Are you intimidated by the overly-detailed phylogenetic trees and endless jargon you find on Wikipedia when you’re trying to learn about a specific dinosaur? Are you overwhelmed by the sheer number of genera and do you struggle to figure out which groups are actually important? Or do you just want to get familiar with dinosaurs without much overhead? Then this is the post for you! Here I will go over the major groups within Dinosauria and how they’re related to one another.

Dinosauria

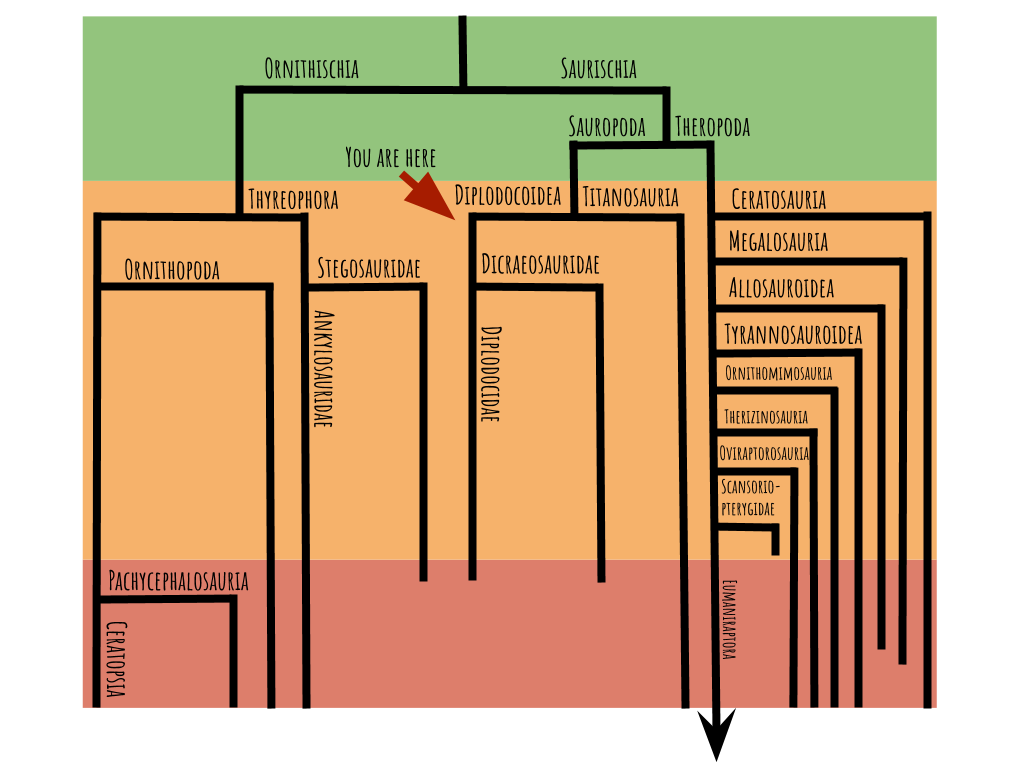

This clade is usually defined nowadays as the last common ancestor between Triceratops and modern birds, and all its descendants. It was historically defined as the last common ancestor of Megalosaurus and Iguanodon and all its descendants, which is just a different way of describing the same group. This group includes sauropods (the long-necked dinosaurs like Apatosaurus), theropods (the bipedal carnivorous dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus and also birds), thyreophorans (the armored dinosaurs), ornithopods (the duck-billed dinosaurs), ceratopsians (the horned dinosaurs), and some other, less well-known groups. Pterosaurs (Mesozoic flying reptiles) are closely related to dinosaurs but are not dinosaurs.

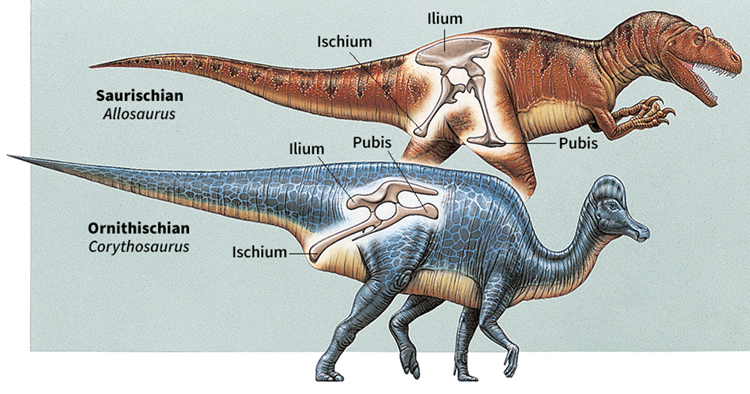

Dinosaurs all belong to one of two groups: Saurischia (meaning “reptile-hipped”) and Ornithischia (meaning “bird-hipped”). Sauropods and theropods fall under Saurischia (yes, confusingly birds are not in the bird-hipped group, but are in the reptile-hipped group) while the rest fall under Ornithischia.

The hip distinction is a little obscure at first sight, but this is what it’s about: of the three main hip bones, saurischians have one on top, one pointing forward, and one pointing backward, while ornithischians have one on top and two pointing backward. This makes room for the larger gut required to effectively digest plants (meat, lacking tough cell walls, is much easier to digest). The reason this difference is important is that it’s a useful hallmark for identifying remains, and it’s almost always consistent within each group.

Note: The new discovery of Chilesaurus and some statistical studies of skeletal characteristics have cast some doubt on the validity of the traditional Saurischia / Ornithischia split in favor of a new Saurischia / Ornithoscelida structure. Saurischia then only would include sauropods and some early dinosaurs like herrerasaurs, while Ornithoscelida would include theropods (including birds) and everything that’s currently within Ornithischia. Here I’m sticking to the traditional Saurischia / Ornithischia structure because the new structure is controversial and not universally agreed-upon yet, but I may change this in the future if more evidence surfaces that points one way or the other.

