As I’ve discussed previously, sauropods (long-necked dinosaurs) had a suite of adaptations that allowed them to reach tremendous sizes, never seen before or since in a land animal. Several groups of sauropods, all within the clade Gravisauria (meaning “heavy reptiles”) independently evolved body sizes of 50, 75, or possibly even up to 100 tonnes. Some of those adaptations, such as egg laying and a system of air sacs and flow-through lungs that improved respiratory efficiency, are shared with all dinosaurs, but sauropods’ skeletal adaptations for weight bearing are unique to that clade. They had zero fingers on the front feet, instead having a horseshoe-shaped column of bones–some retained one claw on the thumb, but no other fingers would have been visible–and their back feet had a large fleshy pad like that of an elephant to help spread the weight. All of their limbs were very column-like, with the joints held in a vertical stack, to better transmit weight without introducing levers that would require muscles to resist. While these adaptations were necessary for reaching truly huge body sizes, some other dinosaurs lacking them reached impressive sizes as well–while not on quite the same scale, they were still larger than any land animal alive today. This isn’t the case for most dinosaur groups–it seems that African bush elephant size, up to 10 tonnes (22,000 pounds), represents a kind of natural optimum for large land animals, and many dinosaur groups had one or more representatives at that limit, including tyrannosaurs, carcharodontosaurs, spinosaurs, ceratopsians, stegosaurs, and ankylosaurs. However, some non-gravisaurian dinosaurs did exceed this limit, reaching estimated weights of 12 to 16 tonnes. In this post, we’ll take a look at the biggest of the less-big.

About graviportal adaptations

First of all, I’d like to cover a couple of baseline concepts that will be helpful later on in this rather technical post. What does “graviportal” mean in terms of specific traits? And if graviportal adaptations are so great, why doesn’t every animal have them?

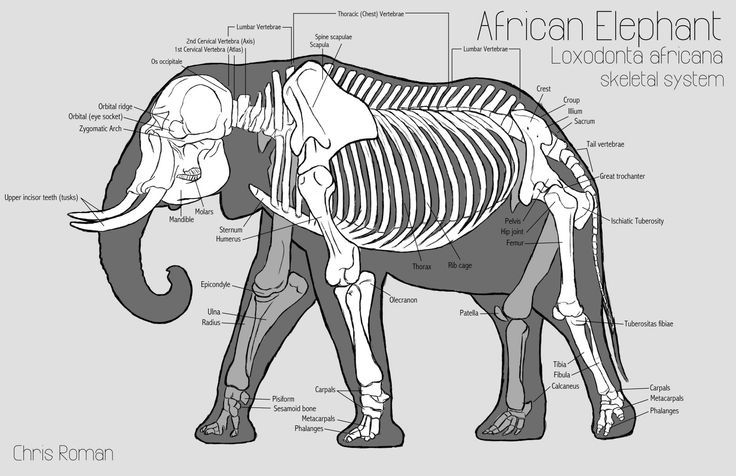

To understand graviportality better, let’s first look at the opposite: cursoriality, or adaptations for running fast and/or far. Cursorial animals tend to share a suite of morphological modifications, such as long limbs for increased stride length; blunt, hoof-like nails used for increased traction; and proportionally short upper limbs compared to elongated lower limbs (numerically classified as a high cursorial limb proportion score). Contrast the skeleton of an African elephant with that of a Chinese water deer–a highly cursorial, small animal–below:

The humerus and femur of the water deer are proportionally short compared to the rest of the leg, and held at a nearly 90-degree angle. The humerus and femur of the elephant are almost the same length as the whole rest of the leg, and the whole leg is held in a near-vertical stack. The shortening of the humerus and femur in the water deer allows for more of the animal’s muscle mass to be concentrated in the torso rather than out toward the ends of the limbs, making the limb effectively lighter and easier to swing fast through its stroke. And the strong angle of the water deer’s limbs allows it to use leverage to push itself forward and upward powerfully. However, that same leverage and concentration of weight up high become a hindrance at too large of sizes: the animal’s body weight pushes down on the horizontal upper arms and legs, requiring lots of muscular effort to not just collapse; and a high center of mass makes a large animal more prone to tipping over. Also, an overly skinny leg on a large animal becomes more prone to breaking, and adding some muscle and sinew distally helps to reinforce the limb.

