In the modern world, we currently have some pretty good flightless birds, such as the 150-kilogram ostrich (which only has two toes per foot–don’t let poorly researched cartoons convince you it has three), the fearsome casqued cassowary, the giant cormorant, penguins of various stripes, and the kakapo (a New Zealand flightless parrot), just to name a few. But in the past, there have been many avian groups that have independently evolved both flightlessness and truly massive body sizes. This post will be a fly-by overview–sorry, a run-by side-view–of some of these impressive extinct birds: the phorusracids (“terror birds”), the gastornithiformes (“demon ducks”), the aepyornithids (“elephant birds”), and the dinornithiformes (moa). I’ll also give honorable mention to a few additional large-bodied extinct relatives of living birds at the end.

1. Terror Birds (Phorusracidae)

Family tree: Dinosauria > Theropoda > Avialae > Neognathae > Neoaves > Cariamiformes

Hometown: South America, 62 to 1.8 million years ago (early Paleocene to early Pleistocene)

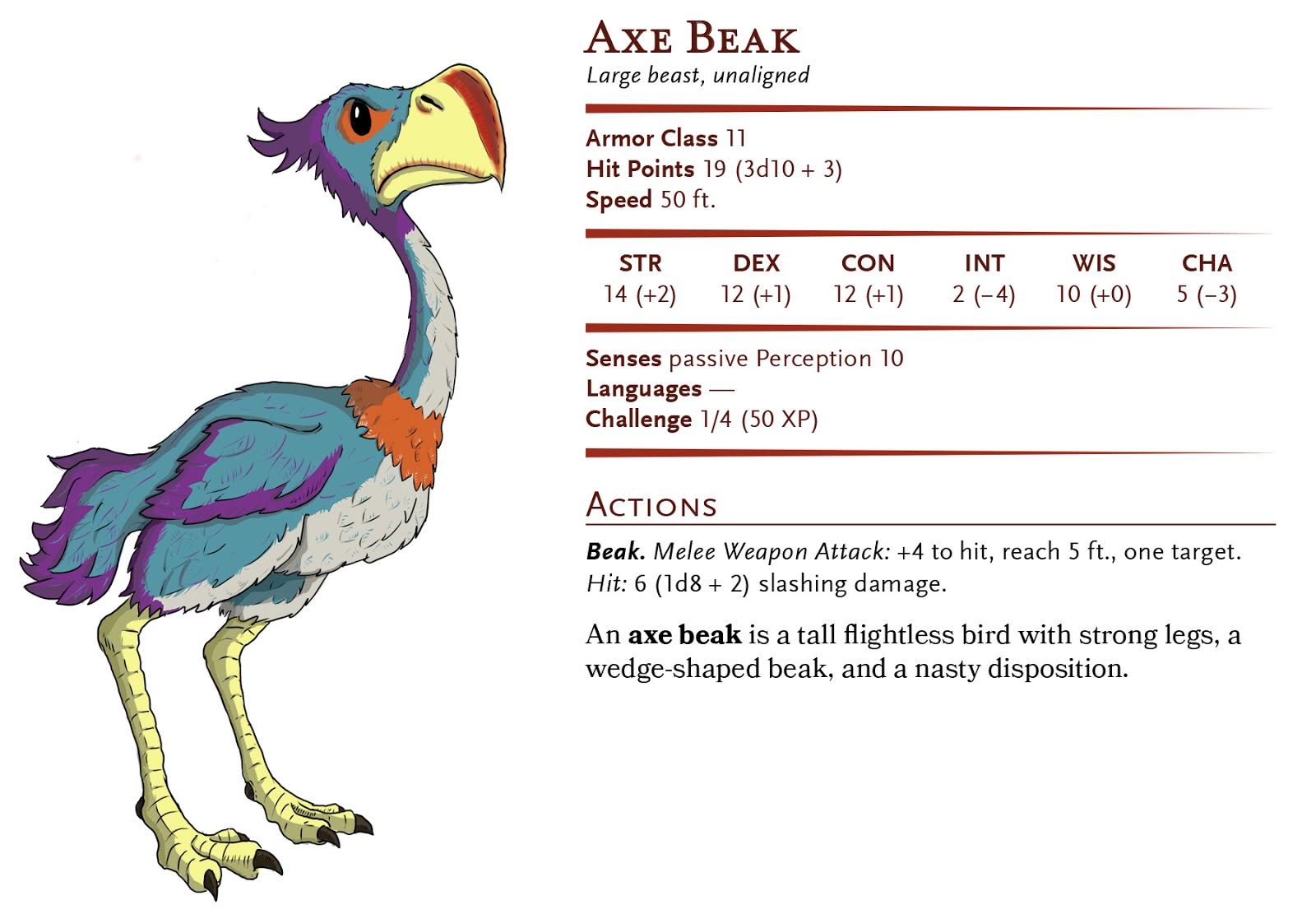

If you’ve played Dungeons and Dragons, you may have heard of the creature known as an “Axe Beak”:

While a majority of the creatures in the game are pure fantasy, this one is based on a real extinct animal: the giant flightless predator from South America, the terror bird, or phorusrhacid (meaning “branch holder” because the original fragmentary remains of Phorusrhacos were thought to belong to a sloth). These relatives of modern seriemas had huge foot claws that they would have used to kick and restrain prey before finishing it off with powerful axe-like pecks. The largest member of this group, Kelenken, from Miocene Argentina, could weigh an estimated 250 kilograms and had the largest skull of any known bird. (They weren’t the largest ever birds by a long shot–keep reading to find out about those–but they had proportionally huge heads.)

Terror birds appeared just four million years after the asteroid impact killed the non-avian dinosaurs, and were essentially the bird family’s attempt at recreating the absent Tyrannosaurus rex. For a majority of their existence, they were confined to the then-island of South America, where they coexisted with a variety of other predators like sparassodonts (marsupial-relative cat-lookalikes–see last week’s post) and sebecosuchians (land crocs). It’s thought that phorusrhacids were scrubland hunters, able to run down prey with their long legs from a starting point within shrubby cover (they were so tall that in completely open habitats prey would’ve been able to see them a mile away).