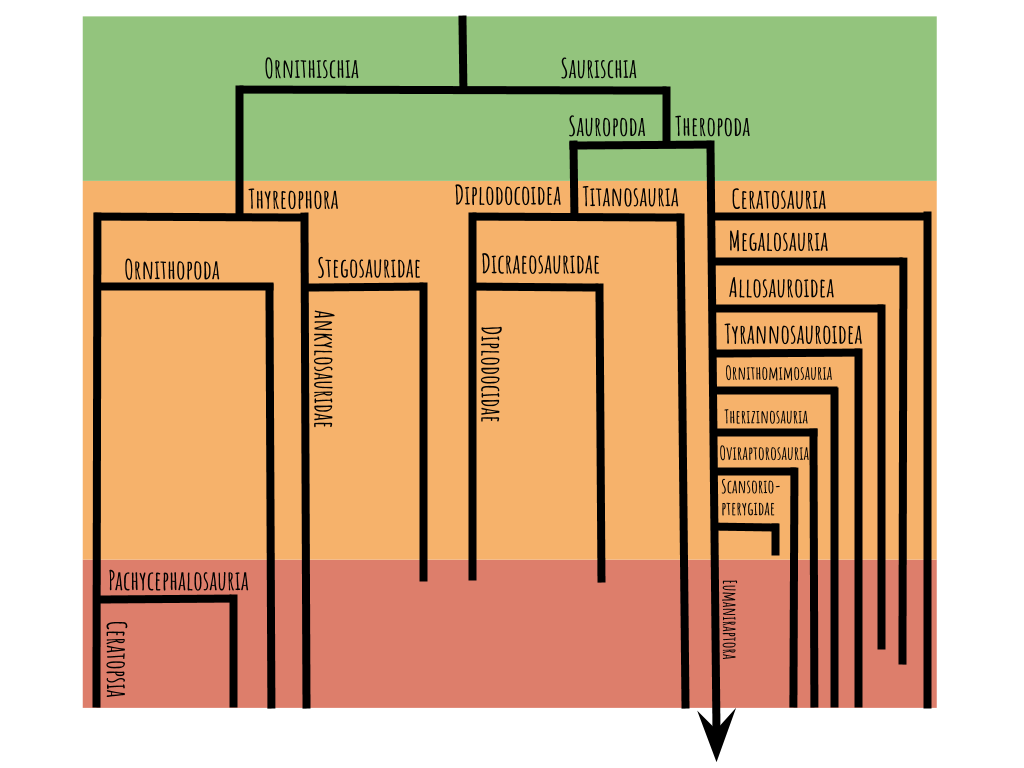

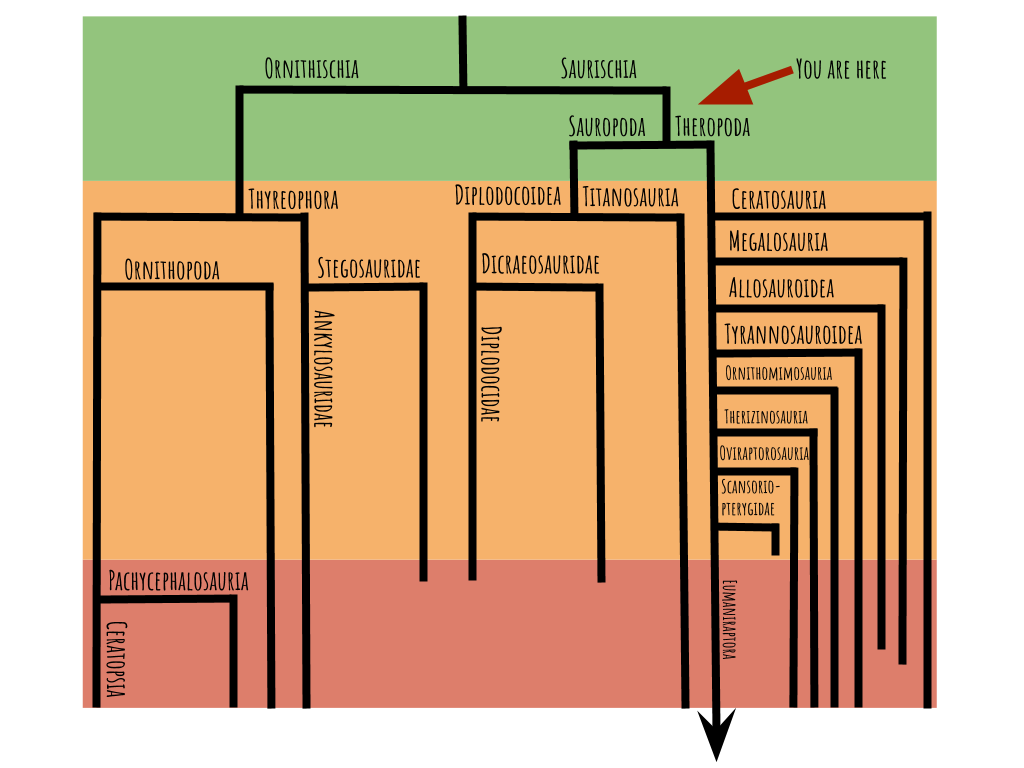

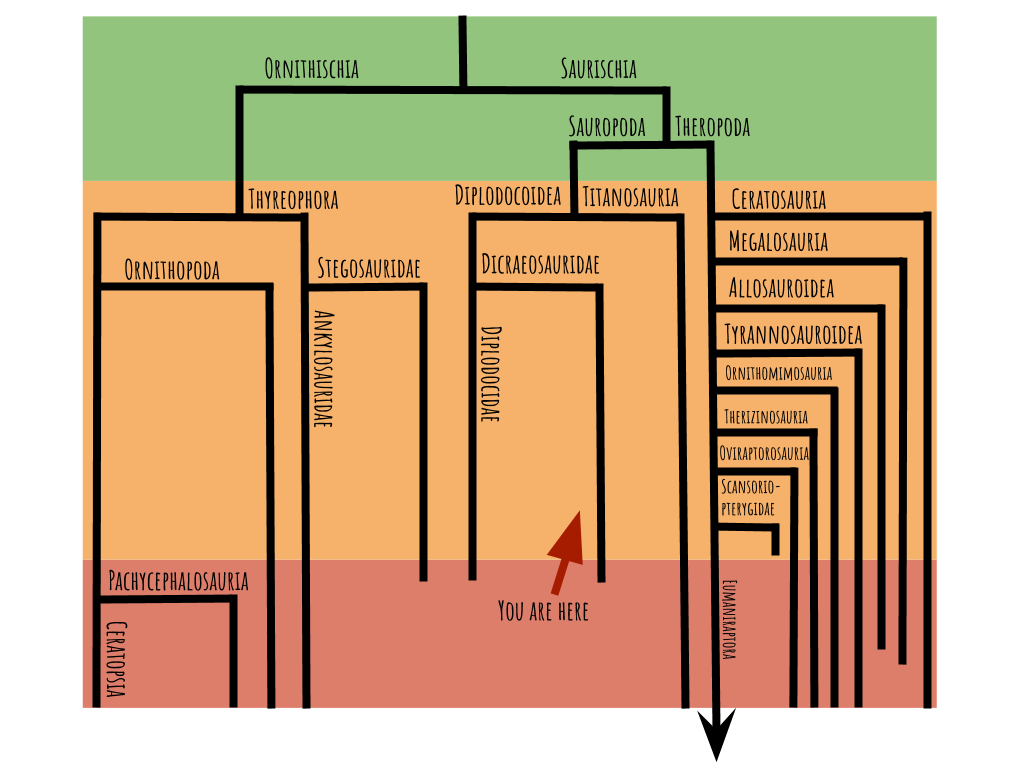

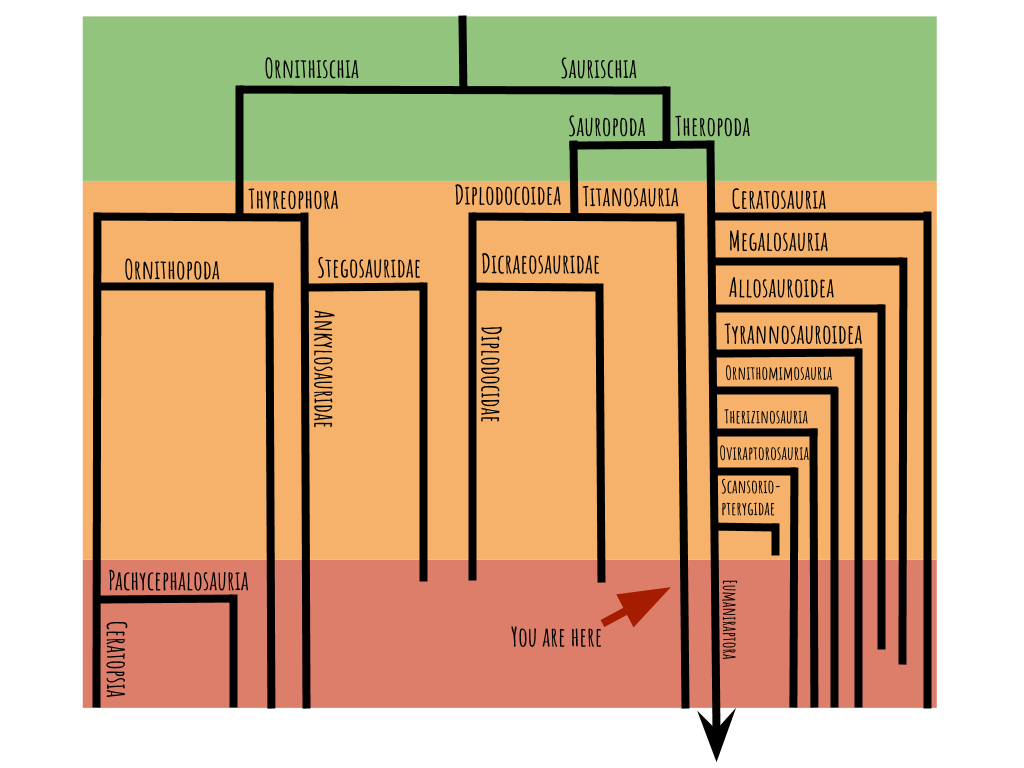

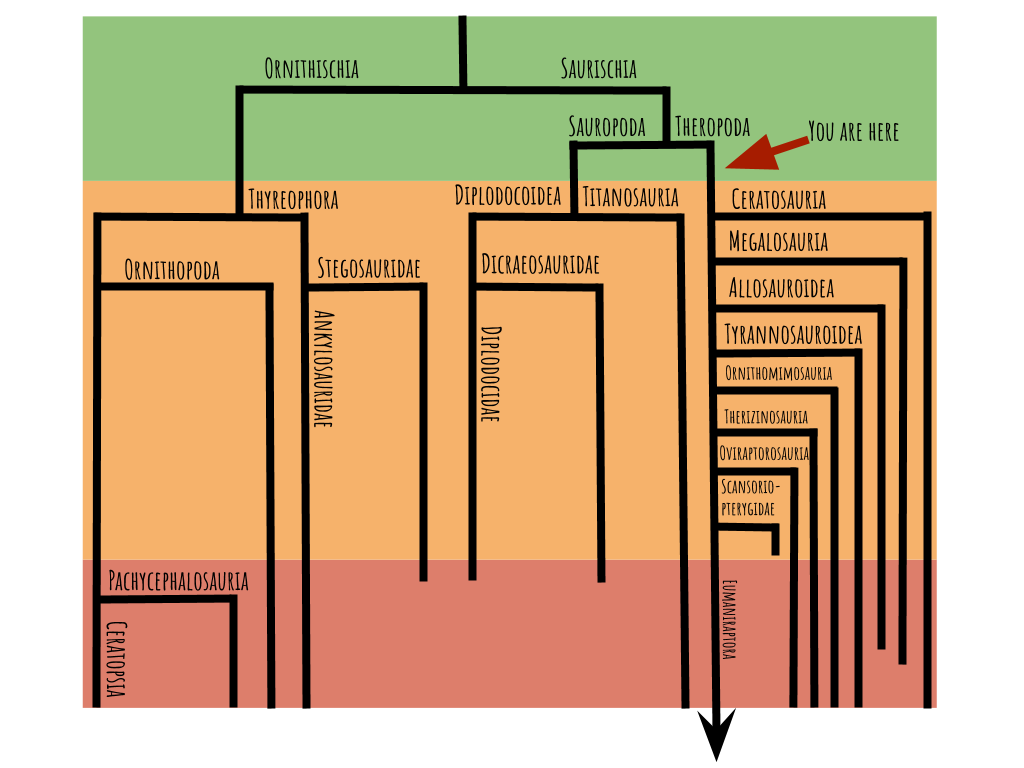

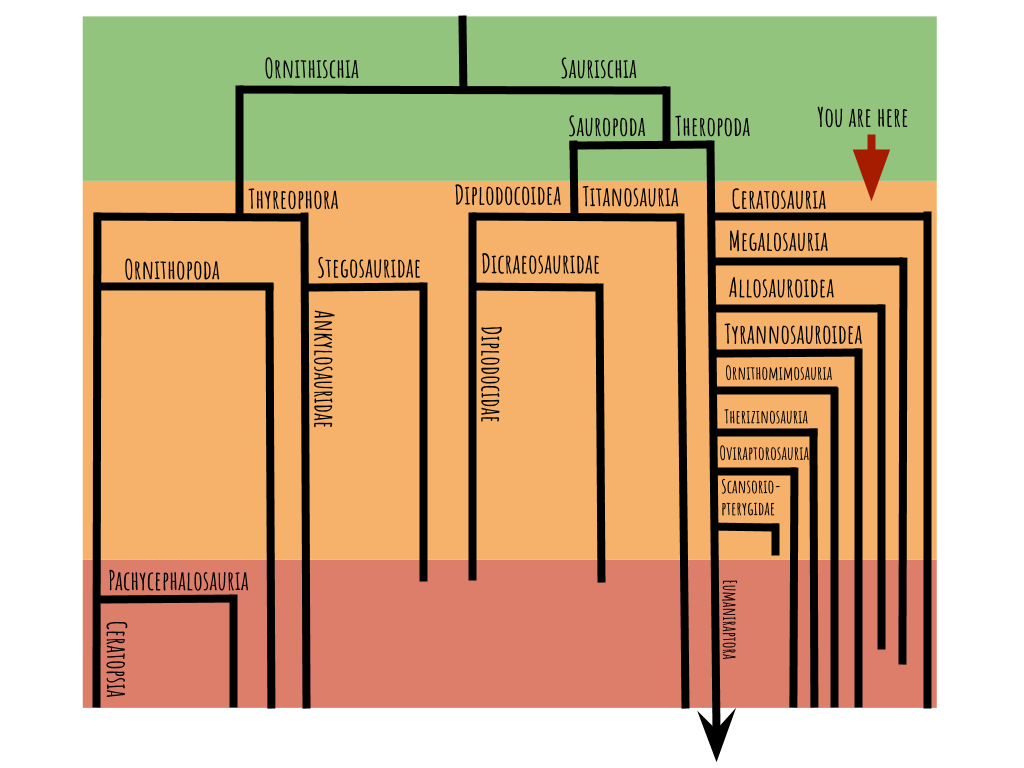

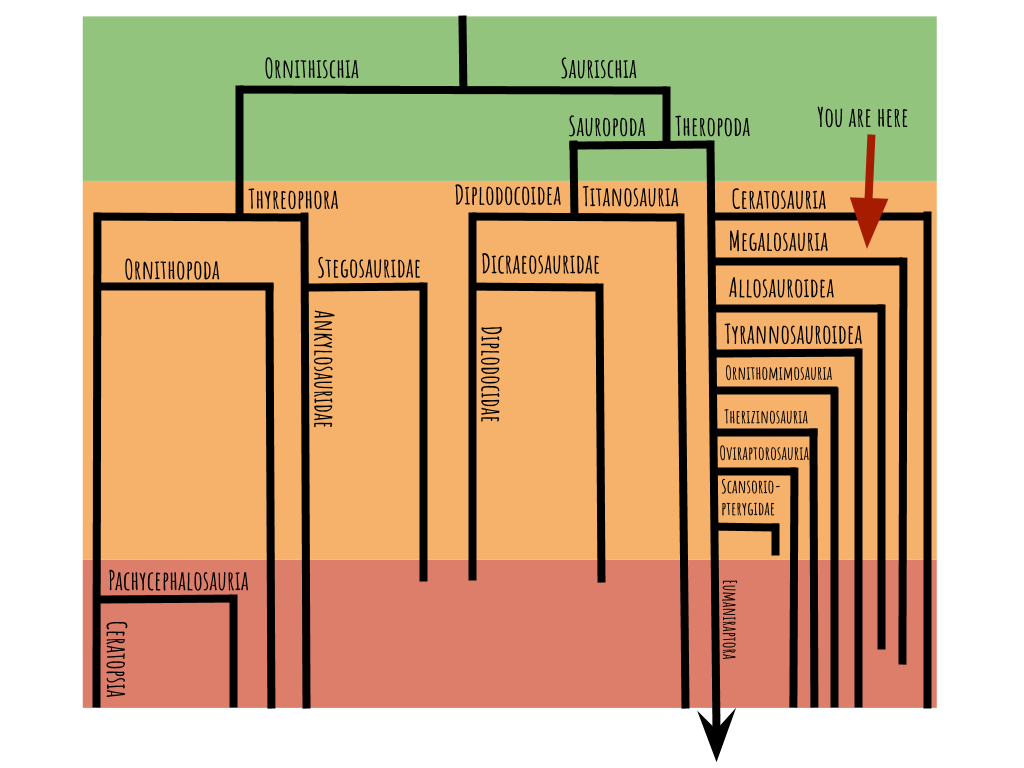

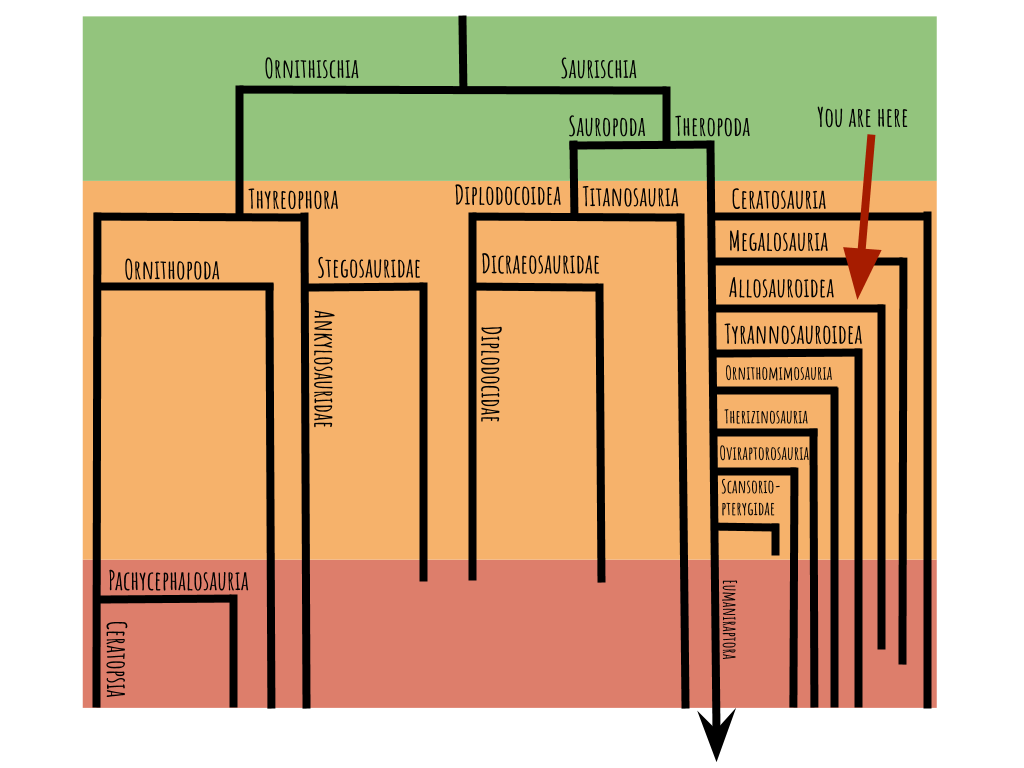

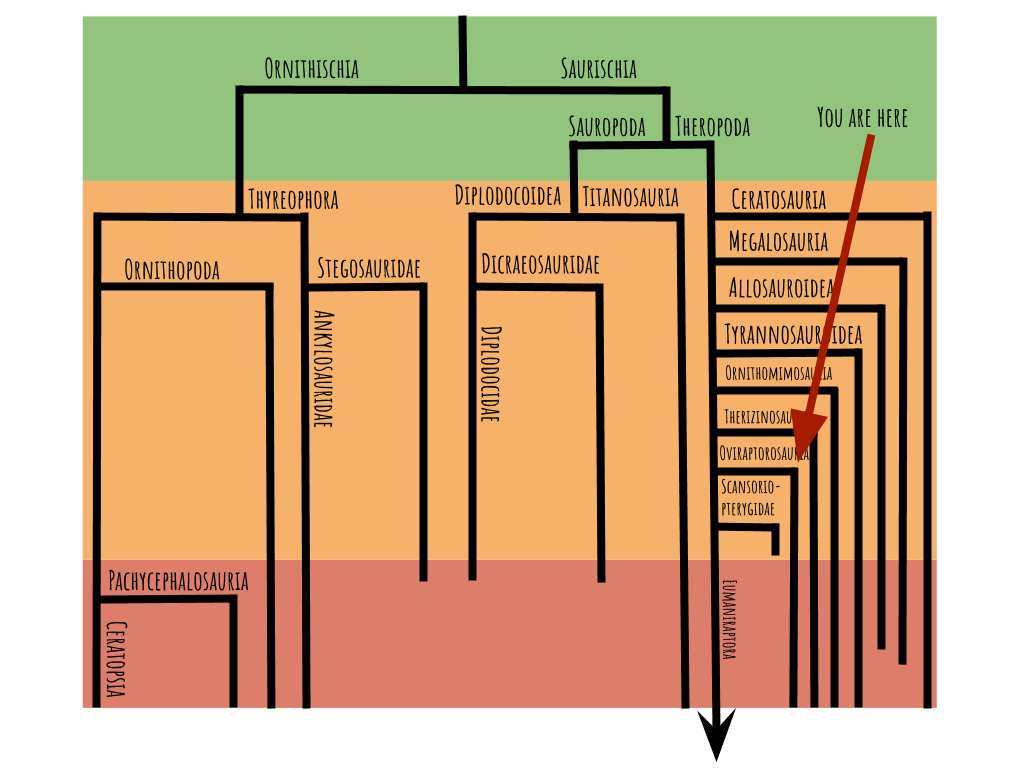

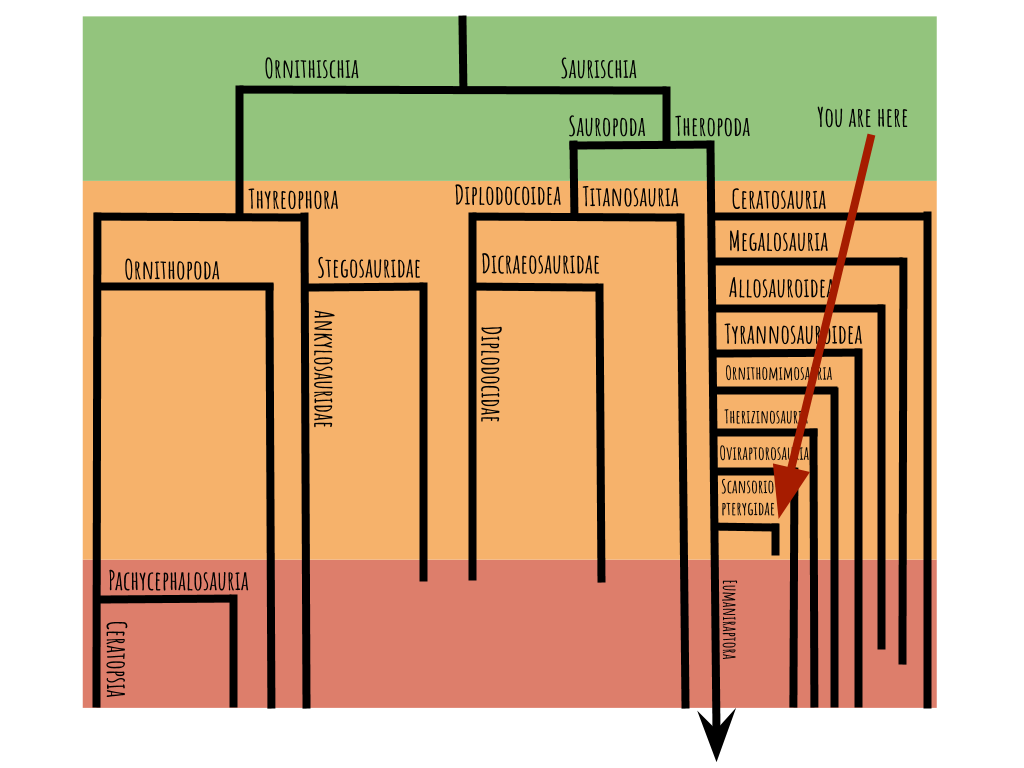

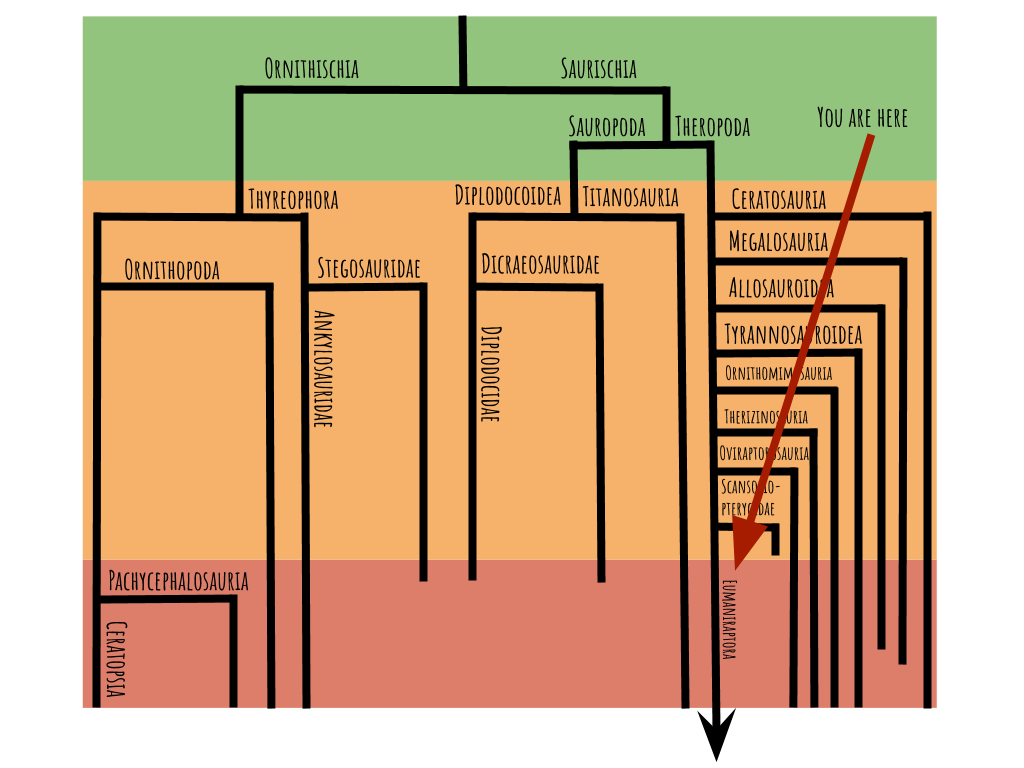

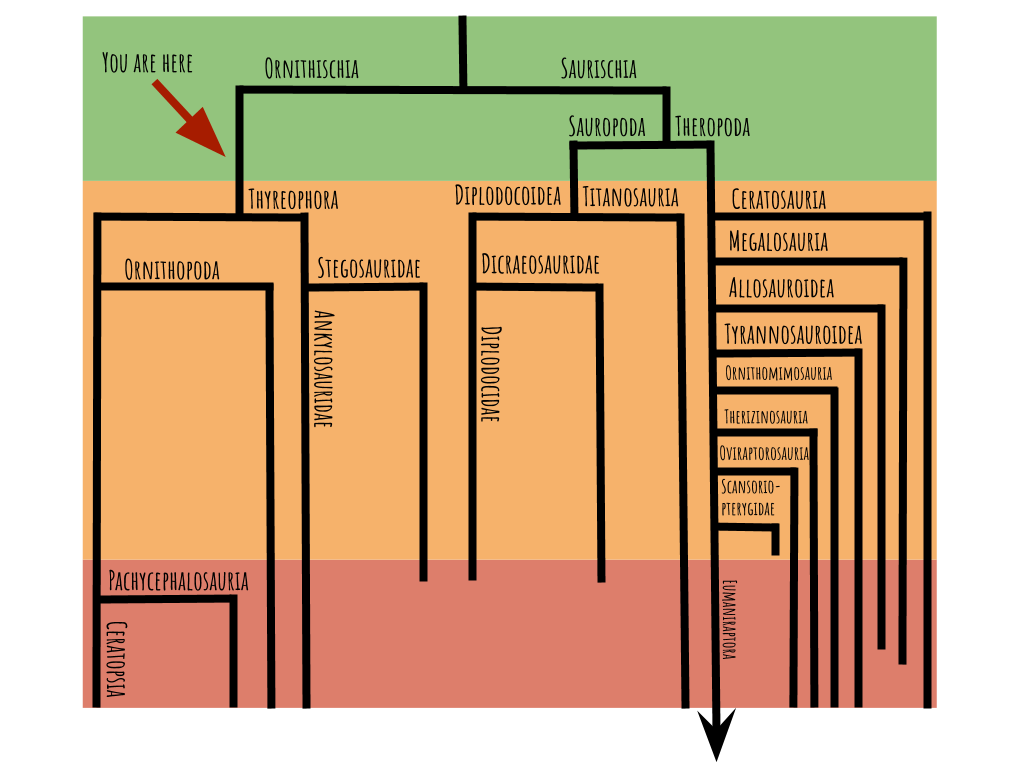

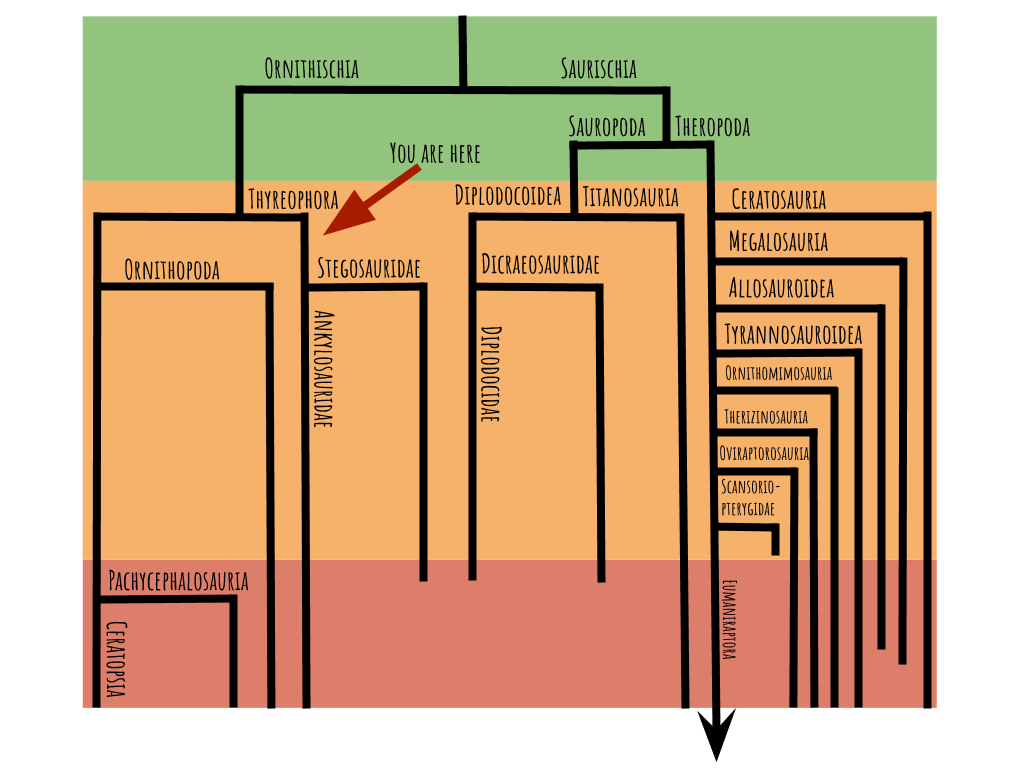

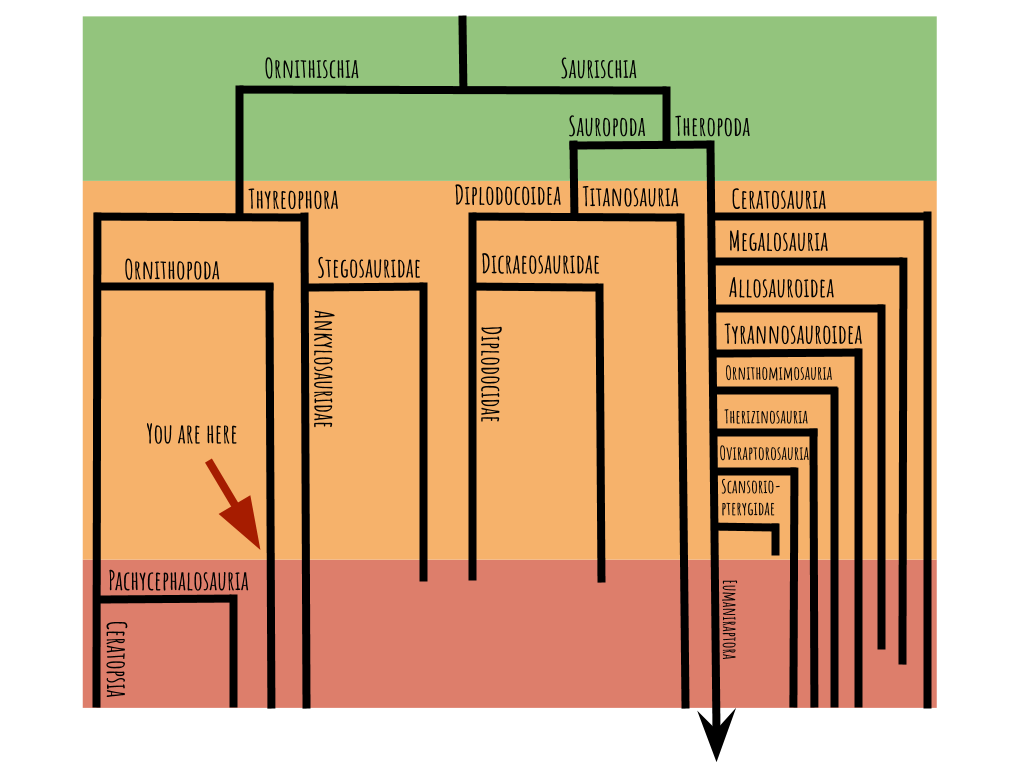

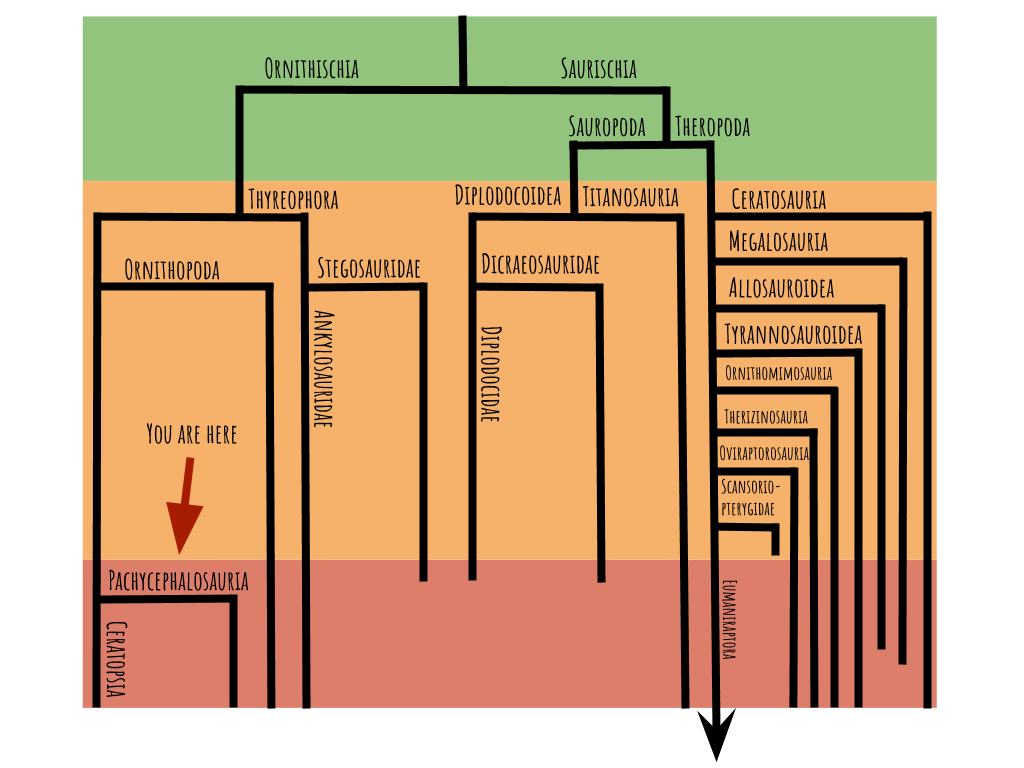