Elephants and sauropods have very similar graviportal body plans, while the animals I’m going to focus on in this post did not.

Lessemsaurids

Lessemsaurids, named after author, paleontologist, and animatronics builder Don Lessem, were a primitive group of non-gravisaurian sauropods from the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic of South America and southern Africa. They were the first group of animals to reach truly enormous sizes, and they did it independently, unrelated to the families of gravisaurian sauropods that would later thunder across the Mesozoic landscape. The last common ancestor shared by gravisaurians and lessemsaurids probably looked like the Late Triassic “prosauropod” Melanorosaurus–

–which was certainly a big animal at around 1.3 tonnes (between cow and hippo-sized), but nowhere near the prodigious masses achieved by both branches of its descendants.

Note: When I say “probably looked like,” I mean that while Melanorosaurus is almost certainly not the direct ancestor of all sauropods, it is very closely related to that ancestor and is therefore likely similar to it. The ancestor of sauropods probably shared traits with Melanorosaurus like teeth suited for omnivory, medium body size (for a dinosaur), a medium-long neck, and a quadrupedal gait. That means that any adaptations shared by its descendants that Melanorosaurus did not share must have been evolved independently.

Lessemsauridae includes the huge quadrupeds Lessemsaurus (estimated at seven tonnes), Antetonitrus (a modest two tonnes), Ingentia (possibly up to nine tonnes), and the newest addition, the 2018-described giant Ledumahadi (twelve tonnes). It may also include the lighter-built, bipedal Kholumolumo and Meroktenos, which, if it ends up being true, provide examples of some members of this group retaining ancestral characteristics.

Above: Kholumolumo, a genus of possibly lessemsaurid dinosaur described just recently in 2020, but based on material that had been unearthed over the decades between 1930 and 1970 and had just been sitting in collections, unstudied.

While gravisaurian sauropods like Barapasaurus had reached large sizes as well by the Early Jurassic (estimated at seven tonnes), and their descendants would go on to rule the earth for the rest of the Mesozoic while the lessemsaurids died out before the Middle Jurassic, Ledumahadi was the largest known land animal to have lived up to that time. (Ichthyosaurs, whale-like marine reptiles, reached truly huge sizes long before that, as early as the Middle Triassic, with the recently-described giant Cymbospondylus youngorum.) So for a short time, in the battle between lessemsaurids and gravisaurians for the enormous-herbivore niche, lessemsaurids were winning.