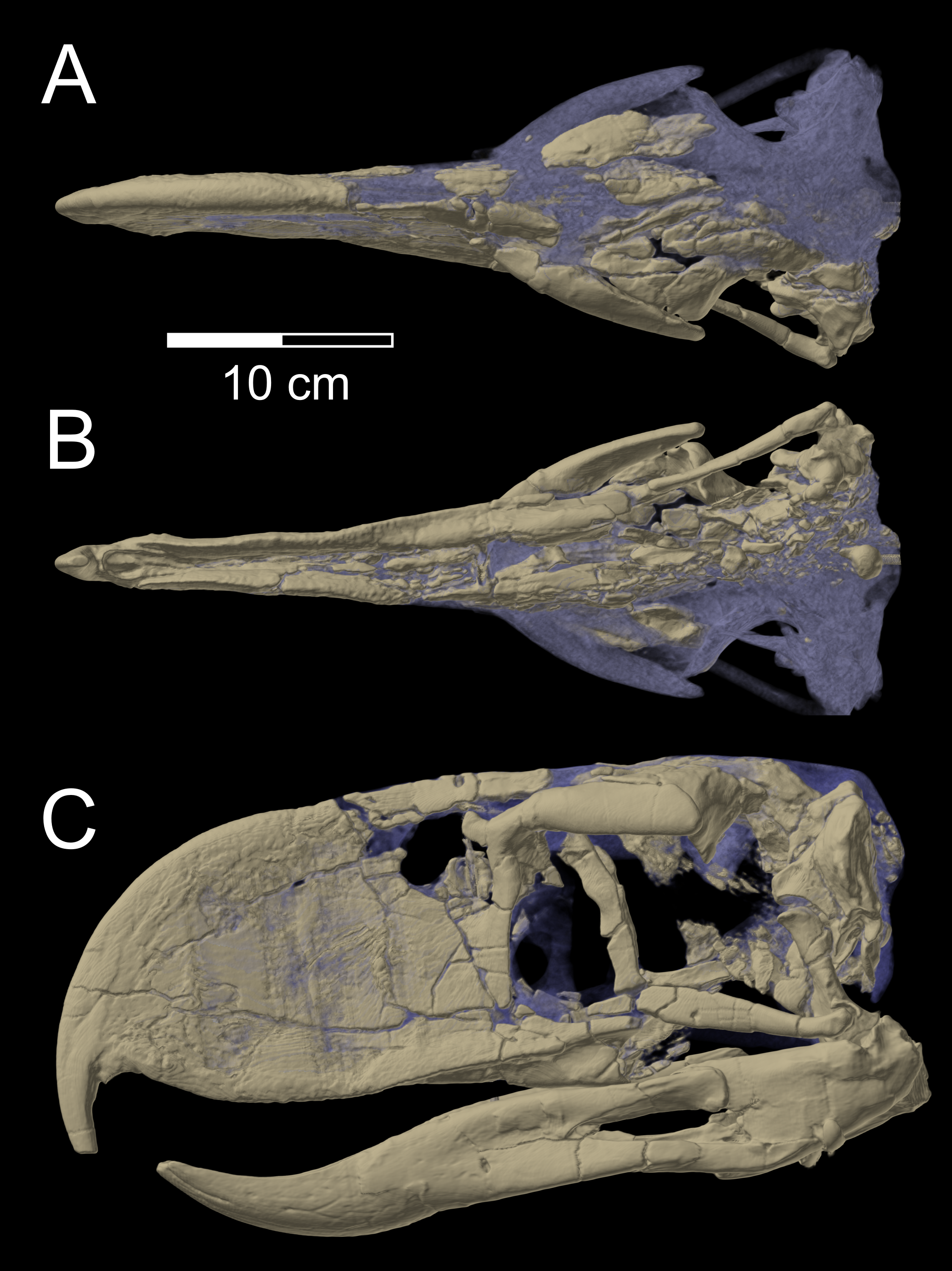

Biomechanical studies on a well-preserved specimen of the smaller, but proportionally bigger-beaked bird Andalgalornis, from late Miocene Argentina (9-6.8 million years ago), showed that the skull was very strong against sagittal loads (up, down, forward, and back) but very weak against medial loads (side to side), and that its neck vertebrae supported musculature that would have enabled strong downward pecks and quick upward recovery to ready another strike. This implies that they would not have attempted to bite live prey like cats or dogs, due to the risk of being injured as the prey struggled, but would have axed it to death, similarly to how Allosaurus and Smilodon (saber-toothed cat) are thought to have hunted, before ripping off swallowable chunks with their hooked beak, similarly to a hawk or eagle. Hopefully the Titanis in the picture above is just transporting an already dead prey animal to a safer feeding spot?

Enough on how they killed stuff–how did terror birds live the rest of their lives? Based on braincase scans, we know they had good eyesight and hearing but a very poor sense of smell, and were decently intelligent (which makes sense given their close relation to other intelligent birds such as parrots and songbirds). There aren’t any fossil eggs or nests known from phorusrhacids, but presumably they would have nested on the ground and laid eggs similar in size to ostriches based on their pelvic anatomy. We’ve found what may be giant fossil pellets full of the bones of little deerlike animals, which, if that’s truly what they are, would mean that phorusrhacids regurgitated the indigestible parts of their prey like owls. However, the pellets’ identity is disputed; the bones may have been conglomerated by other forces, like a rainstorm washing them into a pit, or a scavenger piling things up in a burrow.

Phorusrhacid beaks were hollow, leading some to hypothesize that they used them as a resonating chamber for making social noises. One suggestion is that they clacked their beaks, like the white stork, or Agnaktor. It’s fun to imagine!