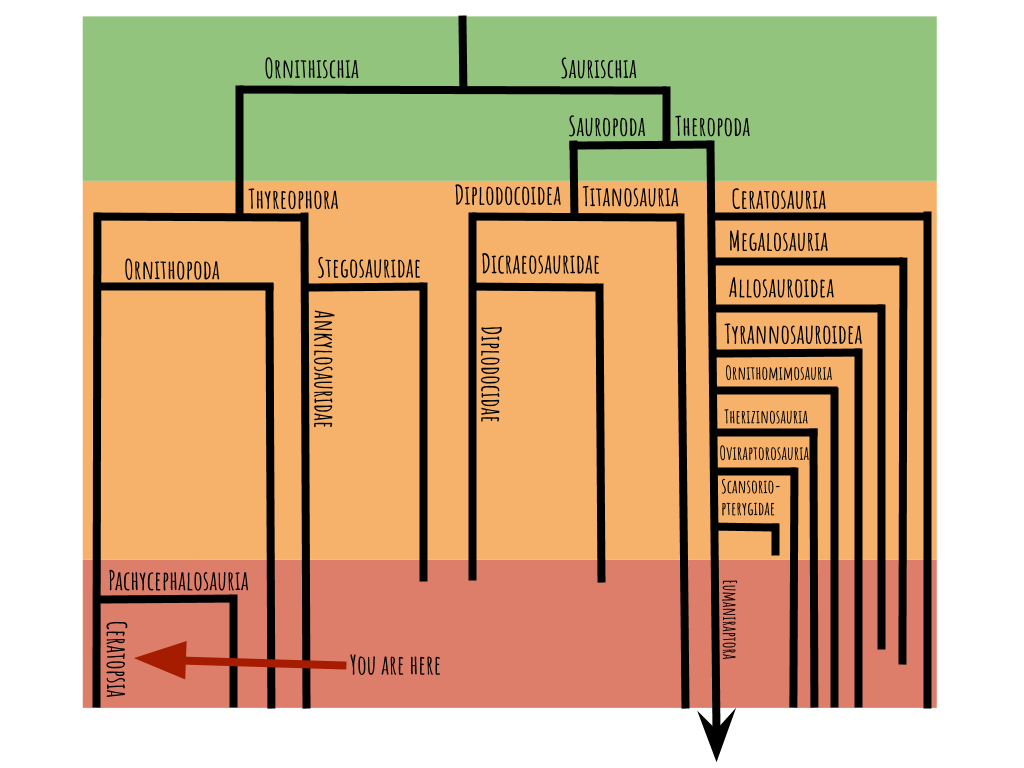

Here is a simplified dinosaur family tree:

The colored backgrounds represent the Triassic (green), Jurassic (orange), and Cretaceous (red), not to scale. Where a branch ends, it means that line has gone extinct. Note how all the branches go extinct at the end of the Cretaceous except Eumaniraptora–that’s the group that includes birds. In this post, we’ll take a quick look at each branch and go over who they’re related to, some general characteristics of that group, and some examples with pictures. Note that this family tree is quite simplified, and there are many dinosaurs that fall outside of the groups shown.

