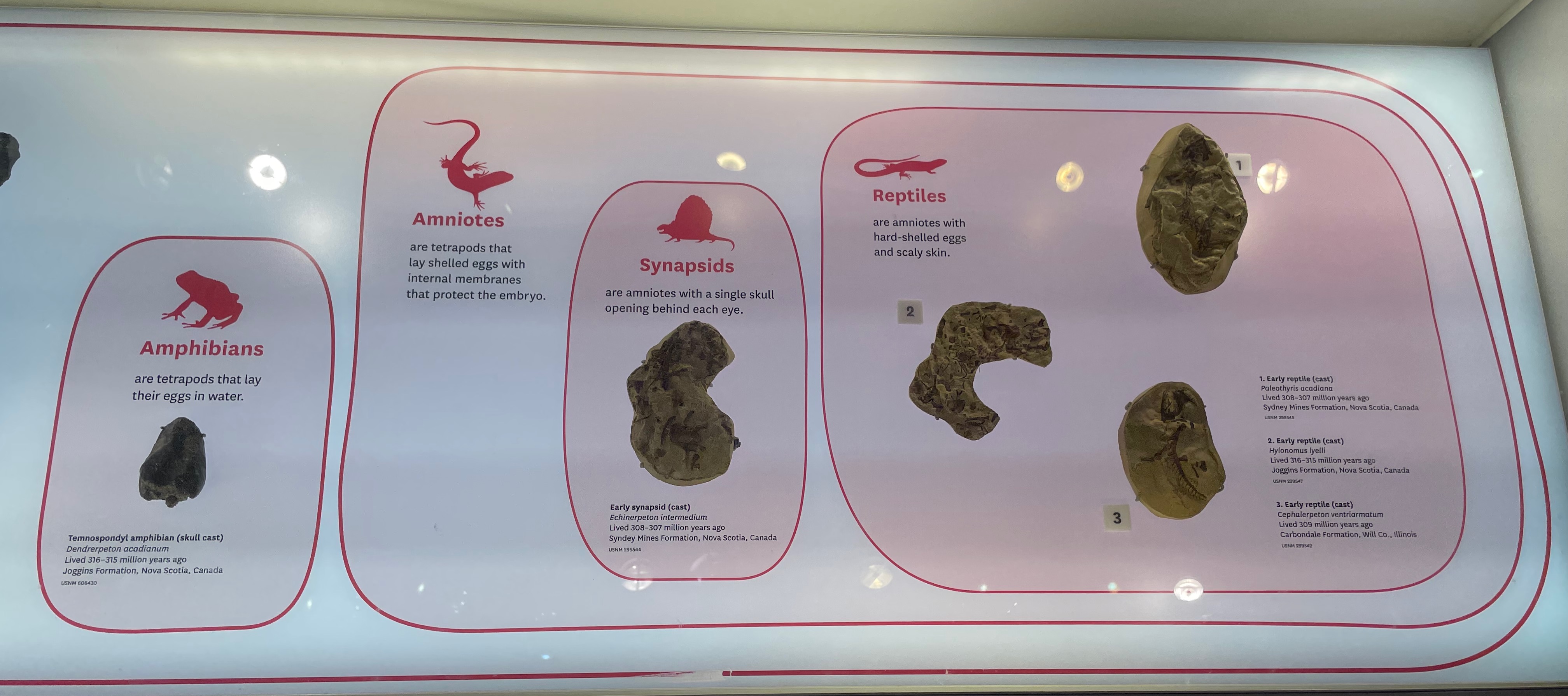

Another bubble diagram showing how amphibians, reptiles, and synapsids (mammal relatives) are related to one another, with casts of little skeletons. The additional info below this explains the importance of the amniotic (waterproof) egg in reducing animals’ dependence on bodies of water, but it doesn’t state that mammals are synapsids.