When South America began to connect with North America through a series of islands between 9 and 3 million years ago, at least a few terror birds, the ancestors of Titanis, made the trek north, ending up in Texas and Florida, and surviving until 1.8 million years ago. Originally, some of these bones were thought to have been much younger, possibly even hailing from the same time as humans in the same area, due to having been found in the same deposit as many latest-Pleistocene animals. However, the Titanis bones had been moved from their original location by a river, so no humans have ever seen a live terror bird.

Unlike many animals endemic to South America at the time of the interchange, the southern terror birds were able to coexist with newly arrived North American carnivores for some time. However, the raising of the Andes mountains caused the climate to become much drier across much of their habitat, replacing scrubby forests with open grassland and desert where the terror birds’ tall stature was a detriment. What a shame–they existed for a total of sixty million years, and we just missed them by a measly one million!

Interestingly but maybe not surprisingly, North America had its own convergently evolved terror bird for a time: the bathornithids, which are known from the late Eocene to early Miocene (37-20 million years ago) of the western United States, and are also in the seriema family, but developed flightlessness and large body size independently, descending from a small, flighted ancestor. They could reach heights of up to 2 meters, but were a bit less specialized than their South American cousins, with skinnier beaks, larger wings, and larger halluces (the backward-facing toe).

Similarly to phorusrhacids, bathornithid remains are found in swampy and sparsely forested ecosystems rather than open grasslands. They coexisted alongside large mammalian predators such as nimravids (cat relatives), entelodonts (hell pigs), and hyaenodonts (large basal carnivorans). However, by the time Titanis reached North America, the bathornithids had long been extinct, so there never was a grudge match to determine which bird was best. Too bad!

2. Demon Ducks (Gastornithiformes)

Family tree: Dinosauria > Theropoda > Avialae > Neognathae > Galloanserae > Anseriformes

Hometown: North America, Europe, China, South America, and Australia, 56 to 0.03 million years ago (Paleocene to late Pleistocene)