Saurischia

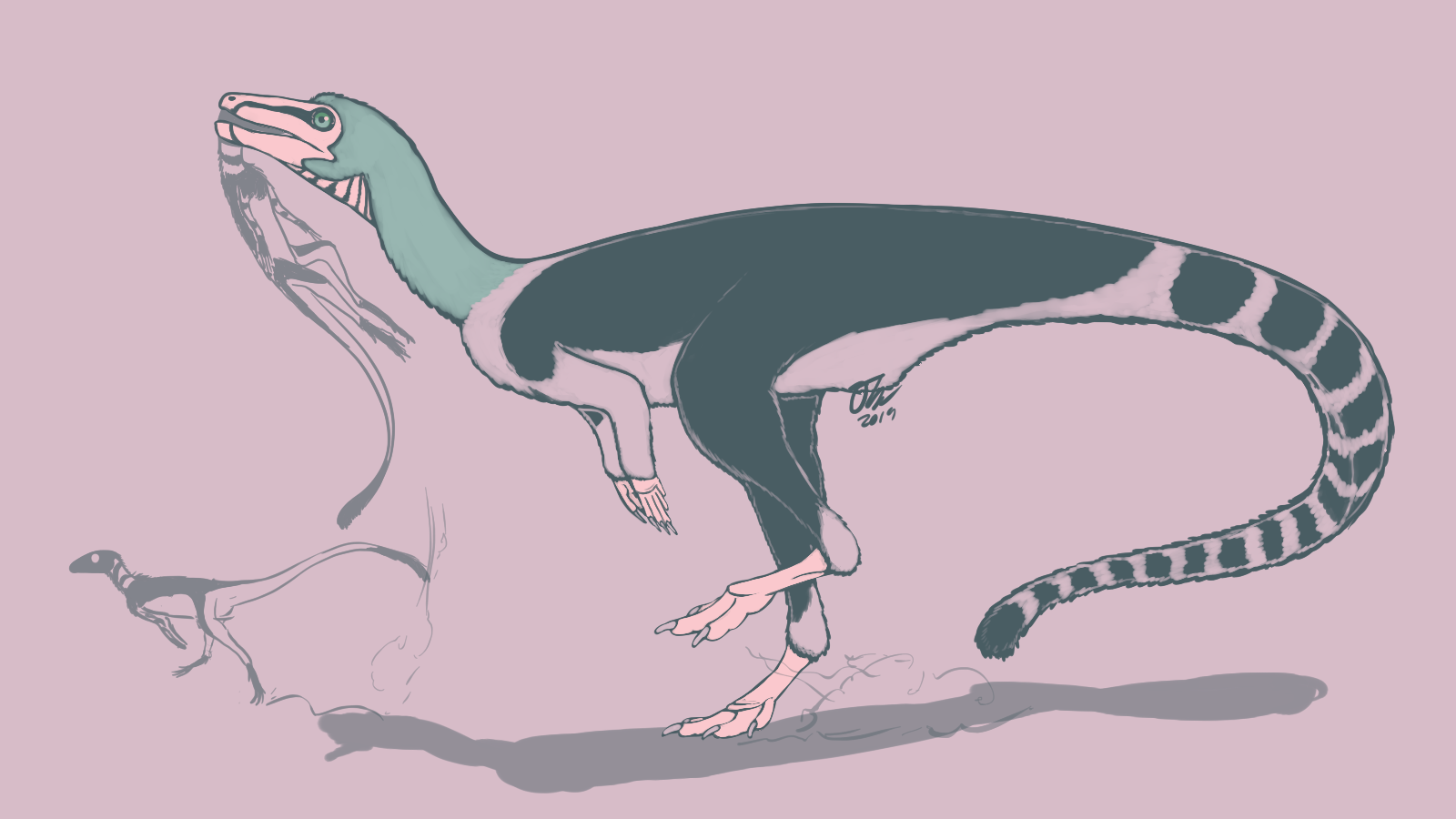

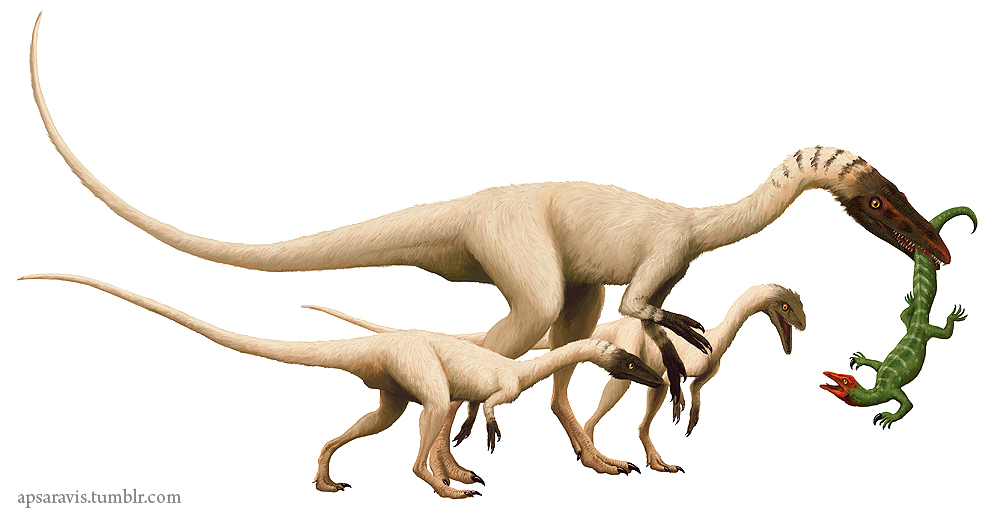

Saurischia includes the sauropods and theropods (which includes modern birds). They started out in the Triassic period looking something like this:

Above: Buriolestes, an early carnivorous sauropodomorph that lived soon after the theropod line and the sauropod line split from each other.

Then each group became more specialized–theropods for hunting and sauropods for high-browsing–until by the end of the Triassic, they looked something like this:

Coelophysis, a well-known Late Triassic theropod dinosaur.

Plateosaurus, a Late Triassic omnivorous sauropodomorph. Early sauropod relatives were bipedal, and became quadrupedal later on.

In the Jurassic and Cretaceous, theropods and sauropods each split into further, more specialized groups, which we’ll explore next.

Sauropoda

In the Jurassic, sauropods really hit their stride and became hugely diverse and successful (and also just huge). There are two main flavors of true sauropod: the gigantic vertical-necked titanosaurs and the more slender, whip-tailed diplodocoids. Titanosaurs were the largest terrestrial creatures ever, and were able to grow to such great sizes due to a few key adaptations.