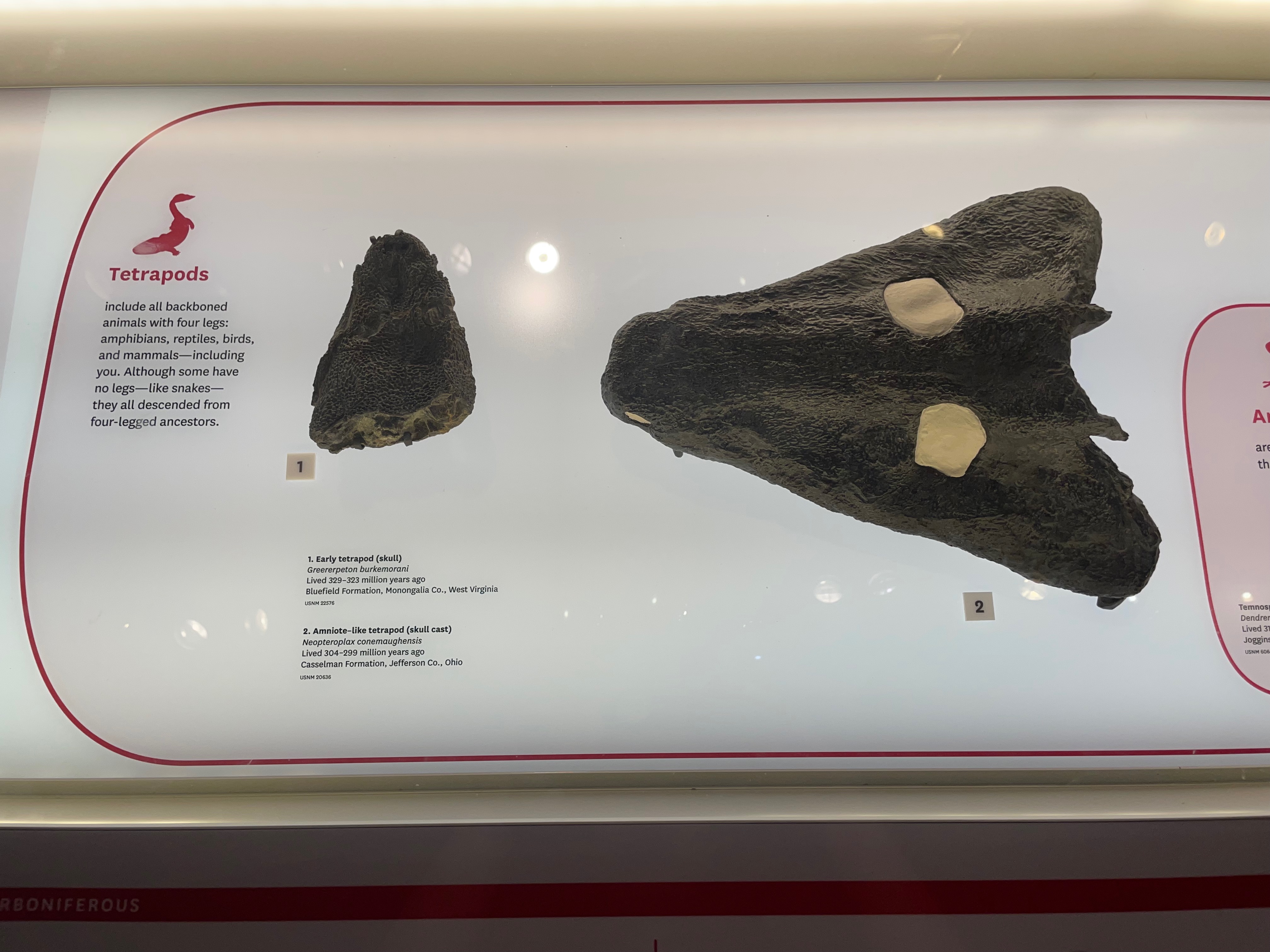

The bubble diagram continues to the left to describe tetrapods in general, and to explain how even though snakes have no legs they are still tetrapods since they descended from four-legged ancestors, a good fact to point out. This side of the case includes an early tetrapod, Greerpeton (the only real fossil in this case), and a large reptile-like tetrapod, Neopteroplax. However, the reptile-like tetrapod is probably in the wrong place in the bubble diagram. As a reptiliomorph, it should be in a bubble including itself and amniotes and excluding amphibians, but outside the amniote bubble. However, its taxonomy isn’t certain, so I won’t deduct too many points for this.

Here’s a to-scale bronze statue of the famous giant millipede, Arthropleura, along with a cast of its trackway, to show how it would have created those marks in the mud. I think this is a cool way to present it. Plus, this bronze statue isn’t in a case, unlike the Orobot statue, which is fun since you get to touch it (and you can see which parts people like to touch based on the level of polish).

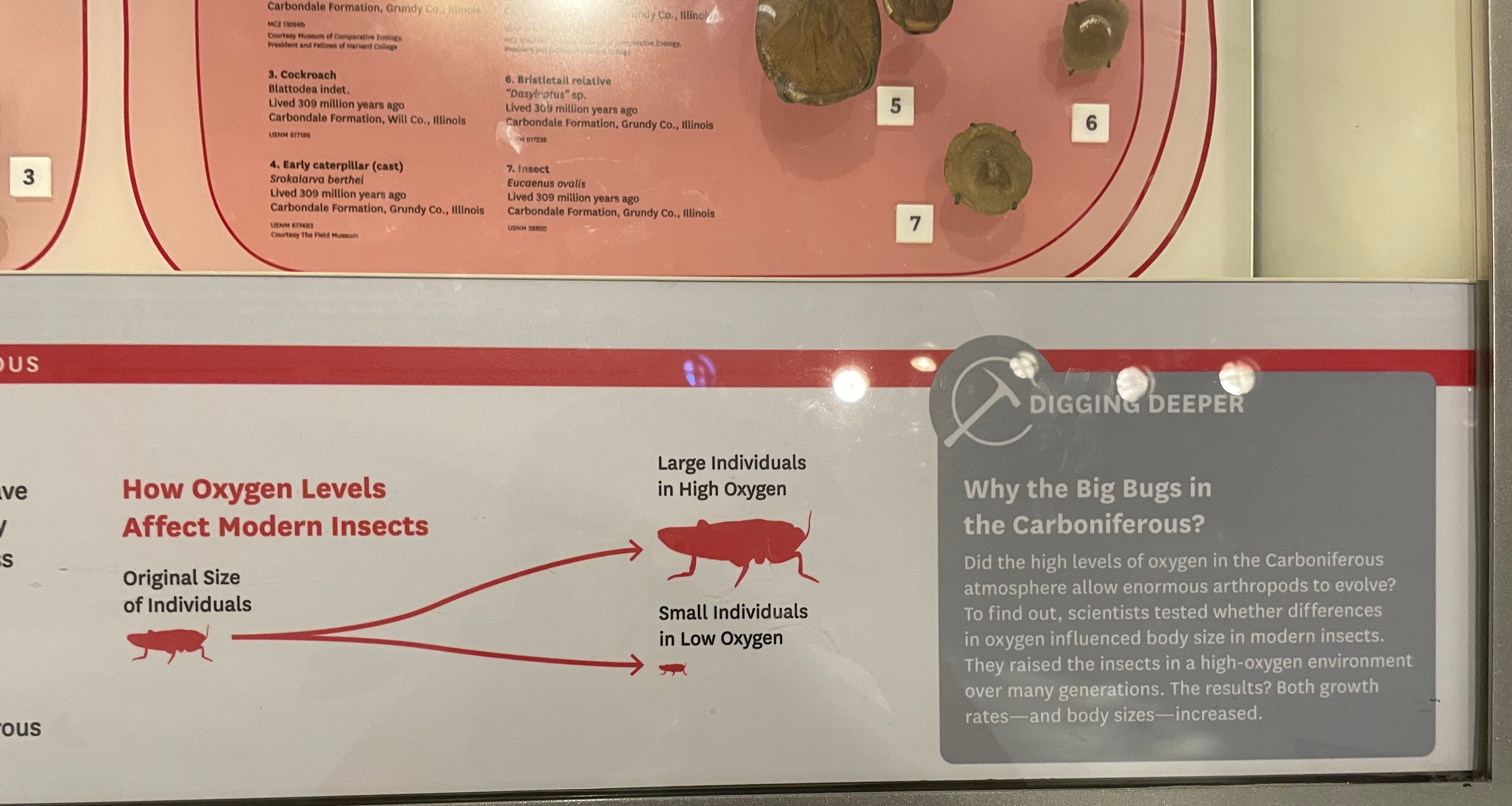

A section of a display case containing insect fossils from the Carboniferous. The “Digging Deeper” overlays that occur throughout the museum’s signage highlight a particular study, helping to explain how we know what we know. I think it’s a good idea to include these, but in this particular case, oxygen levels don’t tell the whole story about the big bugs in the Carboniferous. Some of the largest bugs occurred before the oxygen level spike, probably due to lack of competition from tetrapods in land-based niches.

On a side note, I love how the cockroach family’s scientific name is Blattodea. It just sounds gross.

Overall, I would rate the Carboniferous section 7 out of 10. There are a few minor issues with the information, but overall the museum put a lot of effort into this time period that’s often less loved than everything that comes later.

Permian Exhibit

The Permian Period was the first time charismatic land predators existed, such as Dimetrodon the fin-backed mammal relative and saber-toothed gorgonopsids. Accordingly, this exhibit mostly focuses on these large animals and their prey. Also, as we move forward in time and larger animals are on display, a higher proportion of them are real fossils or composites (fragmentary fossils completed with cast pieces) rather than full casts.