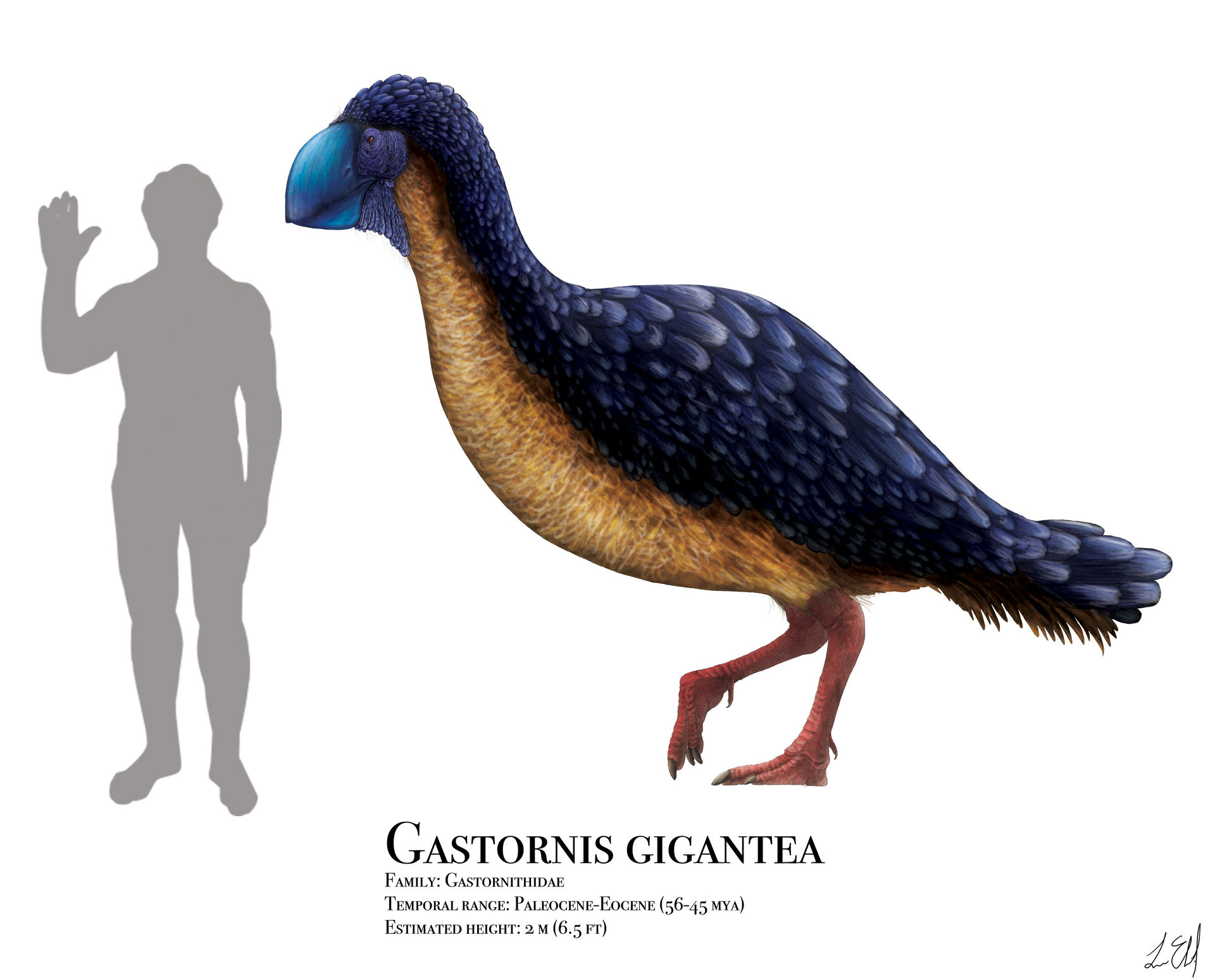

I talked a little about Gastornis in particular in my post on the Messel Pit, so hopefully you’re already a little bit familiar with this family of giant duck relatives. These were long considered a subset of the terror birds, since they outwardly looked very similar and unlike any other known group, but now it’s thought that they were anseriformes (waterfowl), a more basal bird group. Because of this, older paleoart often depicts them as being hypercarnivorous, but many lines of evidence point to an herbivorous or omnivorous lifestyle, including beak shape (sharp, but not hooked), limb anatomy (heavy legs good for walking but not running too fast), feet that lacked sharp claws, and bone chemistry (plants have different isotope proportions than animals, and you are what you eat).

