Every so often, a scientific paper comes out that rocks the paleontology community and gets paleoartists flocking to make updated depictions reflecting the new information. In the past I’ve done a couple of Obscure Dinosaur Profiles prompted by such developments, like the one on the nocturnal bug-eating dinosaur Shuvuuia and the two strange little ankylosaurs Spicomellus and Stegouros.Just recently, there were two such papers: one on the swimming habits (or lack thereof) of various spinosaurs, and one on the life appearance of the sauropods with the ostentatiously high-spined necks, known as dicraeosaurids. Here, I will give you a rundown on each, and why everyone is so excited about it!

Sauropod Sails

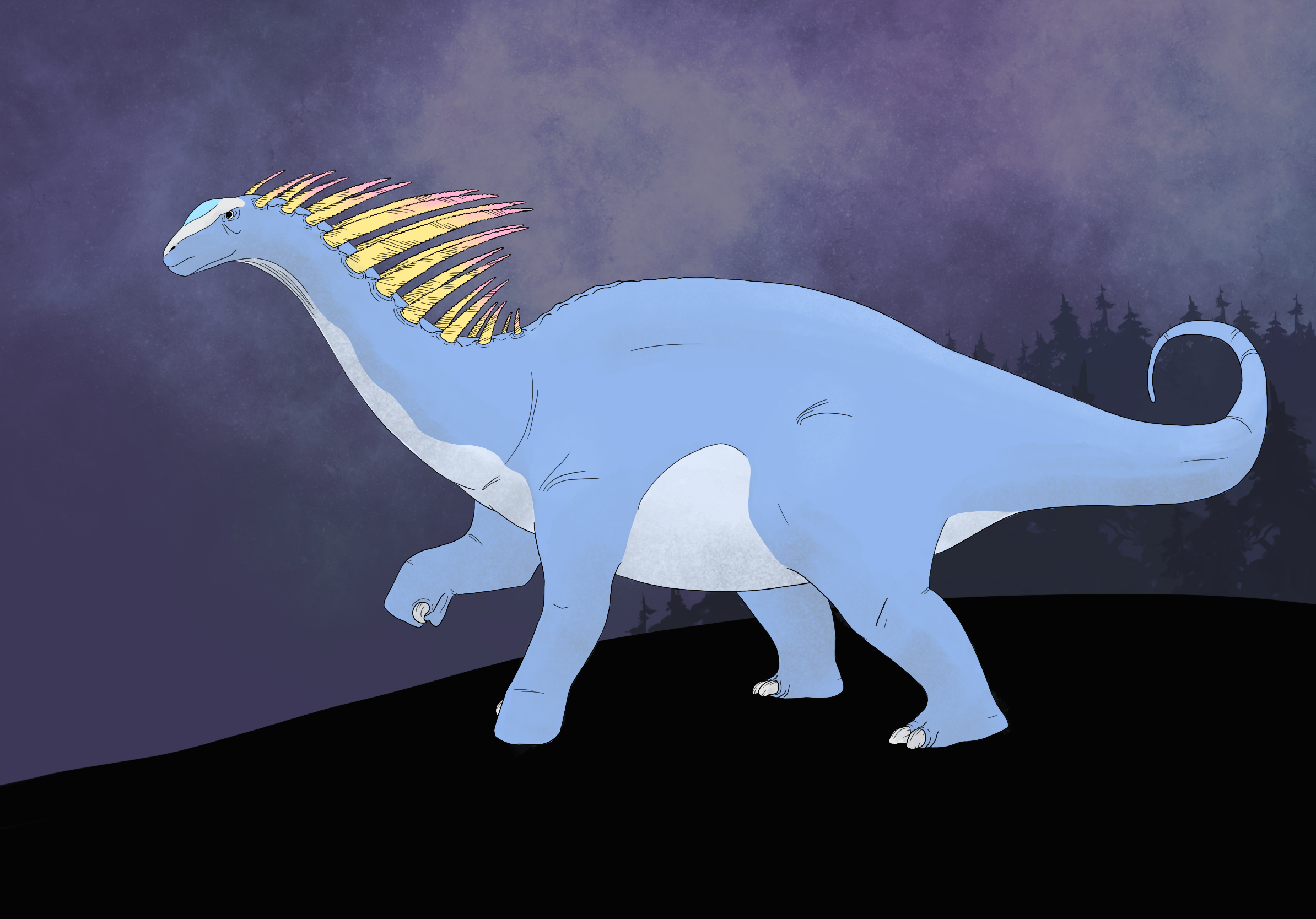

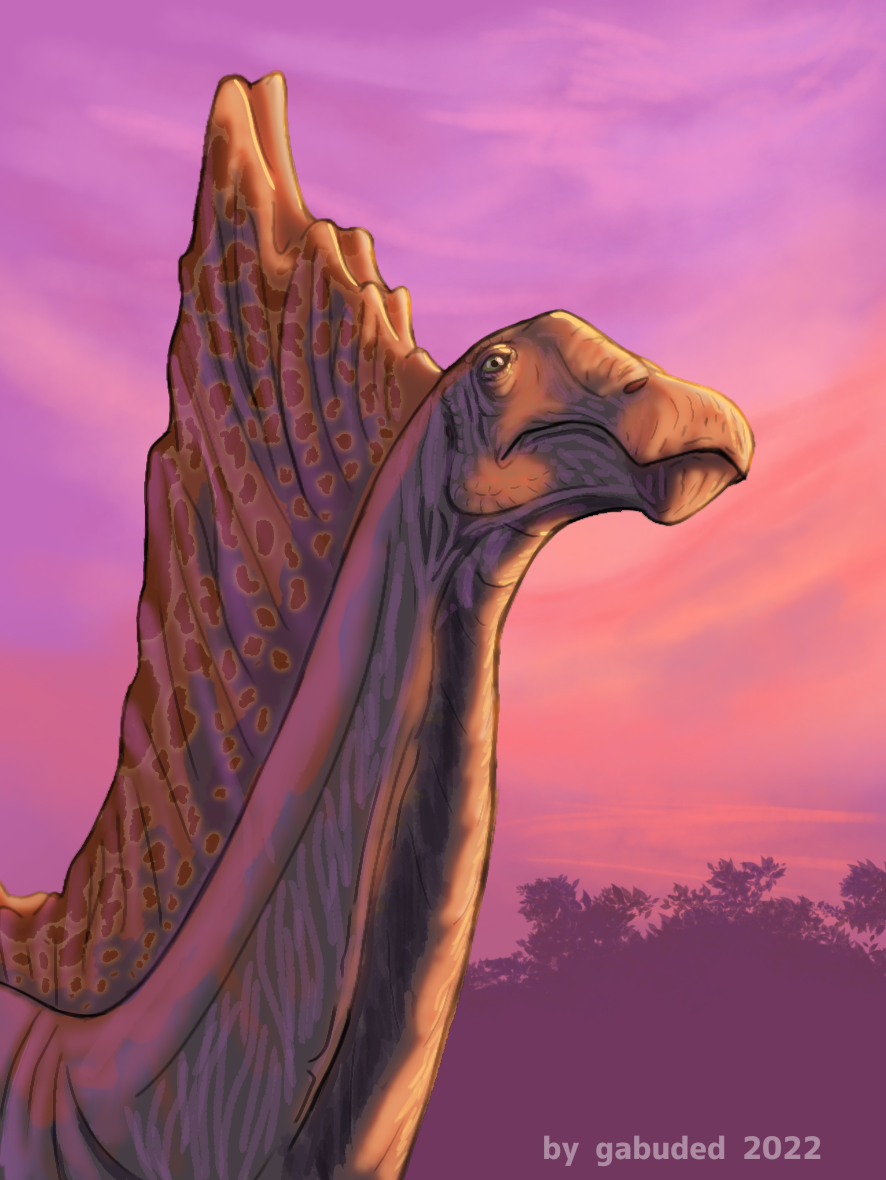

Sauropods (long-necked dinosaurs) came in a variety of shapes and sizes, but dicraeosaurids (meaning “bifurcated reptiles”), from Early Cretaceous South America, are some of the most puzzling. They had rather short necks for sauropods, and are thought to have held them in a more horizontal or downward-facing posture than other sauropods, hypothesized to be