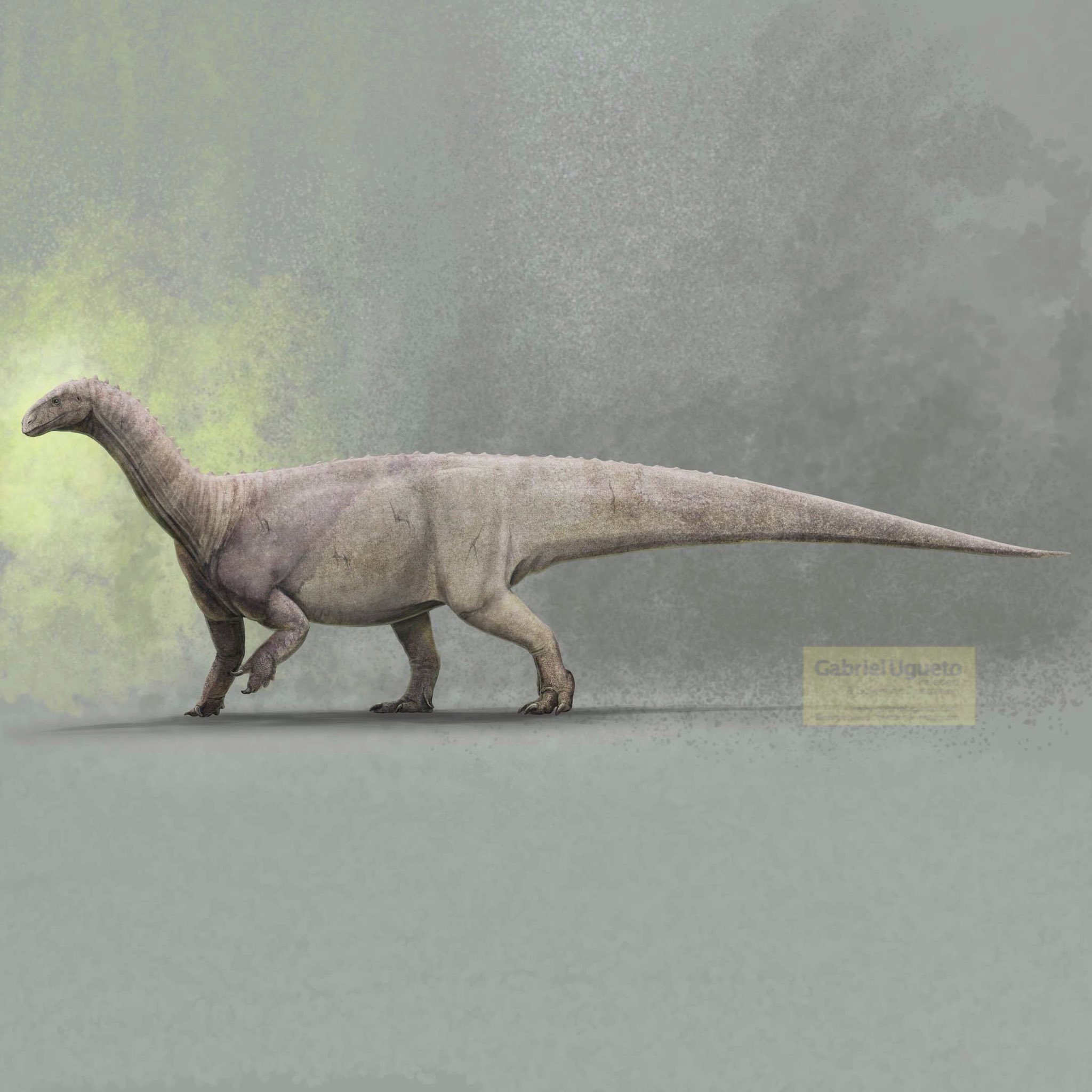

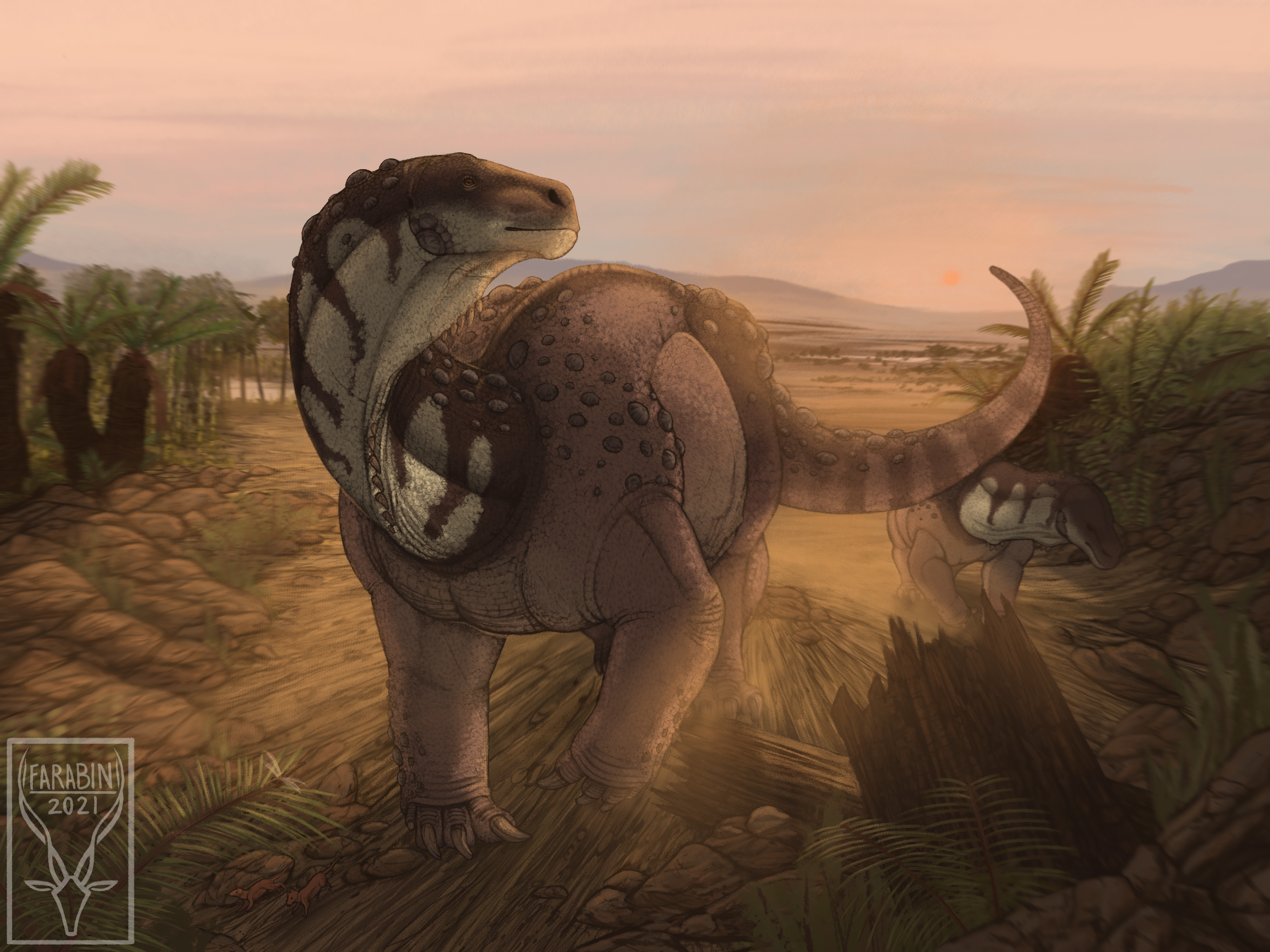

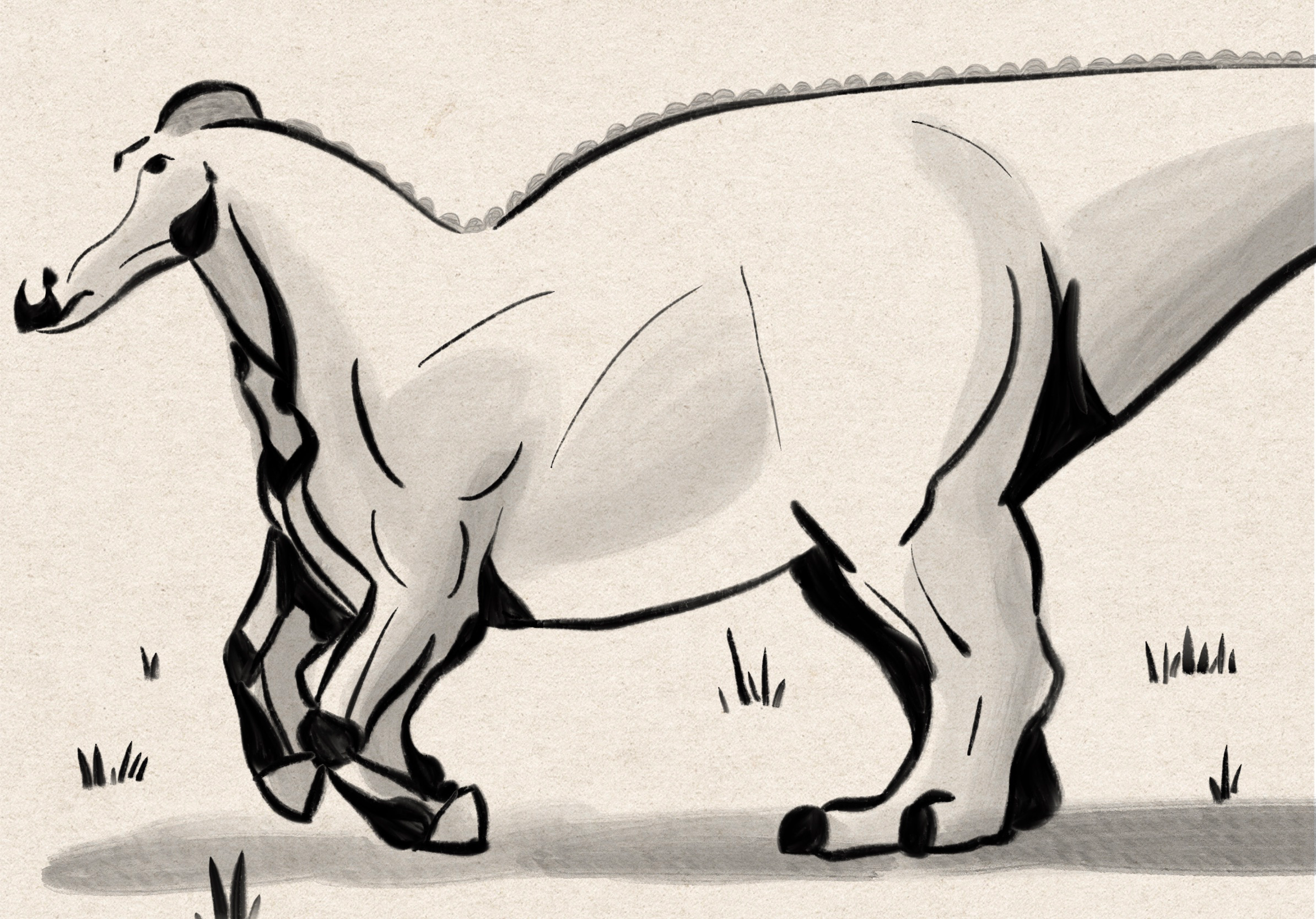

Above: Ledumahadi, whose name means “giant thunderclap at dawn”.

Lessemsaurids have always appeared to me to share similarities with bad paleoart of gravisaurian sauropods. Many of the mistakes that are common in media depictions of sauropods, such as visible front toes, bent, non-columnar elbows, and plantigrade stance in front and digitigrade in back like a dog, are actual traits that lessemsaurids had in real life. If movies would stop calling things “Apatosaurus” and “Brontosaurus”, maybe paleo nerds could pacify themselves by labeling them undescribed lessemsaurids.