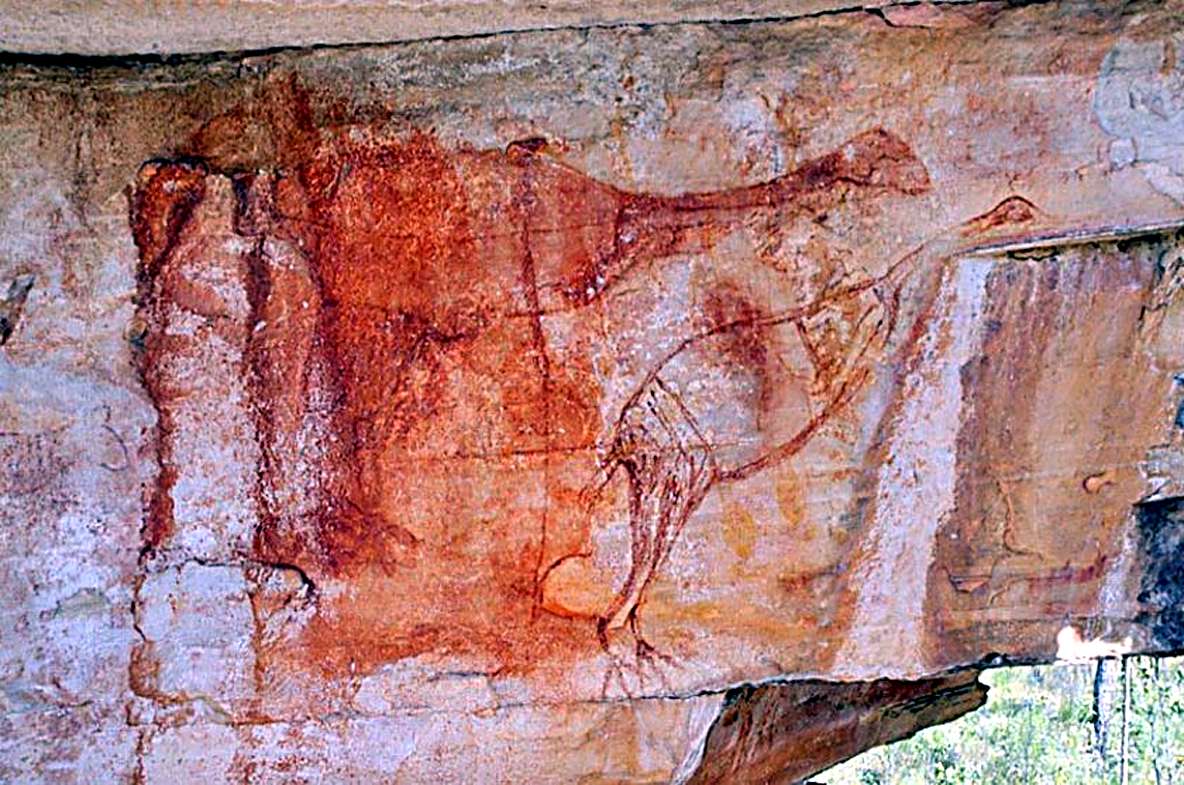

There are three distinct groups within Gastornithiformes that convergently developed large body sizes: the above-mentioned Gastornis, from the Northern Hemisphere, the enormous and enigmatic Brontornis from Miocene Argentina, and the dromornithids, also known as mihirungs (from the Tjapwuring (aboriginal Australian) for “giant bird”), known from Oligocene through Pleistocene Australia. Why do the mihirungs get a common name? Because they lived alongside humans just 40,000 years ago, who made paintings of them!

The largest mihirung, Dromornis stirtoni (there are other species of Dromornis that are much smaller), exhibited pronounced sexual dimorphism, with males weighing up to 580 kilograms, while females only reached 450. They also had teeny-tiny brains similar in structure to that of a chicken. The lead author of the study examining Dromornis’s braincase, Trevor Worthy, said, “I mean, if a chicken is silly, these things were very much more silly.” Who am I to question such sage judgment?

Mihirungs’ bulbous beaks and sideways-facing eyes would have given them an impressively large frontal blind spot of 40 degrees. It’s unknown what this giant beak, and the musculature required to operate it, was for, since there’s no super-tough food known from the environment at the time. Maybe it’s just a display structure, or maybe there was intrasexual competition involving the beaks, like rams butting heads. But with beaks.

Mihirungs lived in semi-arid open woodland where water was scarce, so a wealth of fossils are known from ancient watering holes that dried up, where giant dehydrated birds came to die. Depressing as that picture is, it gives us an indication of their population demographics–they seem to have been relatively common in their environments, and may have formed flocks of around four individuals.

Last but not least of the gastornithiformes is the problematic Brontornis, whose taxonomic placement is still under debate. Its beak is more raptorial than the rest of the demon ducks’, but not as strongly hooked as those of terror birds. It also shares some features of the vertebrae with phorusrhacids, but the main point in favor of its placement among the terror birds is Brontornis’s location: no other gastornithids are known from South America, while terror birds were super common there. Recent studies have supported the placement of Brontornis with the gastornithiformes, but don’t put forward any hypotheses about how its ancestors reached South America or what they might have looked like.