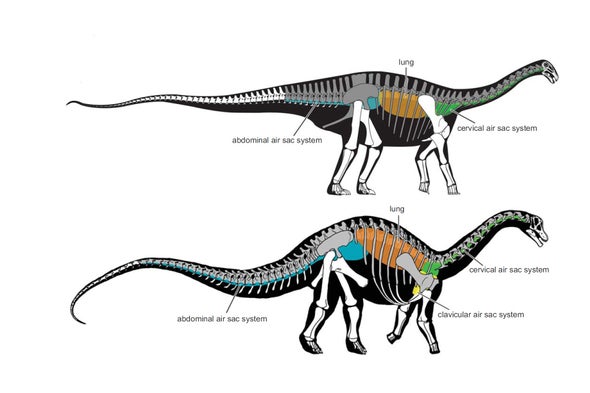

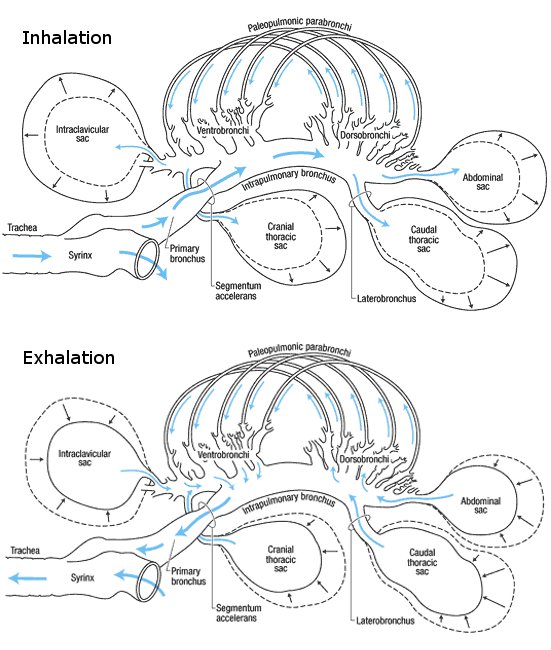

1) Air sacs. Like modern birds, sauropods had hollow bones with air sacs inside, as well as air sacs interspersed all over the place within their bodies. These made it so that they were way lighter than they would be otherwise.

2) Flow-through lungs. Also like modern birds, sauropods had a super-efficient way of breathing that utilized all those air sacs. Rather than the air coming in, hitting a dead end, and then going back the way it came, which is how we breathe, the air went in a loop, so sauropods could exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide much more efficiently, and their huge bodies could get the massive amounts of oxygen they required.

Above: A bird lung. Sauropods and theropods also had this style of ridiculously complicated lung.

3) Columnar legs. Sauropods had crazy-specialized graviportal front legs for bearing all that weight. They had no visible toes, instead walking on a hard horseshoe of bone. Without this, there’s a limit to how big you can get even if you have air sacs and flow-through lungs (Ledumahadi and Shantungosaurus, the largest dinosaurs that didn’t have columnar legs, could get to about 16 tonnes). With this adaptation, the largest titanosaurs reached up to 76 tonnes!

4) Egg laying. As animals get larger, the gestation period required to give live birth gets longer, and the huge fetus gets inconvenient to lug around for such a long time. Sauropods sidestepped this issue by continuing to lay lots of tiny eggs, most of which would not make it to adulthood, and investing no parental care.

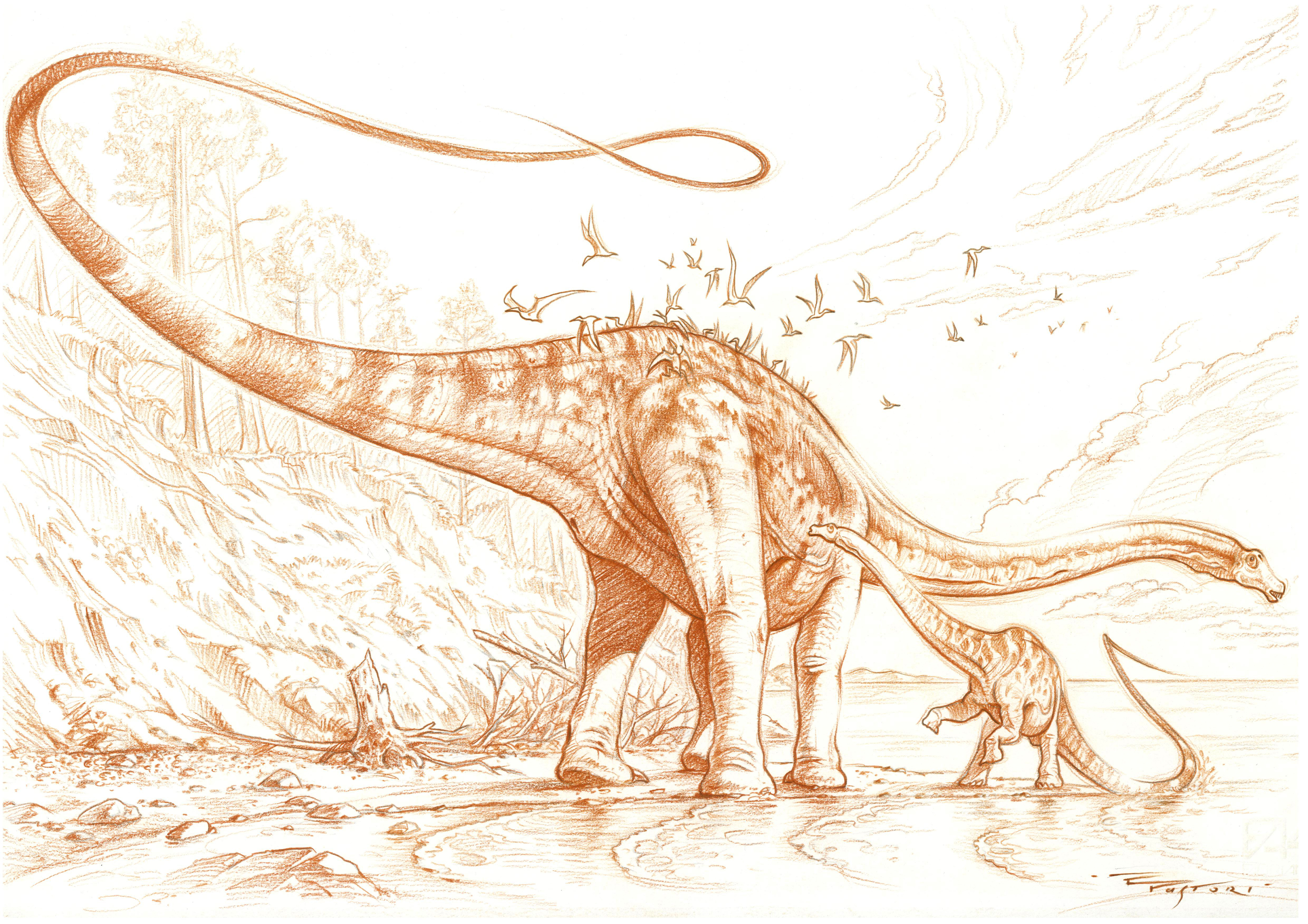

Diplodocoidea

Diplodocoids (meaning “double-beamed”) were one of the two main types of sauropod, most abundant and diverse in the Late Jurassic. Many of them would have been “branch strippers,” using their long faces to grasp the base of a branch and pulling back their necks to eat the leaves. Their long, spiny tails would have scared off would-be attackers, either through superior melee range or by making whip-crack sounds. Famous diplodocoids include Diplodocus, Apatosaurus, and Brontosaurus.

Above: a slightly outdated depiction of Diplodocus and baby. Notice the long, sort of horselike face characteristic of Diplodocoidea. Newer evidence points to the nostrils being lower on the snout rather than up on the forehead, and the presence of spikes along the back and tail.

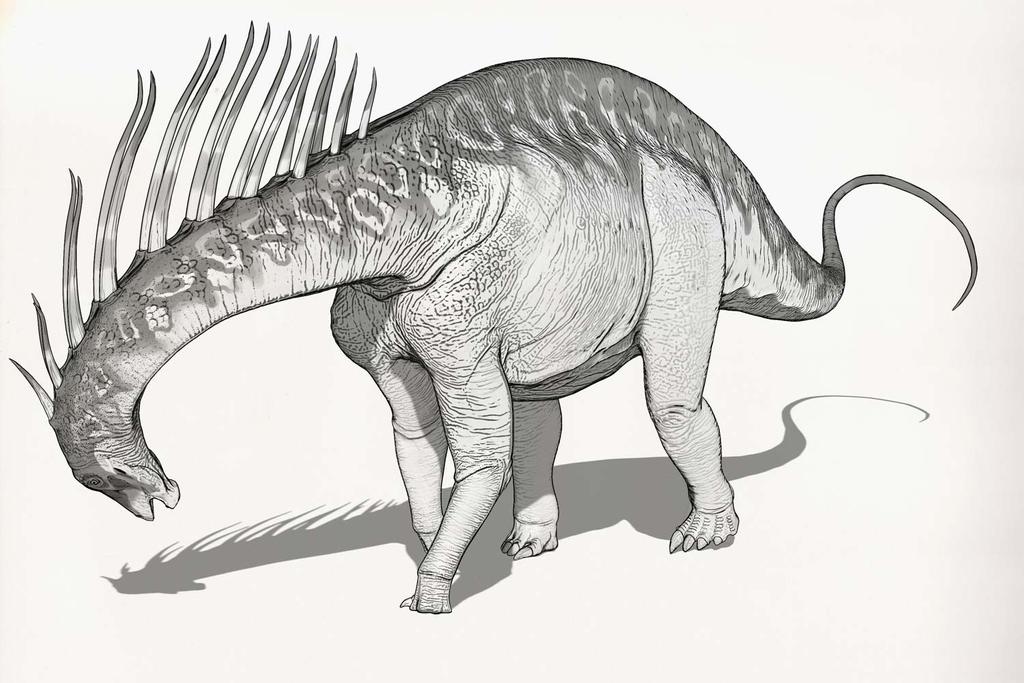

Dicraeosauridae

A subset of Diplodocoidea, dicraeosaurids (meaning “bifurcated reptile”) are an unusual family of relatively small and short-necked sauropod, some of which had two rows of crazy horns down their necks. These could’ve been for display or to ward off predators while their necks were lowered to feed, and were probably keratinized (covered in keratin, like a beak, horn, or fingernail). They probably fed by standing in one place and using their low, horizontal necks to eat bushes and shrubs (grass didn’t exist yet at that time) within their wide radius. Famous members include Amargasaurus, Dicraeosaurus, and Bajadasaurus.

Above: Amargasaurus, a dicraeosaurid from Early Cretaceous Argentina. Argentina is famous for its really cool sauropods.

Titanosauria

The other main type of sauropod, titanosaurs, were the top-browsers of the Cretaceous, and included the largest terrestrial animals ever.