Sauropods were some of the earliest dinosaurs to find widespread success. In the Early Jurassic, theropods, or meat-eating dinosaurs, were just beginning to reach apex predator status with animals like the horse-sized Dilophosaurus (much larger than the one in Jurassic Park), having previously taken a backseat to terrestrial croc relatives during most of the Triassic. And none of the famous ornithischian plant-eating dinosaur groups had arisen yet; ceratopsians (horn-faced dinosaurs like Triceratops), pachycephalosaurs (dome-headed dinosaurs), and hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) would not appear until the Cretaceous, 50 million years after Ledumahadi went extinct. The first ornithischians to achieve large sizes would be the stegosaurs, in the Middle Jurassic, but during the reign of the lessemsaurids, the ancestors of stegosaurs were still tiny, 10-kilogram bipeds like Scutellosaurus.

It may have been that it was the lessemsaurids’ lack of weight-bearing adaptations that caused their downfall. Gravisaurian sauropods, with their specialized columnar limbs, had a much larger ceiling on how big they could get, and gravisaurians at comparable sizes to lessemsaurids may have been simply better at moving around. It’s a recurring phenomenon that after a mass extinction takes out the previous ecosystem’s large-bodied animals, the ones that achieve large sizes first after the extinction do so by being hasty, and are later replaced by animals with a more comprehensive suite of adaptations. Other examples include the uintatheres and pantodonts, which rushed to fill large-herbivore niches after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs, but were later replaced by rhinos and bears, respectively.