3. Elephant Birds (Aepyornithidae)

Family tree: Dinosauria > Theropoda > Avialae > Palaeognathae > Novaeratitae

Hometown: Madagascar, 34? million years ago to ~1200 AD (Oligocene to Holocene)

I’m sure you’ve heard or read by now that a majority–maybe as high as 99.9 percent–of species don’t fossilize, but if you’re like me, you haven’t really internalized it. Like, maybe most species don’t fossilize, but most families have at least one fossil member so we can at least guess at the presence of its relatives?

Not necessarily–some places, like rainforests and mountains, just don’t produce fossils, so if an animal group is endemic to an unfossiliferous habitat, we will never know it existed. The elephant birds of Madagascar are one such group, which we’re lucky enough to know about because we were there to witness them. If a 730-kilogram bird could be lost to knowledge, imagine what else is probably hiding in the deep past! Makes it hard to be skeptical about extraordinary claims.

Elephant birds were ratites, or members of the group containing emus, kiwis, ostriches, rheas, cassowaries, and tinamous. From genomic evidence, we know that their closest relative is the kiwi, but even they diverged around 54 million years ago, independently evolving flightlessness from a flighted, world-colonizing ancestor. Like kiwis, elephant birds had poor vision and a good sense of smell (the opposite configuration of the terror birds), and probably foraged for fruit by scent in the dark. Many of Madagascar’s large fruit-bearing plants seem to be suffering from Megafaunal Dispersal Syndrome (though of course there are probably lots of slightly more ancient megafauna from Madagascar that just didn’t fossilize, and are also candidates for coevolutionary partners of those fruits).

People often think of animals as superior at navigating nature, able to move ninja-silent through the forest in a way only rivalled by Native Americans. This is not the case. While animals are often able to be remarkably patient and stay still for long stretches without making noise, when they move they’re as prone to breaking sticks and crackling leaves as the rest of us. Imagine what a racket half-blind three-quarter-tonne birds would have made crashing about in complete darkness!

There are only three known genera of elephant bird: the above-pictured Aepyornis; the smaller, slightly less nocturnal Mullerornis; and a genus recently distinguished from Aepyornis, the largest bird ever to live, Vorombe. In addition to being the largest birds, elephant birds laid the largest eggs of any bird, and possibly the third-largest of any animal, at 34 centimeters long and weighing up to 10 kilograms. Humans used the shells as soup bowls, and a single egg would feed a large family. That’s especially impressive given that Vorombe is not the largest animal by a large margin–multi-tonne sauropod (long-necked) and hadrosaurid (duck-billed) dinosaurs laid small eggs for their body sizes. The only other animal groups whose egg size surpassed that of elephant birds are theropod dinosaurs closely related to birds, such as Tyrannosaurus, with eggs estimated at 43 centimeters long (no actual eggs are known, but fossilized embryos have been found), and giant oviraptorosaurs like Gigantoraptor, with eggs up to 60 centimeters long (that’s like a five-gallon fishtank!).

Unfortunately, if you Google “largest egg ever,” the OneBox at the top suggests “elephant bird”, which is incorrect, no offense to elephant birds. Read more about record-breaking eggs here, here, and here.

4. Moa (Dinornithiformes)

Family tree: Dinosauria > Theropoda > Avialae > Palaeognathae > Notopalaeognathae

Hometown: New Zealand, 17 million years ago to ~1400 AD (Miocene to Holocene)

Why is it that the Southern Hemisphere got all the kickass birds? With singleton exceptions here and there like Gastornis and Titanis, all of the birds in this post are endemic to islands south of the equator. Island gigantism, I get it, but there are islands in the north as well! Was there something keeping birds from getting huge on islands up here? All those island dwarf elephants looking pretty sus right about now…

Even among giant-bird-evolving islands, New Zealand takes islanding to another level. It has no native mammals other than bats and aquatic mammals, so birds filled many of the roles mammals usually occupy. This resulted in the very ratlike kiwi, the very opossum-like kakapo (flightless parrot), and the llama-like moa. Another ratite lineage, moa were herbivores varying in size from the turkey-sized little bush moa to the 230-kilogram giant moa, and covering everything in between. Before the arrival of humans, their only natural predator was the huge Haast’s eagle. At fifteen kilgrams, Haast’s eagle was huge for a bird of prey, but probably unable to tackle a full-grown giant moa. Modern six-kilogram eagles can kill eighteen-kilogram goats; even generously scaling that up exponentially would only give a maximum prey size of 135 kilograms for Haast’s eagle. Still plenty of margin to prey on humans though!