Here’s a big, toothy Dimetrodon in a semi-sprawling stance, feeding at the carcass of a smaller carnivorous synapsid (it was labeled but I forgot to take a picture of the label). These signs point out that despite being popularly associated with dinosaurs, Dimetrodon was a mammal relative.

This is the skull of Orthacanthus, a big shark with a unicorn-like horn and two-pronged teeth. I’d seen pictures of unicorn sharks before, but didn’t picture them being this big!

This is the big amphibian Eryops, which had the most heavily built skeleton of any temnospondyl. Like most amphibians, it was a predator, but it would have also been preyed on by bigger carnivores.

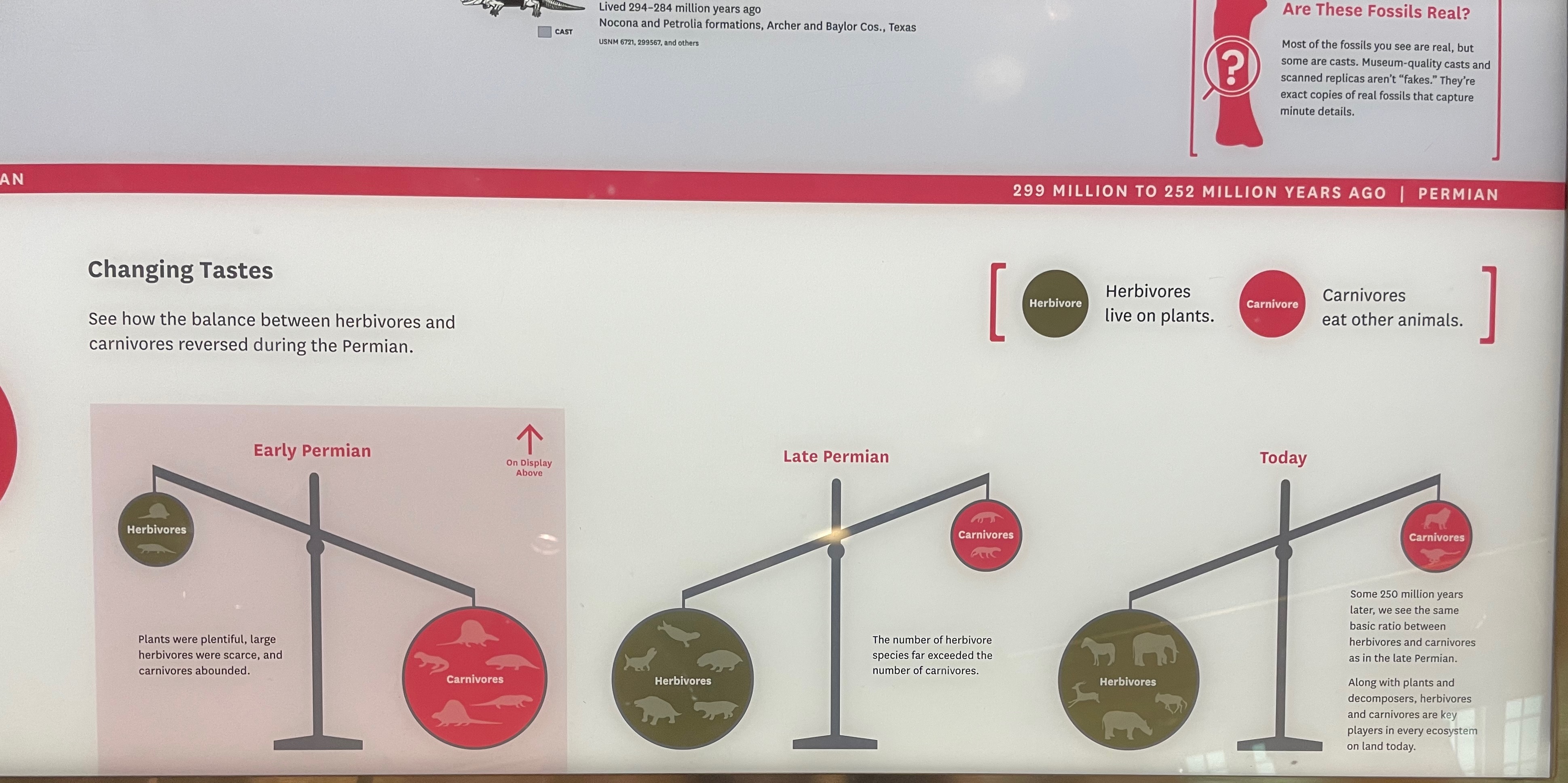

This diagram highlights the difference in predator-prey ratios between Early Permian, Late Permian, and modern ecosystems. There was a much higher density of carnivores, probably due to the metabolic efficiency of animals back then–all of them were cold-blooded and slow-moving like alligators, and could therefore subsist on little food relative to most of today’s predators, allowing the ecosystem to support more of them. This is a cool detail to include!

A cute little diorama showing some Early Permian megafauna, including Dimetrodon, the fish-eating Secodontosaurus, the fin-backed herbivore Edaphosaurus (of which the museum did have a full mounted skeleton, but I failed to get a good picture because of glare), and Eryops.

Moving on to the Late Permian, we have the skeleton of the small burrowing dicynodont (mammal relative) Diictodon. It looks pretty big for a digger! I always imagined it to be smaller. In the foreground are Glossopteris, an early seed plant, and in the background are the skulls of the big pareiasaur (para-reptile) Bradysaurus (far left), the big dicynodont Aulacephalodon (far right), and the medium-sized carnivorous therocephalian Proalopecopsis (midground). I tried to take a better picture of the big skulls from the other side of the case, but the glare made the pictures unusable.

The skeleton of big dicynodont Platypodosaurus. It was an herbivore despite the intimidating fangs–in fact, those fangs were its only teeth, and it relied on a beak to crop plants, like a tortoise. That big protruding cheekbone would have anchored strong biting muscles.

10 out of 10, wouldn’t change anything except the glass glare.

Triassic Exhibit

We’ve made it to the Mesozoic!