What’s the purpose of evolving such large body sizes? As long as the environment will support it, it can be advantageous for a few reasons. Large animals have fewer predators (though sauropods, being r-strategists, meaning they laid many eggs and invested little effort into parental care, would have been picked off by predators in the dozens as youngsters) and can traverse greater distances, which is important if food sources are distributed across wide regions. They can also migrate long distances more easily, so are better able to take advantage of seasonal food sources. Large animals are also more energy-efficient, requiring less food relative to body weight than small animals since they dissipate less heat and generate more heat, due to the square-cube law. I’ve discussed all these aspects in more detail in my previous posts about thermoregulation and the physics of the very large and very small.

Edmontosaurines

At the other end of the Mesozoic, at the peak of dinosaur diversity and just before the asteroid impact, another group of non-avian dinosaurs tipped the anachronistic scales. The group of “duck-billed” dinosaurs known from North America and Asia during the latest Cretaceous known as edmontosaurines were large quadrupeds with skinny, hoof-like front legs and three-toed, digitigrade back legs–hardly a setup conducive to being truly massive. The best-known genus is Edmontosaurus, which had large oval scales on its neck and a fleshy cock’s comb on its head, as well as hoof-like nails on its front feet; we know all this because of exquisitely-preserved mummies!

One of the two species of Edmontosaurus could reach weights of up to nine tonnes, but the true giant in this group was Shantungosaurus, Edmontosaurus’s Asian cousin. While we don’t have quite as comprehensive fossil remains of this animal, it is still known a decent amount of skeletal material from five individuals, providing a relatively confident weight estimate of sixteen tonnes. Other than its size, it was seemingly similar to Edmontosaurus in appearance and lifestyle: a sharp, vegetation-cropping beak at the front of its mouth followed by 1500 tiny teeth in the back of its mouth that were fused into a file-like chewing surface shows that it was a grazer that would have fed on roughage. Instead of a noise-making head crest like the other branch of the hadrosaur family tree, the lambeosaurs, Shantungosaurus may have had a noise-making inflatable nose sac. Noise making must have been very important to these social dinosaurs!

Shantungosaurus had a body plan that much more closely resembled that of a cursorial creature, with a high cursorial limb proportion score, though not as high as the smaller members of its group. It descended from a lineage of swift, quadrupedal runners, but jettisoned some of that cursoriality, moving closer to graviportality. While it’s not known for sure why Shantungosaurus was so enormous, my hypothesis is that since Asia was much wider and more seasonal than North America (which was still partially divided by the Western Interior Seaway into the two continents of Laramidia and Appalachia at the time), hadrosaurs there could benefit more from the aforementioned benefits of long-distance travel provided by larger size. Or perhaps it had something to do with predator-prey interactions: in North America, Tyrannosaurus was a ten-tonne-plus terror that perhaps could be outrun but not defeated, while Tarbosaurus, Tyrannosaurus’s Asian cousin, was only around four tonnes and would not have challenged an adult Shantungosaurus. But if the predators are influencing the prey species’ body sizes, it must work the other way around as well, leading to a chicken-and-egg conundrum. Was Shantungosaurus big because Tarbosaurus was small, or vice versa? And whichever one was the cause would require an external cause to explain.

A parallel story in mammals

While I mainly wanted to talk about dinosaurs in this post, I’d be remiss not to mention the other land animals that have surpassed modern elephant sizes. Like sauropods but playing for smaller stakes, elephants as a group tend to produce a lot of really big species, probably due to their graviportal adaptations (columnar limbs, semi-plantigrade stance, flappy heat-dissipating ears). The extinct elephant species Palaeoloxodon namadicus, from Pleistocene India, may have weighed up to 20 tonnes, and the steppe mammoth from Pleistocene Russia may have weighed up to 14 tonnes.