efficient grazers rather than high-browsers. And some of them–Dicraeosaurus, Amargasaurus, and Bajadasaurus–had hyper-elongated neural spines (the sticking-out part of the vertebrae). Dicraeosaurus’s spines were mostly straight, rather modest, and blunt-ended, but Amargasaurus had long, pointy, backward-swept spines while Bajadasaurus’s were even longer and forward-raked. What were these extreme structures for?

A number of hypotheses have been suggested over the years–that they were connected by a flap of skin, kind of like a Draco lizard’s “wings”; that they supported a fatty hump like a bison, or huge muscles for lifting the neck; or that they were horn cores covered in keratin, like a longhorn cow. That last interpretation has been the frontrunner for the past few years, the idea being that the horns would have deterred predators from attacking while the animal had its head down, grazing.

However, the new paper, catchily titled “Osteohistology of the hyperelongate hemispinous processes of Amargasaurus cazaui (Dinosauria: Sauropoda): Implications for soft tissue reconstruction and functional significance”, comes to a different conclusion. In the first histological look at dicraeosaurid remains (taking thin slices of the bone and looking at the structure under a microscope), the authors concluded that the bone microstructure indicates that the spines would not have supported a keratin sheath, but rather a system of ligaments, covered in skin, that would have formed a chunky sail. This structure almost certainly would have been used in sexual display, but we don’t have enough fossils yet to know if there was sexual dimorphism, or differences between males and females. The chunky sail would probably also have protected the neck from biting attacks by keeping predators further away.

While the new study only looked at Amargasaurus remains, the results probably also apply to its close relatives, including the cooler-spined Bajadasaurus, prompting a storm of paleoart featuring that dinosaur as well.

To me, these chunky sails look super inflexible, like they ought to severely limit neck mobility. Perhaps there was a break in the sail between neck and back to allow for the head to be fully raised and lowered? Or perhaps these dinosaurs just didn’t move their heads all that much?