Triassic Seas

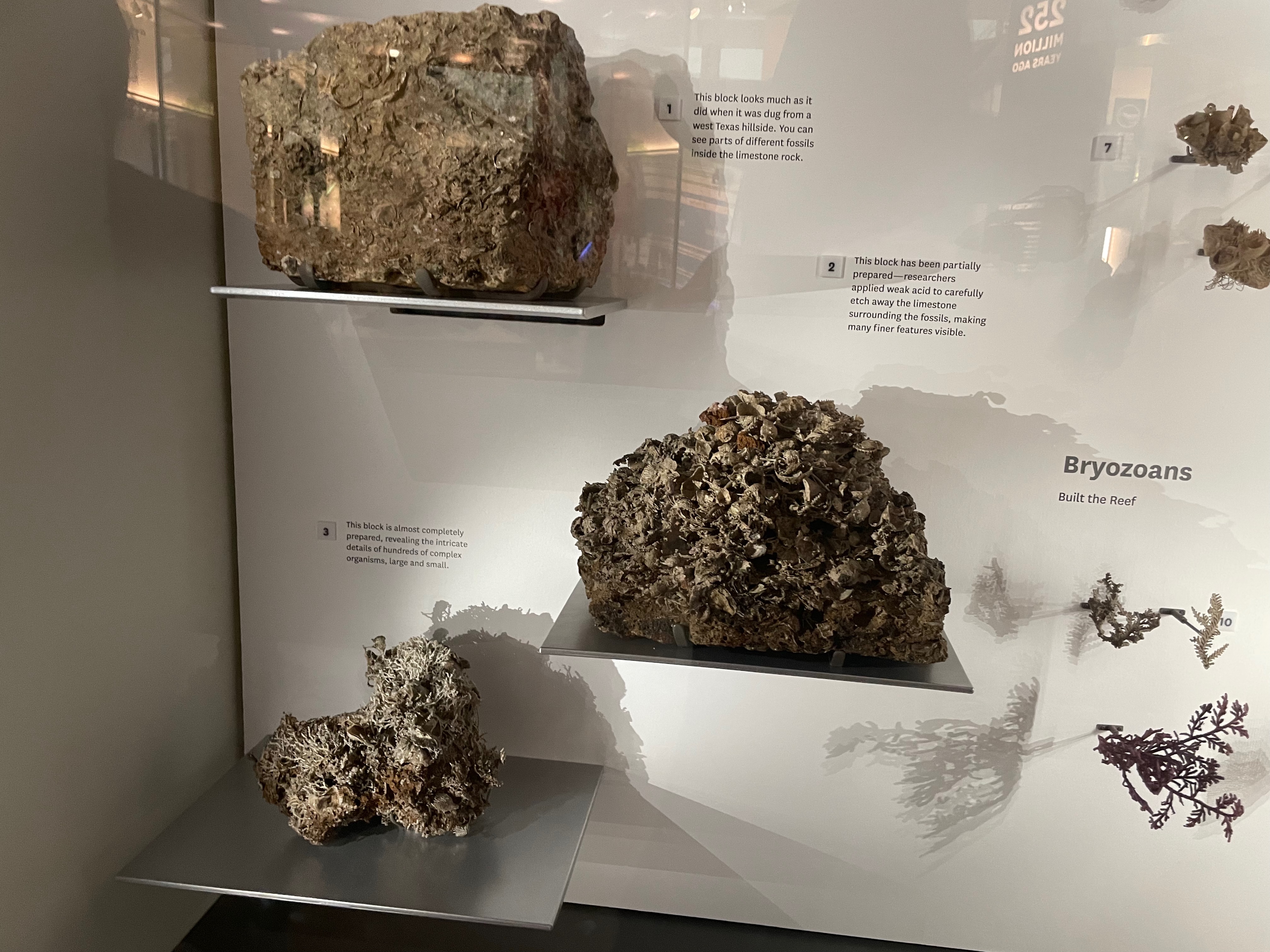

These specimens show the progression of fossil preparation using acid etching. The top block is how the fossil is excavated from the ground, and then using multiple applications of weak acid, the organisms inside are revealed. In particular, these fossils are bryozoans, some of the reef builders from the Triassic, before modern coral had evolved. Other reefs existed before this as well, made from rudist clams, sponges, and other types of ancient coral.