Giant moa had some of the most extreme sexual dimorphism of any birds, with the females standing twice as tall and weighing three times as much as the males, which were around the size of a medium-small ostrich. We don’t really know why this was the case–it’s suggested that the larger a bird is, the more pronounced ancestral dimorphism becomes, but how did the ancestral dimorphism begin in the first place? The females of birds of prey and certain shorebirds are also larger, but the reason for that is unknown as well. In most birds (and most animals), the male is larger due to intraspecific competition for access to females.

Moa were most closely related to modern tinamous, which live in Mesoamerica and are the only flighted surviving ratites. Similarly to all the other big flightless birds in this post, moa evolved from ancestors that dispersed across the globe by flying, and became flightless independently.

The moa’s downturned beak worked similarly to pruning shears, allowing it to effectively clip tough plants and twigs. It further processed these using fancy gizzard stones, preferring quartz pebbles over others, probably on the basis of prettiness, but with the effect of choosing harder stones that would do a better job mashing plant matter. They grew slowly, with both large and small genera taking around a decade to reach adult size, and laid super thin-shelled eggs which would have been incubated by the male (we know this from DNA recovered from the outside of eggshells! We are living in the future!). They also had no arms at all, the only known bird with this condition. Hesperornis, a toothed waterbird from the Cretaceous period, is nearly there, with arms reduced to a single, toothpick-like bone, but the moa gets big points for 100% completion.

Moa suffered the fate of many endemic fauna when exposed to humans: they were quickly overhunted to extinction during the century following human arrival. Since this happened so recently though, and moa remains are so plentiful, scientists have been able to sequence their genome, and thus put them in the queue for resurrection via cloning once we’re reliably able to do that.

Other notable mentions

I thought about including a section on Palaeeudyptinae, or giant ancient penguins, but I was running out of steam, and anyway giant penguins were not that big compared to the other birds on this list (the largest, Palaeeudyptes klekowskii, weighed up to 115 kilograms). If you want to learn more about them though, PBS Eons has a nice episode on the topic.

I also must mention Pachystruthio, the fourth-heaviest bird, and close relative of the modern ostrich, which lived in Europe and China during the Pliocene and Pleistocene and could reach an estimated weight of up to 450 kilograms. However, it’s only known from two thighbones belonging to two different individuals, so we know almost nothing about its lifestyle. The thighbones are slender for how big they are, indicating that perhaps Pachystruthio was a faster runner than other giant birds.

Other large relatives of familiar modern birds include the 22-kilogram goose from Miocene Italy, Garganornis; the 14-kilogram owl from Pleistocene Cuba, Ornimegalonyx, which was flight-capable but had long legs for running; and the 5-kilogram flightless cormorant from the Galapagos, which is actually still extant.

The page image depicts Dromornis, the demon duck, embracing its waterfowl roots. It was by no means adapted for an aquatic lifestyle, but even ostriches go swimming sometimes. Perhaps it was a particularly hot day, and these two buddies–brothers?–were in the mood for a dip. I did this in a style somewhat inspired by Joschua Knüppe’s Paleostream, in which he creates digital paleoart from crowd suggestions as fast as possible. I was doing this picture as fast as possible as well, and I think it’s definitely a good low-effort-high-reward style. I’ll probably do more like this in the future. Quack, am duck, pls throw bread.

Image Credits:

Axe Beak Titanis Andalgalornis Bathornis Gastornis Genyornis Dromornis Brontornis Aepyornis Dinornis Pachystruthio