Giraffatitan, a Late Jurassic titanosaur. Because of osteological correlates (texture of bone that indicates what sort of tissue overlaid it in life), there’s reason to believe that titanosaurs had a lot of soft tissue on their heads and faces, but we don’t yet know what kind. Some artists have taken this to an extreme.

A somewhat more conservative reconstruction of Argentinosaurus, a Late Cretaceous titanosaur and one of the heaviest terrestrial animals ever.

Theropoda

Theropods are one of the most diverse groups of dinosaurs, representing many varying shapes, sizes, and lifestyles. They were ancestrally carnivorous and proto-feathery, but some groups became secondarily herbivorous or lost their feathers later on. Some famous examples of theropods include Tyrannosaurus, Spinosaurus, Velociraptor, Oviraptor, and all modern birds.

Ceratosauria

The first large family of theropods to branch off the bird line were the ceratosaurs, meaning “horn reptile”. These were large carnivores that often had keratinous horns and bosses on their heads and faces. Famous members include Ceratosaurus and the more derived abelisaurs, including Carnotaurus and Majungasaurus.

Carnotaurus (meaning “meat bull”), also known as “The Mouth With Legs,” an abelisaur with a short face, bull-like horns, and very silly arms.

Ceratosaurs filled a similar niche to the big cats of today: their jaws didn’t bite with a lot of force, but they could resist a lot of twisting, indicating that they bit once and then held on until the prey was subdued.

Megalosauria

The next major theropod group to branch off the bird lineage were the megalosaurs, meaning “great reptile”. Megalosaurus itself, a generic large carnivore, was the first non-avian dinosaur to be validly named, in 1824. It predates the term “dinosaur” by 17 years! The more derived members of this group, the spinosaurs, were much more interesting:

Spinosaurus, the record holder for largest theropod ever. Spinosaurs had long, alligator-like faces good for catching fish, and some had huge sails, good for who-knows-what (probably display). Famous members include Spinosaurus, Baryonyx, Suchomimus, and Irritator.

Allosauroidea

Moving along, the next group to branch off the bird lineage were the allosauroids (meaning “other reptile”), including the famous Allosaurus and the later carcharodontosaurs (meaning “sharp tooth reptile”) like Carcharodontosaurus, Mapusaurus, and Giganotosaurus. Carcharodontosaurs had long faces and shark-like slicing teeth, indicating that they took prey down by biting over and over, like dogs.

Giganotosaurus, a giant carcharodontosaur that made headlines as “the one bigger than T. rex”. It’s only very slightly bigger.

Carcharodontosaurs were the dominant terrestrial predator throughout the Early Cretaceous until the more advanced giant tyrannosaurs arrived on the scene in the Late Cretaceous.

Tyrannosauroidea

Tyrannosaurs (meaning “tyrant reptile”) were the next to branch off. They had certain key adaptations that gave them an edge over other large carnivores at the time:

- Peg-like teeth. These super-strong teeth allowed tyrannosaurs to crush bone, like hyenas do today, to get at the nutritious marrow. They also helped them have a ridiculously powerful bite.

- Sharp senses. Based on the shape of tyrannosaurs’ brain cavity, we know that they had sharper eyes and noses than their predecessors, which allowed them to hunt more effectively.

- Increased smarts. Also based on brain cavity evidence, we know that tyrannosaurs could probably outsmart prey and competition more effectively than other giant theropods.

Ontogeny of Tyrannosaurus. Notice how the younger ones have long, skinny legs before they bulk out later in life.

Note: Did T. rex have feathers? Now we think they did not. Some large-bodied tyrannosaurs that lived in colder climates, like Yutyrannus, did have feathers, but from numerous fragmentary skin impressions from The King, there’s reason to believe Tyrannosaurus itself was completely scaly.

Ornithomimosauria

The next main group to branch is the first secondarily herbivorous or omnivorous group we’ll look at, the ornithomimosaurs (“bird mimic reptile”). They are notable for their resemblance to modern ostriches, and they probably filled the same niche. Many ornithomimosaurs even had toothless beaks. Famous members include Gallimimus, Struthiomimus, and Ornithomimus.

Struthiomimus, meaning “ostrich mimic”.

Therizinosauria

Therizinosaurs (meaning “rake reptile”) are the next branch, and one of the strangest. They were also secondarily herbivorous, and some of them also had beaks, but the feature that got them their name is their ridiculous claws. They were the pandas of the Cretaceous, using their claws to strip vegetation and defend themselves.

A speculative reconstruction of a very fluffy Therizinosaurus. This is probably inaccurate because Therizinosaurus was very large, but it’s very cute!

Oviraptorosauria

Another group of secondarily herbivorous or omnivorous theropods, the oviraptorosaurs (“egg thief reptile”) were quite birdlike, possibly filling the niche of a cassowary. Famous examples include Oviraptor, Anzu, and Gigantoraptor.

Oviraptor was originally named due to the first specimen being found next to a nest full of eggs, which it was thought to be caught in the act of stealing. However, it was later discovered that they were its own eggs, indicating that these dinosaurs and probably many others exhibited brooding behavior like modern birds.

Scansoriopterygidae

Scansoriopterygians (meaning “climbing wing”) were an unusual group of tiny paravians that glided using a totally different strategy than birds. Instead of using feathers as the flight surfaces, they had membranous wings like pterosaurs and bats, though the details of how the wings were supported differ between all three of those groups. The group has only been known since 2002, and the fact that they had membranous wings has only been known since 2015!

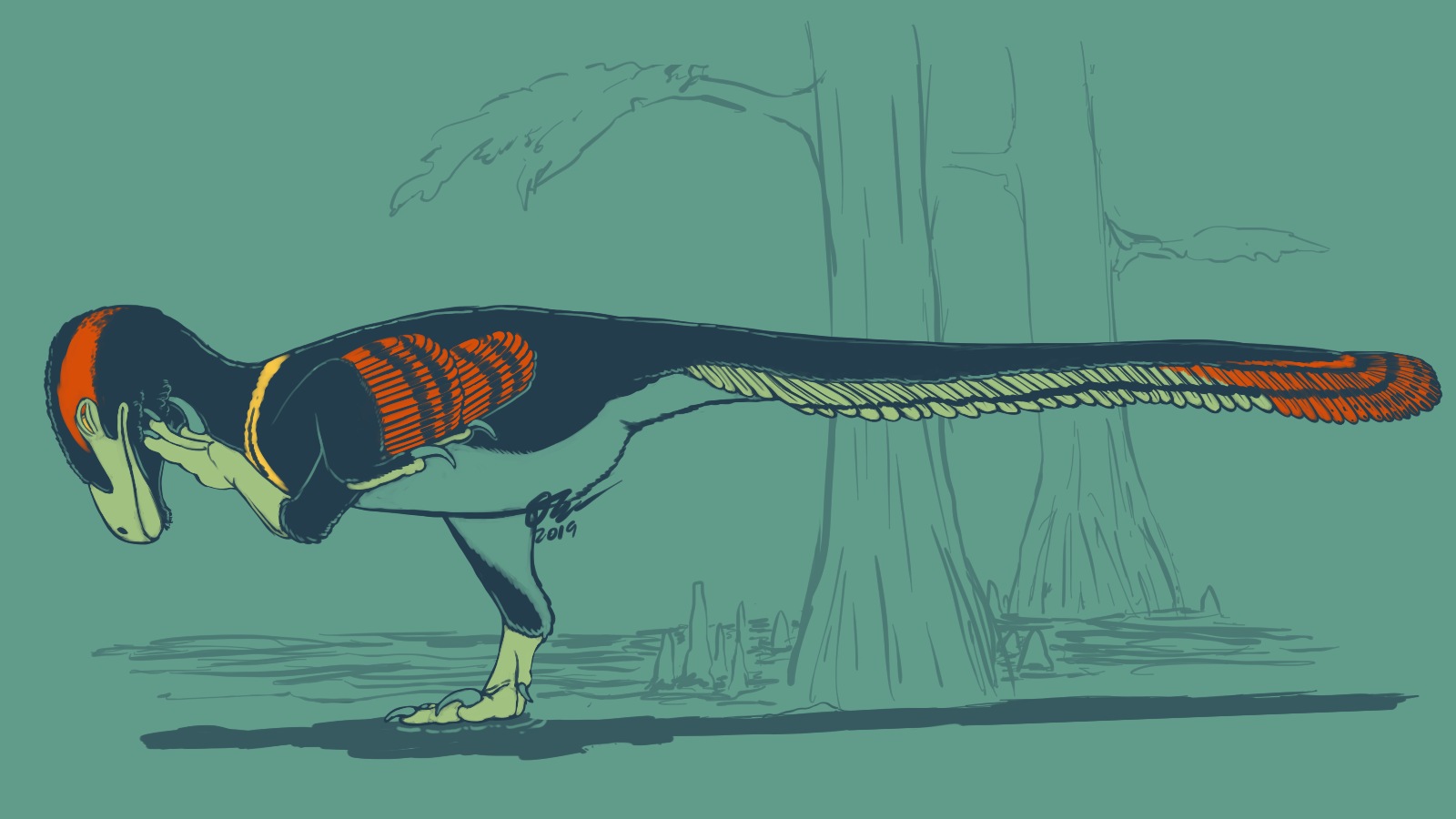

Yi, the genus discovered in 2015 that had evidence of wing membranes preserved, which upended our understanding of this group.

Eumaniraptora

Eumaniraptora (meaning “true hand thief”) is the final group of theropods we’ll examine here. It includes troodontids, dromaeosaurs, and birds. Famous members include Velociraptor, Utahraptor, Troodon, Deinonychus, and Microraptor. Troodontids and dromaeosaurs were famous for their hyperextended “killing claw” on each foot.

Dakotaraptor, one of the largest dromaeosaurs, lived in Latest Cretaceous Hell Creek, South Dakota alongside such fan favorites as Tyrannosaurus, Triceratops, and Pachycephalosaurus.