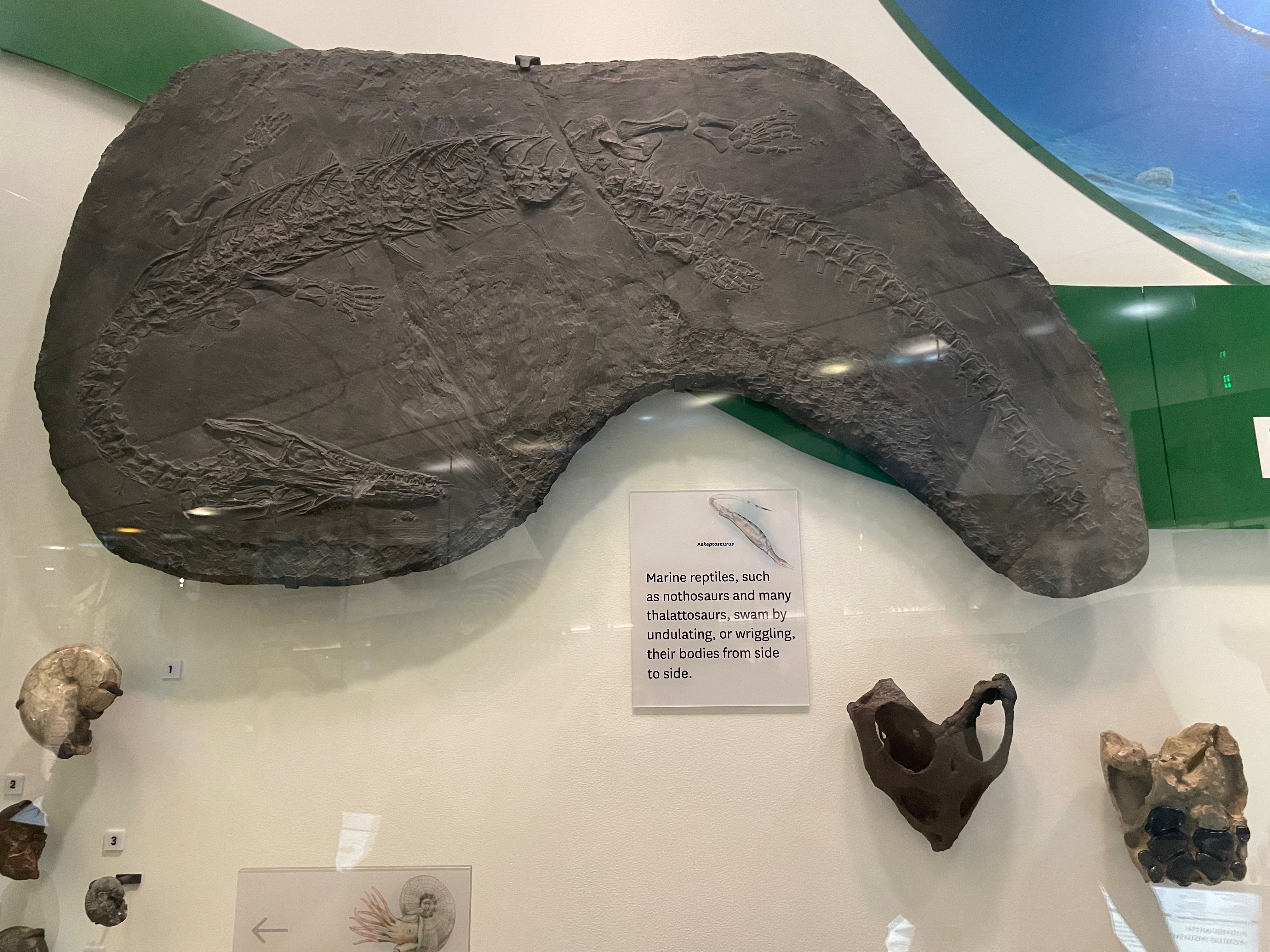

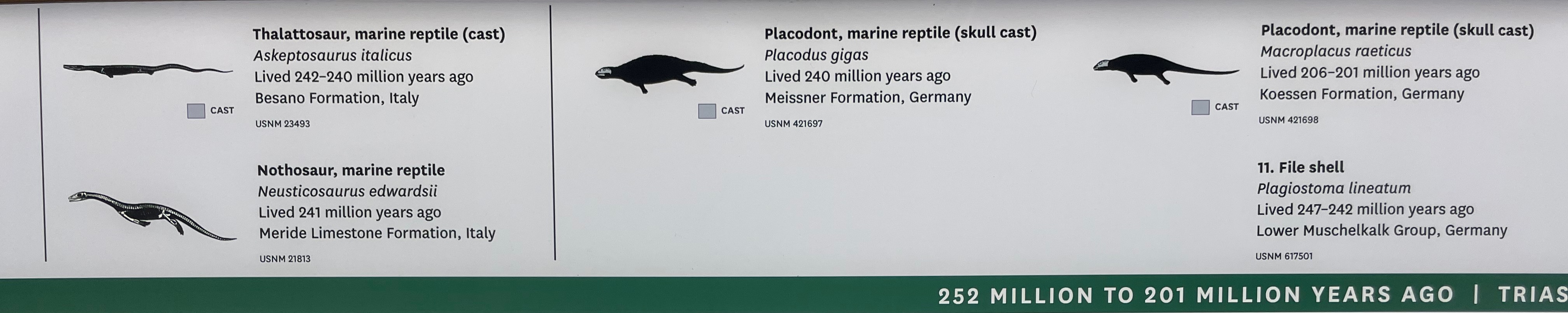

This skeleton cast belongs to the Triassic thalattosaur (seagoing reptile) Askeptosaurus. To the right of it are casts of placodont skulls (turtle mimics), and to the left are the shells of ammonites (shelly squid relatives), marine snails, and clam relatives from the Triassic.

Throughout the museum, there are small skeletal diagrams on the signage identifying the fossils like those above. However, it’s often hard to understand which skeletal refers to which specimen because the skeletals are shown in plain side view and all the same size, while the fossils are all twisted up and range from finger-sized to whale-sized. If I hadn’t told you, would you have been able to confidently identify the above seal-sized fossil as Askeptosaurus and not Neusticosaurus? But the latter is the size of a small lizard! One positive aspect of the skeletals is that it shows approximately what the animal would have looked like in life, which visitors might not be able to understand from a deformed or incomplete fossil. Maybe the best thing would be to number them like the smaller specimens, or to include a diagram of how the fossil itself looks in addition to the skeletal.

Triassic Land

This is Trilophosaurus, an archosauriform reptile. This guy is close to my heart because research on its bone histology (microscopic growth patterns) showed that it was close to warm-blooded, pushing back the origin of this feature in reptiles by many millions of years. It lent support to the hypotheses that endothermy is ancestral to archosauria (birds and crocs) and crocs secondarily returned to a cold-blooded lifestyle, and that proto-feathers might have been present on all kinds of early non-ornithodire (outside of dinosaurs and pterosaurs) archisauriformes. However, this particular mount… it looks like something’s wrong about the extension of that front leg.

This is a cast of Eoraptor, an early sauropodomorph (relative of long-necked dinosaurs). While I appreciate how fat they made him using the gastralia (belly ribs), there are a couple things wrong with this mount. While the signage below correctly identifies it as an omnivore, the sign nearest to it calls it a carnivore. And while the sign below says it had three claws on its five-fingered hands, which is correct, the cast very clearly only has three fingers in total. Strange… where’d those other four fingers run off to?

The centerpiece of the Triassic display is the mounted composite skeleton of Smilosuchus, an enormous phytosaur (croc mimic), complete with osteoderms (bone armor), gastralia, and chevrons (tail underside supports). It’s mounted in an odd crouching position rather than the belly sprawl that’s the resting posture of today’s crocs. Behind it, there’s a cast of the strange little armored swimming reptile Vancleavea, which I talked more about in my post on the Chinle formation, and in front of it are an early turtle shell, the skeleton of a small temnospondyl amphibian, and a cast of the very flat skull of a large temnospondyl amphibian.

By Smilosuchus’s side, there are a few small Triassic mammaliformes along with a sign describing the transition from a reptile-like three-boned jaw and one-boned ear to the mammalian one-boned jaw and three-boned ear. This distinction, while important for classifying fossils, is not something I think interests the average museum guest, yet seems to be highlighted in every museum. Why?

Here are two different cross-sections of the petrified conifer Agathoxylon, which was common in the Triassic, showing the transition toward the modern distribution of plant diversity. It’s so pretty–I want one as a coffee table!

The Triassic diorama features phytosaurs, a small pterosaur, large temnospondyls, a large dicynodont (holdovers from the Permian), and small theropod dinosaurs.