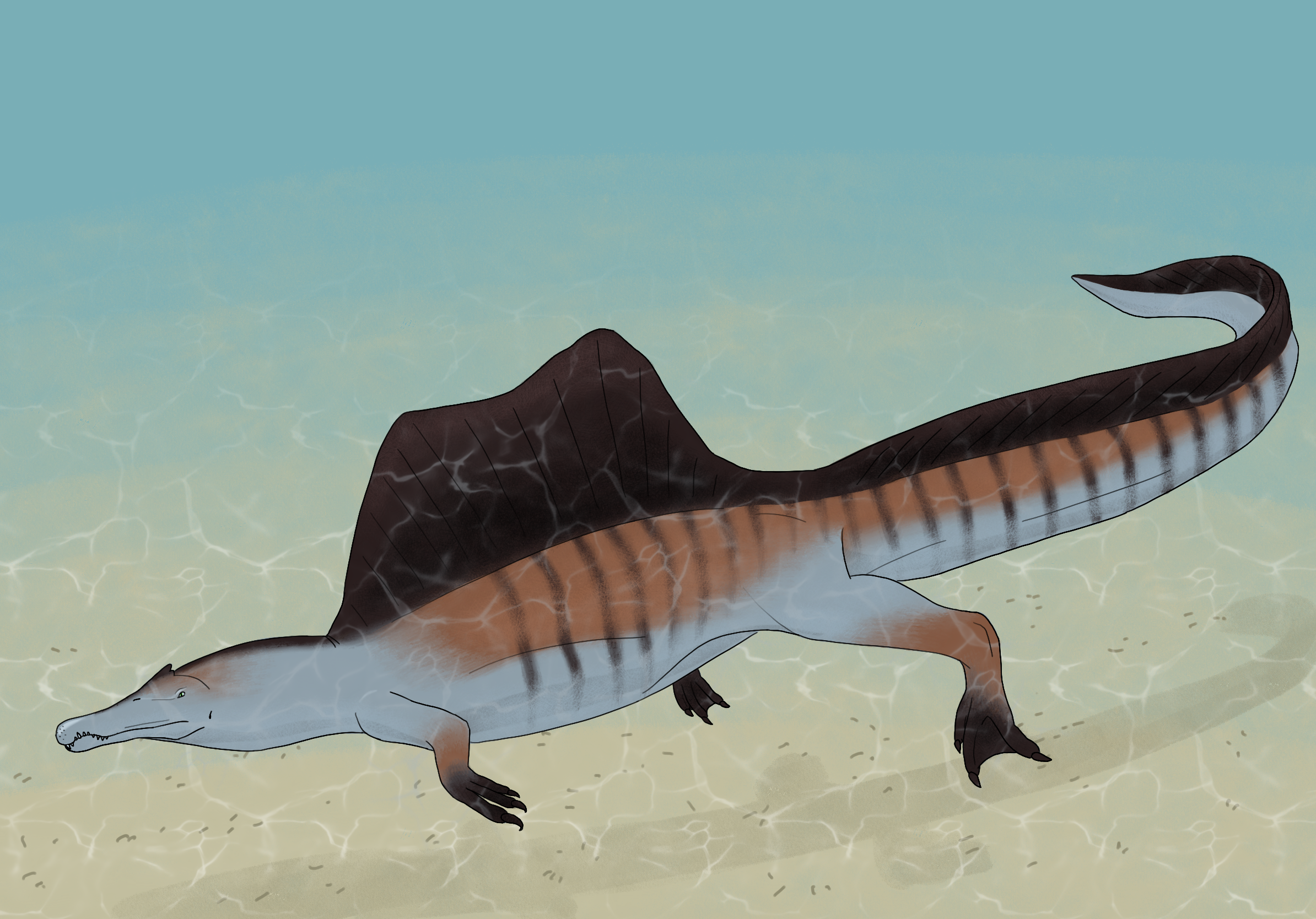

Spinosaur Swimming

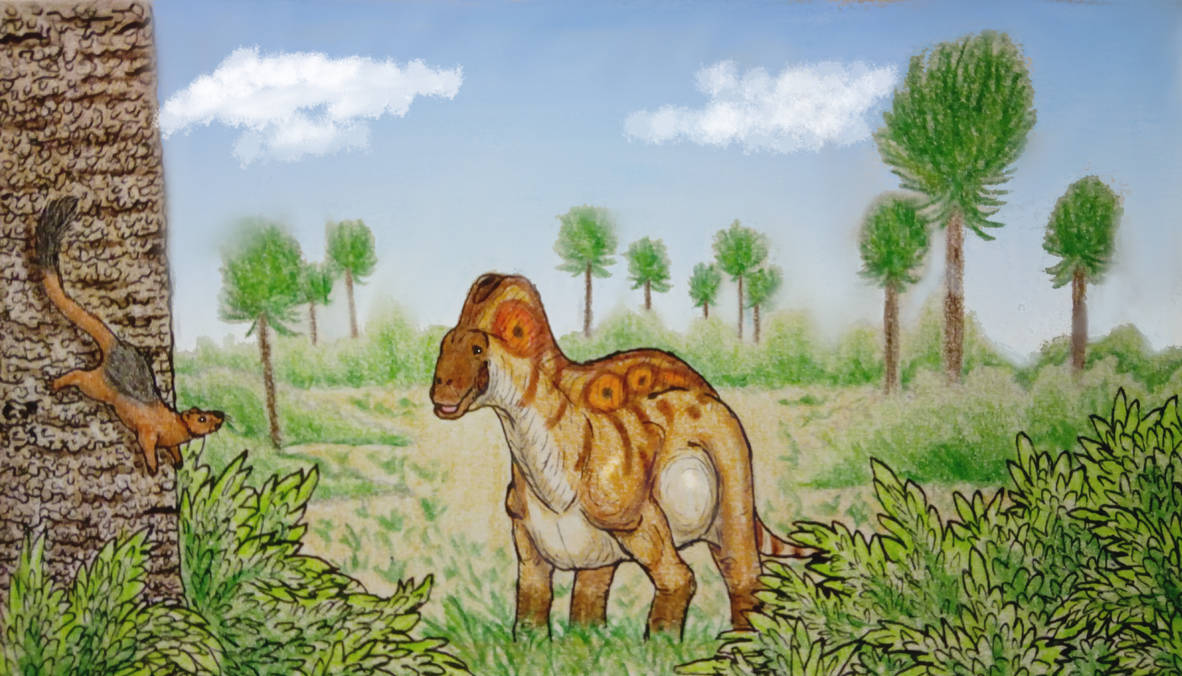

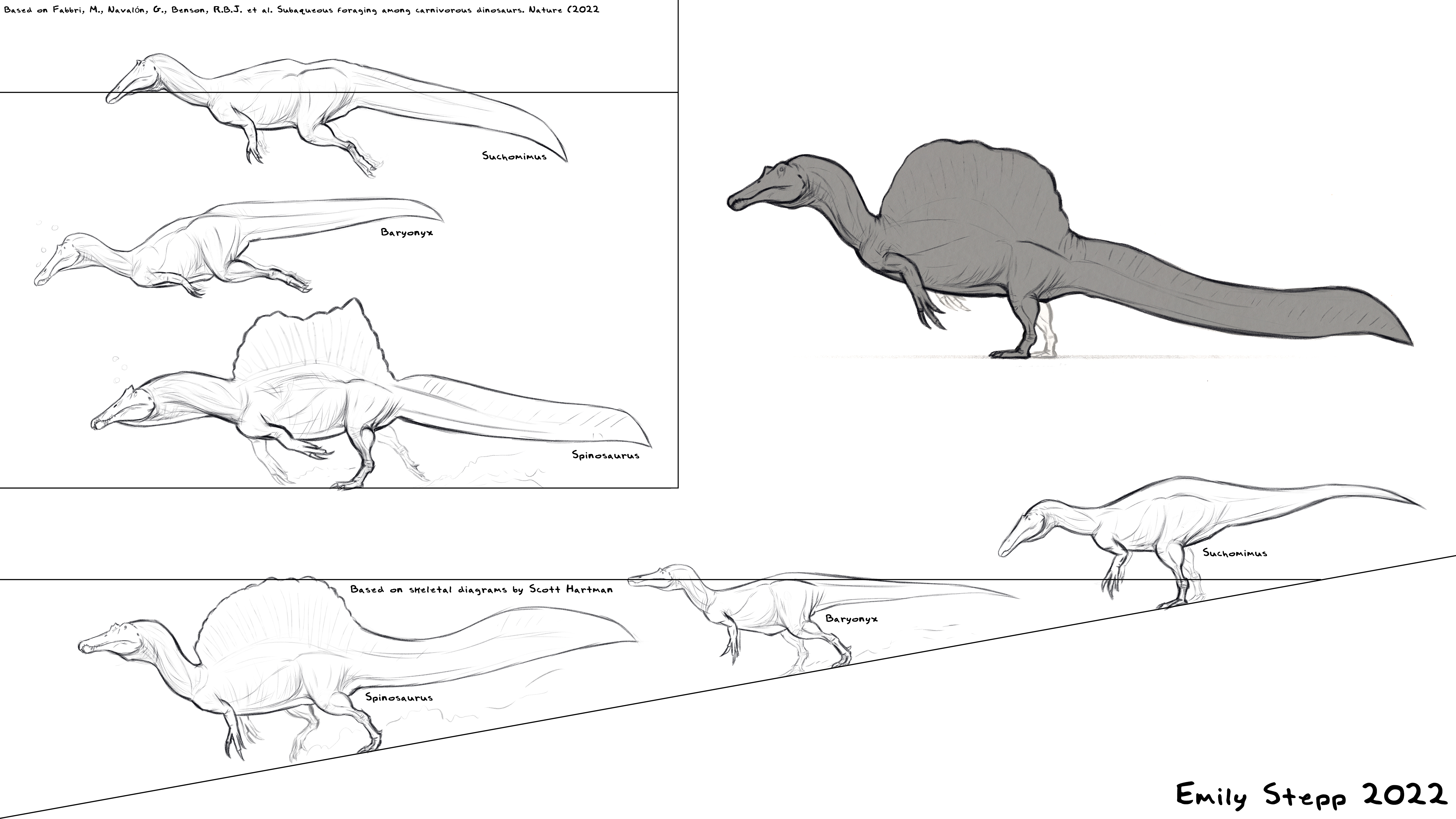

Spinosaurs were large theropods (bipedal, meat-eating dinosaurs) most diverse in early Late Cretaceous Africa and South America, which were unusual among theropods for their long, croc-like faces and conical, fish-catching teeth. Famous members include Spinosaurus (often touted as the largest carnivorous dinosaur; it was in the same weight class as Tyrannosaurus but was a bit longer and thinner), which had an impressive, possibly M-shaped sail on its back as well as a tall, newt-like tail and webbed feet; Irritator, a much smaller animal, so named because the authors were irritated that the remains had been tampered with; Baryonyx of Jurassic World fame; Ichthyovenator, meaning “fish hunter”, which had a very strangely-shaped kinked sail; and Suchomimus, which means “croc mimic”. All of them shared the long, slender face with a croc-like rosette at the front, and Baryonyx remains have even been found with fish inside, indicating that this group was at least somewhat tied to the water. But there are a lot of degrees of aquaticism, ranging from the mostly-terrestrial grizzly bear, which eats a lot of fish but doesn’t really swim, to waterbirds like herons, which stand in water and live by water but don’t really swim, to crocs, which are mostly-aquatic but often hunt terrestrial prey at the water’s edge, to fully-aquatic pursuit hunters like seals and penguins. Where did spinosaurids fall on this spectrum?