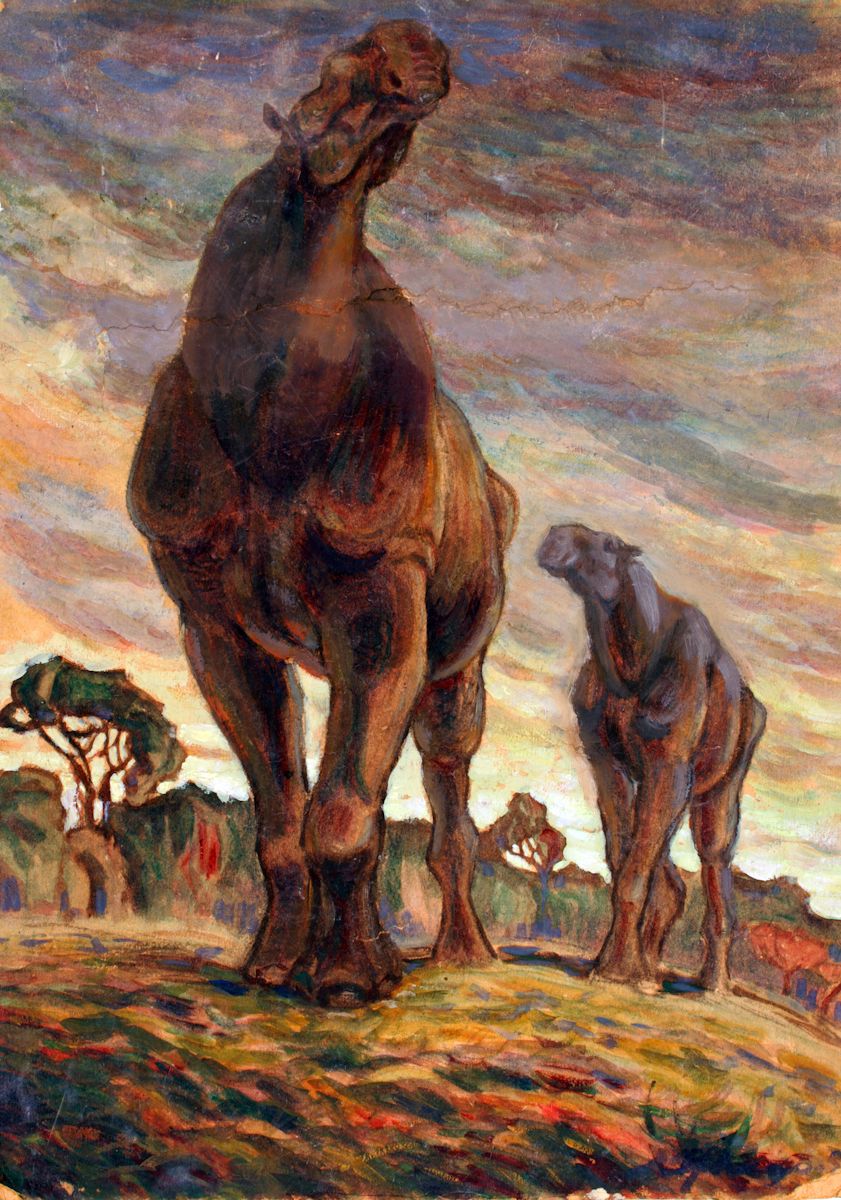

However, sort of similarly to lessemsaurids and edmontosaurines, there’s one giant mammal that lacked those adaptations but rivaled the largest elephants in size: Paraceratherium, the giant hornless rhino (also sometimes known as Indricotherium).

It was very slender compared to an elephant, and had a high cursorial limb proportion score, with a short, strongly angled humerus and femur. It probably didn’t weigh quite as much as Palaeoloxodon, with modern estimates putting Paraceratherium at eleven or twelve tonnes, but it stood head and shoulders taller, making it the tallest land mammal ever. How’s that for an overly specific category?

Conclusion

Interestingly, these giant mammals and non-gravisaurian dinosaurs provide case studies of what would happen when animals trying to get large face different limiting factors. Lessemsaurids and edmontosaurines had the egg-laying and the efficient lungs and bones, but were limited in size due to non-graviportal limbs. Elephants have graviportal limbs but give live birth and lack efficient breathing and skeletal systems. Gravisaurian sauropods had all the requisite traits, and thus were able to wildly surpass all other terrestrial animal groups’ upper limits. Furthermore, it seems like perhaps the graviportal adaptations are the more important limiting factor, since each group that produced a gigantic species that lacked such adaptations did it only once each, while the groups with graviportal adaptations did it many times over, making size a defining feature of the whole group.

Image Credits

Water deer skeleton Elephant skeleton Melanorosaurus Kholumolumo Ledumahadi Edmontosaurus Paraceratherium