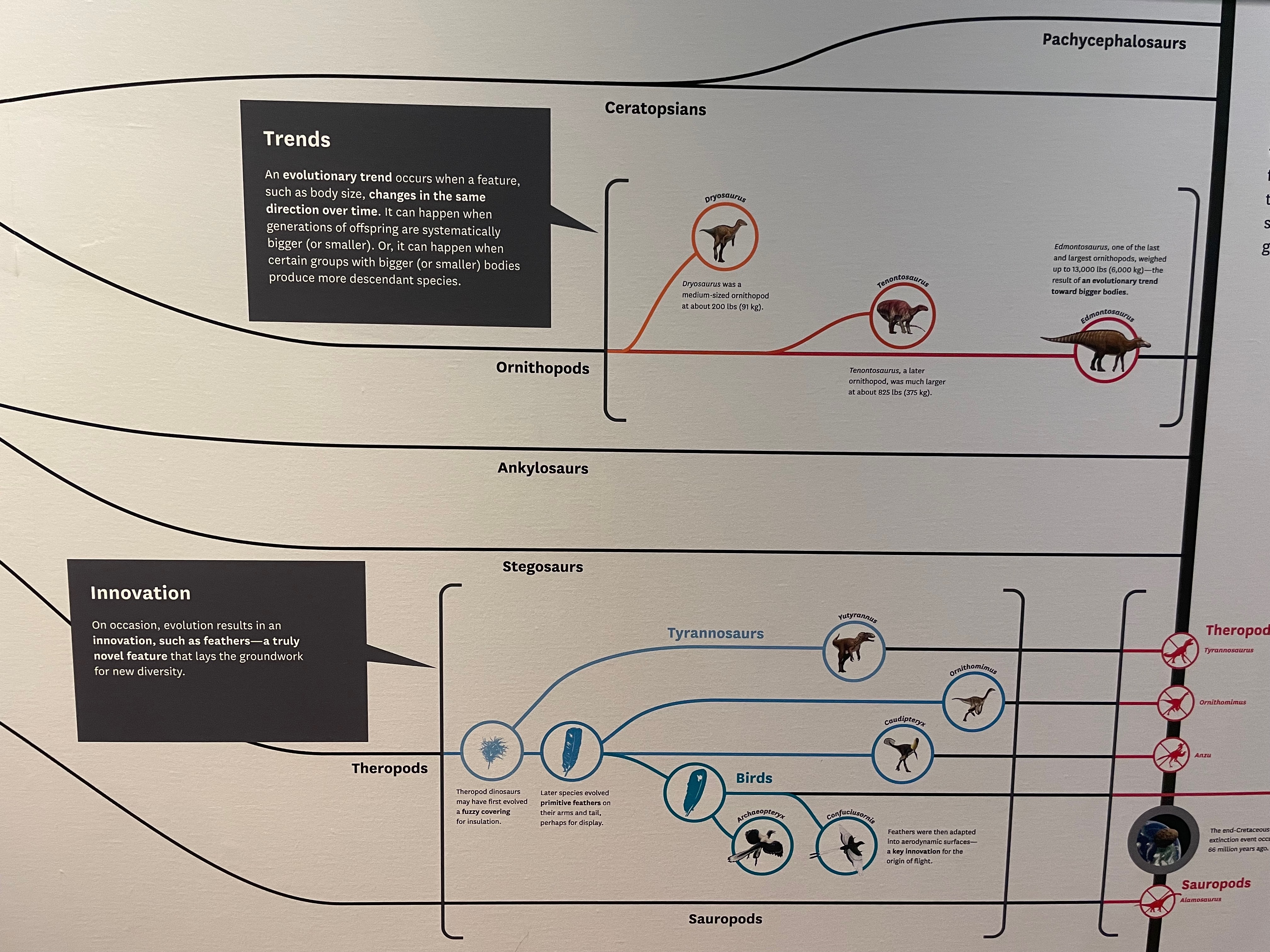

Just before entering the main dinosaur hall with Jurassic and Cretaceous dinosaurs, there’s a large poster depicting the dinosaur family tree and various important events and representative genera. Overall it does a good job showing how the various groups are related to one another, but there are a few details I would change. It doesn’t give examples of ceratopsian, pachycephalosaur, stegosaur, or ankylosaur genera, which would have been nice to have. It shows Tyrannosaurus as evolving from Yutyrannus and Anzu as evolving from Caudipteryx, when the more primitive form should actually be shown as a small branch off the main line in the same way that Archaeopteryx is shown. I’m not sure why they did this correctly in some places and not others–maybe to save space?