The debate has been ongoing for years, and has generally been trending more and more aquatic as we learn more about these animals. The last big development before this most recent paper was the announcement of Spinosaurus’s fin-shaped tail, in 2020:

But Spinosaurus isn’t exactly a typical spinosaurid, so it was still unknown how aquatic the other members of the family were. This paper tried to answer that by investigating the bone density and structure of not only three genera of spinosaurid, but lots of terrestrial, semi-aquatic, and aquatic living animals as well. Dense bones have long been thought to be an adaptation for a more aquatic lifestyle to aid in overcoming air-breathing animals’ natural buoyancy; hippos and penguins are notable for having much denser bones than their terrestrial close relatives. But these authors wanted a more rigorous correlation, so they built a large dataset of whether bone density predicts how aquatic an animal’s lifestyle is using living animals whose lifestyles are known, and then measured spinosaurid bone density to predict their lifestyle in the sme way.

What they found was rather interesting: Spinosaurus, predictably, was highly aquatic, with very dense bones, but Baryonyx showed a strong affinity for water as well, with bones not as dense as Spinosaurus’s but much denser than water-adjacent animals’. And Suchomimus, which is very similar to Baryonyx in appearance, had bones that appeared almost completely terrestrial.

Dr. Nizar Ibrahim, the lead author on the Spinosaurus tail description paper in 2020 and the senior author on this latest paper, goes one further to claim that Spinosaurus would have actively pursued prey in the water like a seal or penguin, but many paleontologists (including me) believe it more likely that it would have been a croc-like ambush predator that swam at a moderate pace just to get from place to place.

My page image up top depicts Suchomimus, the least-aquatic of the three genera investigated in the study. It’s standing on one foot, a behavior common among waterbirds that’s thought to be advantageous for a few reasons: to reduce heat loss to the water, to rest (akin to crossing one’s legs or slouching), and to give half the brain a break. I’m not sure a creature this large would find it as nice as a goose does–Suchomimus weighed up to five tonnes–but it would at least have been capable of it, being a biped.

Image Credits

Bajadasaurus skeleton Bajadasaurus Amargasaurus Spinos Spinosaurus Amargasaurus paper Amargasaurus article Spinosaurus paper Spinosaurus article