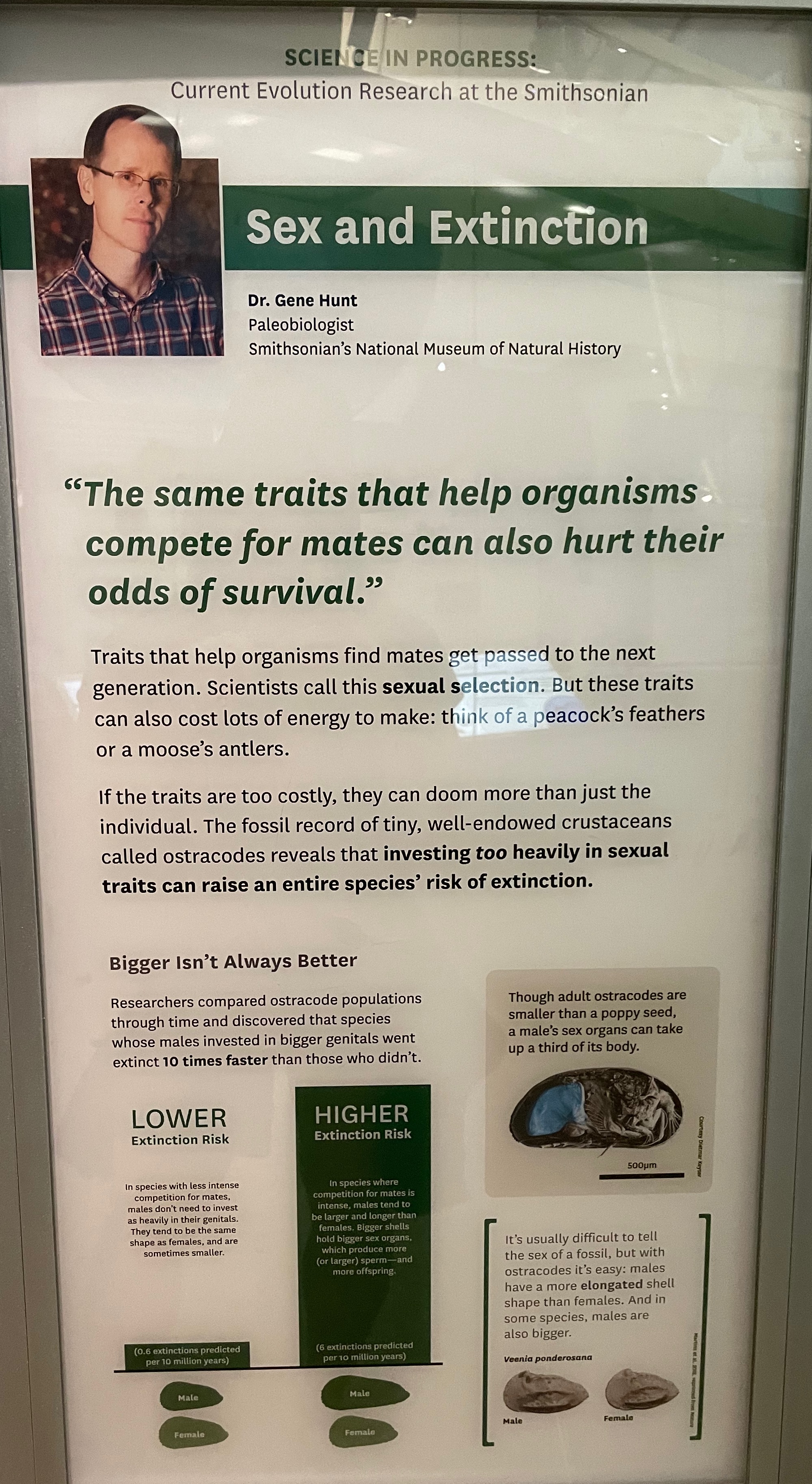

Directly to the right of the dinosaur tree is a somewhat unrelated but interesting poster about current research happening on fossils in the museum collection. This research found a correlation between the relative size of ostracods’ (tiny shrimp, also called ostracodes) genitals compared to their bodies, and extinction rate of species. While this is a neat finding, it has the potential to be misinterpreted as supporting the “evolving oneself into a corner” hypothesis that used to be a popular explanation of why animals with exaggerated sexual characteristics like the Irish elk went extinct, but is now thoroughly debunked. I think it would have been nice to have realized this possibility and added a note to clarify that it’s not the sexual characteristic itself that causes extinction on its own, but when conditions change those who spend more resources on those traits are less likely to survive.

Overall, I would rate the Triassic exhibit 7 out of 10. There are a few issues, but the fossils are stunning and the information provided is useful and comprehensive.

Jurassic Exhibit

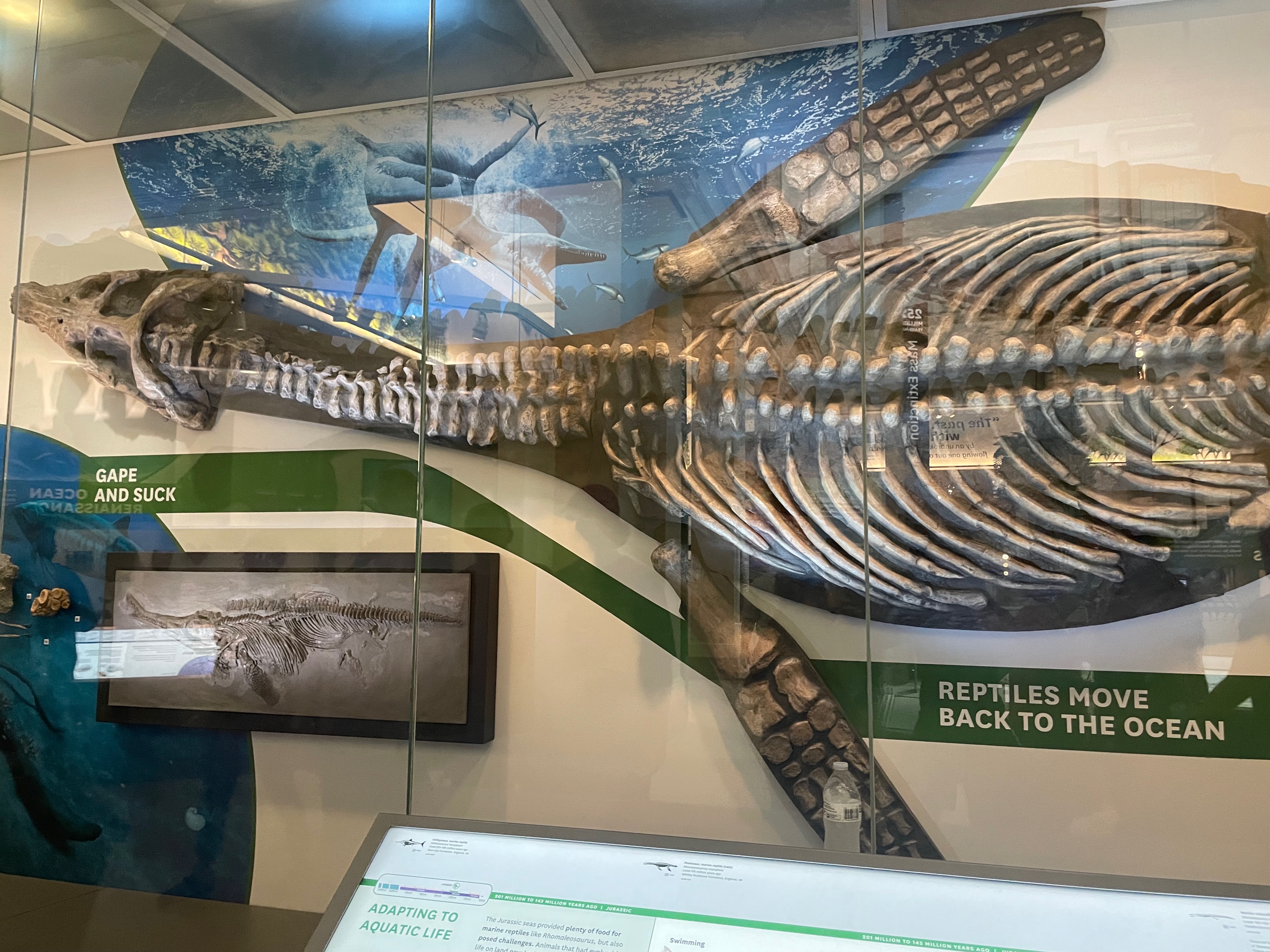

Jurassic Seas

Continuing along the hallway that contains Triassic marine reptiles leads one toward the Jurassic exhibit, starting with the diversification of additional marine reptiles. A huge cast of Rhomaleosaurus, a short-necked plesiosaur, dominates the wall.

“Gape and suck”–a bit of a questionable choice of words, in my opinion.

Next to the plesiosaur centerpiece there’s a real fossil of Steneosaurus, a dubious genus of teleosaurid (marine croc). This name has been used as a wastebasket taxon for a long time, but has not yet been cleaned up, which isn’t the museum’s fault! You can see a lot of its osteoderms, or bony back plates, scattered about the fossil. Since osteoderms grew in the skin and weren’t connected to the rest of the skeleton, they are not often preserved articulated, or in life position. Therefore, a lot of paleoart of ancient osteodermed animals is just guessing where on the body they might have gone!

A small sign near this fossil explains what osteoderms are, but misspells Steneosaurus as “Stenosaurus” only one of the few times it is written.

Here’s a fossil of Stenopterygius, the well-known little ichthyosaur that I’ve drawn a few times before. Look at all the finger bones!

There’s a sign underneath with a picture of an ichthyosaur, shark, and dolphin, explaining about convergent evolution. “Stiff, smooth bodies, tall dorsal fins, and strong tails allowed them all to be fast-swimming predators.” I think this is a nice thing to include, and it’s presented a lot more understandably than many convergent evolution posters and textbooks I’ve seen.

Jurassic Land

Finally, we’ve reached the dinosaurs! Here’s a mounted Stegosaurus skeleton defeating a mounted Ceratosaurus, a type of primitive medium-sized theropod named for the little horns on top of its skull. It’s currently unknown how Ceratosaurus coexisted with the other similarly sized predators Torvosaurus and Allosaurus, but they almost certainly niche partitioned somehow. Ceratosaurus was rare in its environment, while Allosaurus was abundant. Mounting this upside-down must have been a challenge!

Here’s a mounted adult and juvenile of Camptosaurus, a smallish, bipedal relative of the later “duck-billed dinosaurs”. Look at that enormous fourth trochanter, the blade of bone sticking out the back of the femur (upper leg bone). This was an attachment point for the big caudofemoralis tail muscle, which would have pulled the leg back for a strong power stroke while running. All dinosaurs had this anatomical feature, but most were not this exaggerated. Camptosaurus must have been quite the speedster!

I’m not sure why the adult is mounted with its legs so straight and its front end bent so low. Maybe it’s supposed to look like it’s paying attention to the little one, which is mounted in a much more natural position.

Here’s Allosaurus sitting as if on a nest, an unusual artistic choice for a non-oviraptorosaur. Overall, the anatomy looks really good. But hold on–what the heck is going on in that art piece behind it? A fluffy baby Allosaurus is being kidnapped by…. what? A monster from the movie 65? An anachronistic, predatory silesaurid? I have no idea what this is supposed to be.

Here’s the back end of Diplodocus, which is really difficult to capture in one photo. You can also see another view of Allosaurus’s head, since in the previous picture there was a lot of glare there, and a top view of the Camptosaurus adult, in the lower left corner. It kind of looks like Allosaurus was just sitting on its nest when all these other dinosaurs started tromping by. Allosaurus looks like it’s saying, “Hey! Watch where you’re walking, ya big oaf!”

See what I mean by “hard to capture in one photo”?

Next to Diplodocus is a mounted skeleton of the much shorter-necked and shorter-tailed Camarasaurus. Look at how sturdy that pelvis is! That’s one thing side-view skeletals don’t tell you.

Here are the heads of Diplodocus and Camarasaurus mounted down low where visitors can see them in detail. They’re shaped very differently from each other, with Diplodocus (left) looking more like a greyhound while Camarasaurus looks like a boxer dog. This is because Diplodocus would have stripped leaves off branches while Camarasaurus just ate the entire branch. I like that the museum did not have to choose between being able to show the skulls in detail and mounting them in life position–it has enough sauropod skulls (which are very rare, by the way) to do both!

This diorama shows a subadult Diplodocus–maybe they decided that an adult wouldn’t fit in the length of the case at this scale–and Ceratosaurus, this time with the upper hand over Stegosaurus. Oh, how the tables turn!

Overall, I’d give the Jurassic section a 9 out of 10. There are some odd quirks, but the sheer density of magnificent skeletons can’t be beat.

Cretaceous Exhibit

Now for the last of the exhibits I’ll look at in detail, the Cretaceous! There was no “Cretaceous Seas” section in the Hall of Fossils, probably because it’s covered across the Rotunda in the Ocean exhibit. But even over there, there are a lot fewer fossils than from the Jurassic and Triassic–just a Tylosaurus (mosasaur) skull and an elasmosaur (long-necked plesiosaur) fin. I wonder why?

The centerpiece of the entire room is those age-old rivals, Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops. While this pose, with one of rexy’s legs on the trike’s ribs and its jaws clamped on the frill, is very dramatic and victorious-looking, I’m not sure it makes sense. The frill has no meat on it–perhaps rexy is trying to rip off the head to access the neck meat, or to reduce the weight it needs to drag back to the nest? If so, I’m not sure how much success it would have, as Triceratops’s neck is super beefy, to support that enormous heavy head. It’s a minor nitpick, though. The rest of the anatomy is great, especially compared to some other mounted rexes I’ve seen.

To the left of this, there are mounted skeletons of a few smaller contemporaries of the big dinosaurs, including the tough little marsupial Didelphodon, the croc Brachychampsa (probably–I didn’t get a picture of the sign), and the turtle Eubaena.

And to the right, there’s a mounted Thescelosaurus, another small bipedal relative of “duck-bills” which was probably not quite as speedy as Camptosaurus given its smaller trochanter, and a thin-snouted croc whose identification info I also failed to get a picture of.

Lastly, there’s a cast of Edmontosaurus, the big “duck-bill”. Not as exciting as the real fossil monty in the Denver museum, but impressive nonetheless. It also has a noteworthy trochanter, which you can see better on the leg on the far side. Edmontosaurus seems quite lightly built compared to Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops–there’s just a lot less bone here.

Here’s a diorama showing Tyrannosaurus lying in wait, ready to ambush a family of little stripey Edmontosaurus and their parent. The scale looks off–rexy looks much too big, or the adult monty too small. But maybe that’s a trick of perspective.

Overall, I’d give the Cretaceous section an 8 out of 10. Beautiful fossils, but only covering the Hell Creek biota. Maybe the amount of detail is inversely correlated with the average size of the specimens, as if each exhibit has a fixed allotment of floor space.

Cenozoic Exhibit

I moved through the Cenozoic area pretty quickly, as the people I’d come with were running out of steam. I won’t comment much because I didn’t get a chance to look at the signage, but here are some pretty photos of fossils.

Uintatherium, an Eocene mammal with weird bosses on its head, which, like the above-mentioned dicynodonts, was an herbivore despite the saber teeth, and a croc I didn’t stop to identify. Showing my anti-croc bias, I guess! Uintatherium was one of the first multi-tonne animals to arise after the extinction that killed the non-avian dinosaurs.

The giant Paleogene bird Gastornis, labeled outdatedly (as of 1997) as Diatryma, a junior synonym. The mounting armature is nearly invisible here. Also, its hands are missing.

This huge mammoth greets you when you enter the Hall of Fossils. It does seem like a good candidate for that–look at all the admirers!

The huge-antlered Irish elk, Megaloceros, in the Ice Age section.

The tank-like armadillo Glyptodon. While glyptodonts are often compared to VW Beetles, this one was more the size of an over-full shopping cart.

Last but not least, here’s an enormous model of Carcharocles megalodon hanging next to the food court. It’s hard to convey just how massive this thing was. It could easily swallow me whole without batting an eye. This model assumes that the meg was proportioned like a great white, which is a reasonable assumption, but is not confirmed since we only have fossil jaws and teeth. What if it were a small shark with a huge mouth?

Conclusion

There’s so much more I didn’t include, such as the entire Ocean Hall, which has a paleontology section with big fossil whales among other things, and the Early Humans area, which has a lot of information about human evolution and current climate change. Plus, it’s free! You can take as long as you want to explore all the levels. The exhibits are well thought out and obviously well funded. It makes me happy that our country cares enough about science education and natural history to fund something like this and make it totally free to the public. Highly recommended!