Ornithischia

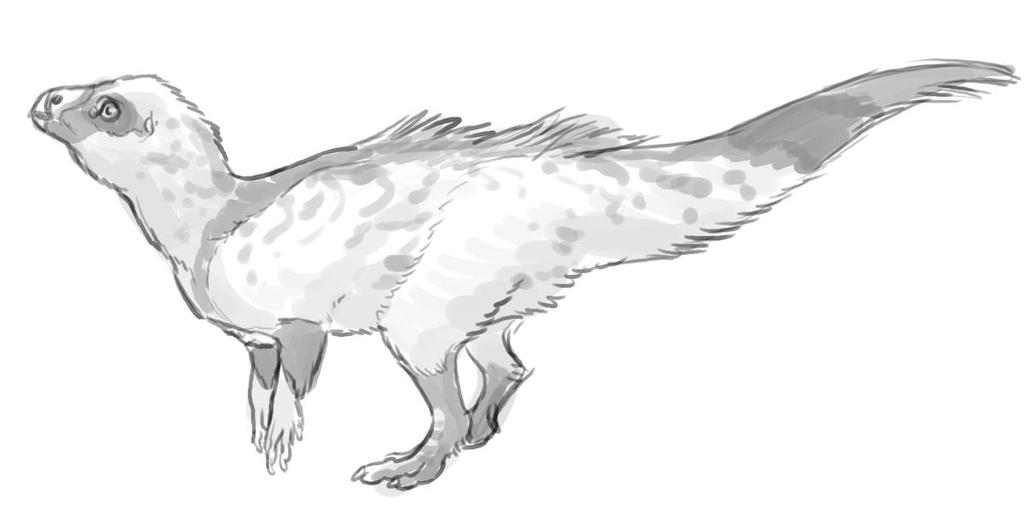

Ornithischians become recognizable a bit after saurischians did, in the Early Jurassic, and only became diverse in the Late Jurassic and onward. They started out small and unobtrusive, but grew to massive sizes by the end of the Cretaceous.

A fluffy reconstruction of Heterodontosaurus, a tiny basal ornithischian from the Early Jurassic that weighed only 4-8 pounds.

Scutellosaurus (meaning “little shield reptile”), a basal thyreophoran (relative of stegosaurs and ankylosaurs). This guy weighed around 20 pounds.

Thyreophora

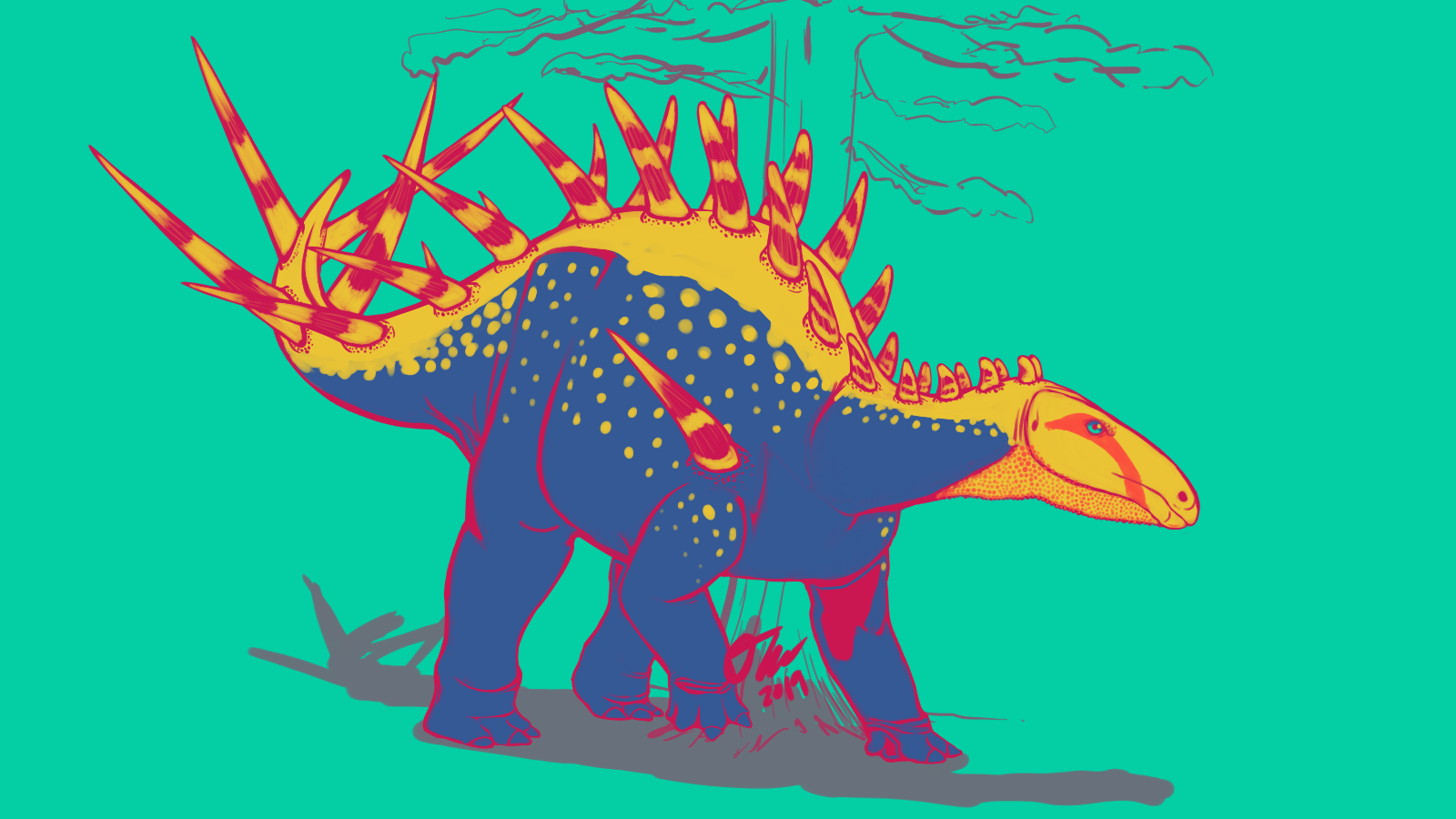

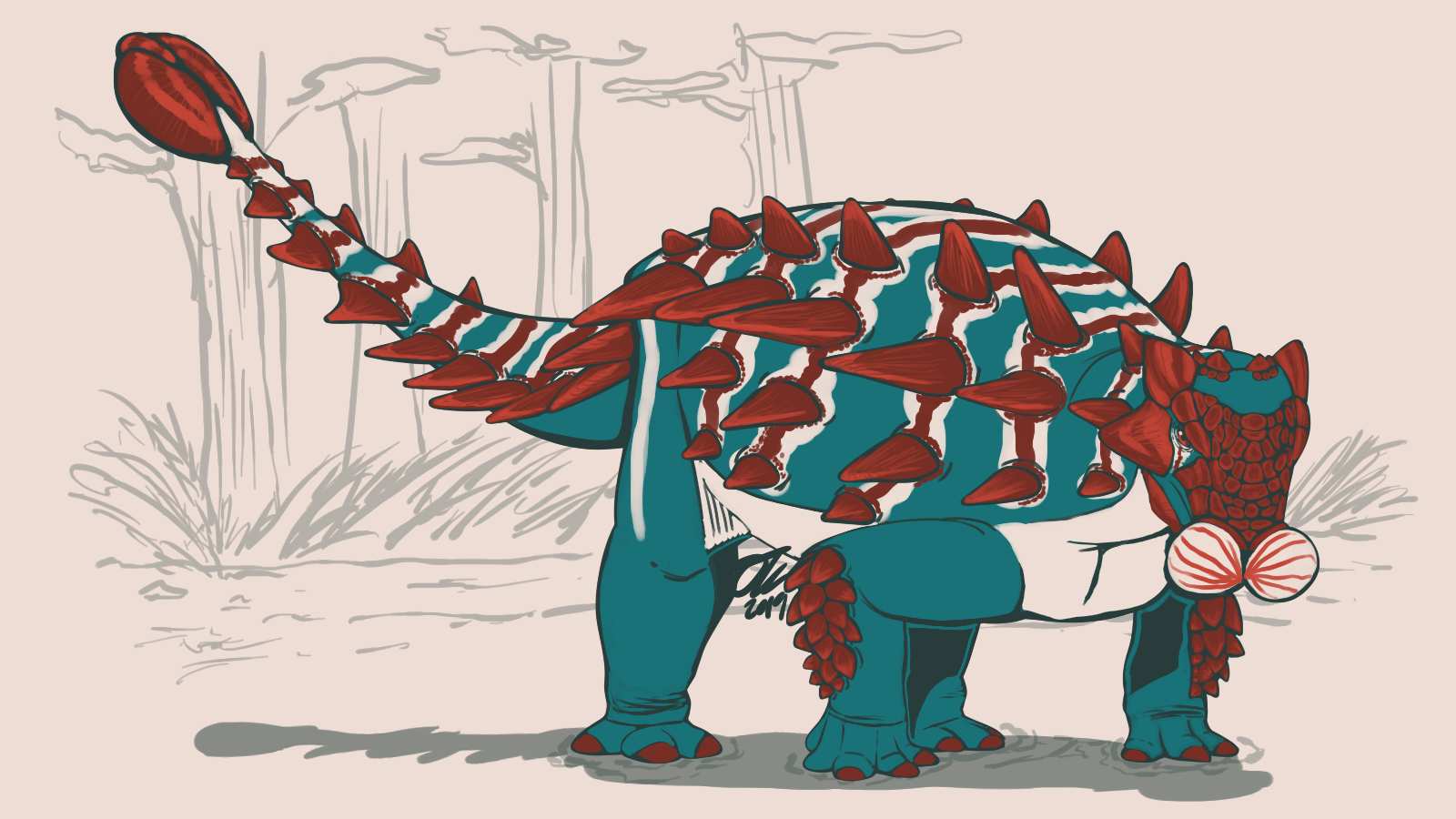

A group of very defense-oriented ornithischians, Thyreophora (meaning “shield bearer”) includes the plate-backed stegosaurs and the tank-like ankylosaurs. Stegosaurs had their heyday in the Late Jurassic, while ankylosaurs were at their most diverse in the Late Cretaceous, 100 million years later. Famous examples of stegosaurs include Stegosaurus, Gigantspinosaurus, and Dacentrurus. Famous exmaples of ankylosaurs include Ankylosaurus, Euoplocephalus, and Borealopelta.

Alcovasaurus, a rather spiky (as opposed to platey) stegosaur from Late Jurassic Wyoming. The spiky tail weapon is called a “thagomizer” and was named by Gary Larson in a Far Side cartoon.

Note: Imagine two stegosaurs mating. How do you think they’d accomplish that??

Zuul, an ankylosaur from Late Cretaceous Montana. Here it’s depicted with speculative soft nasal display structures. Zuul is named after the demon in Ghostbusters, whom it sort of resembles. Its species name, crurivastator, means “destroyer of shins.” Ankylosaurs may have dug for roots like pigs do today.

Note: Ankylosaurs almost always fossilize upside-down! This is because if the body ends up in water, all that armor on its back weighs it down and causes it to flip over. And sinking into the soft sediment in the water makes it more likely that the body will fossilize.

Ornithopoda

Ornithopods (meaning “bird foot”) were a group of herbivores from the Cretaceous that were skilled at chewing and often had extreme headgear. Various overlapping sugroups of Ornithopoda you may have heard of are the iguanodonts, the hadrosaurs, and the “duck-billed dinosaurs”. Some earlier or smaller ornithopods were bipedal, but the more derived members were quadrupedal. Famous members include Iguanodon, Parasaurolophus, Edmontosaurus, and Maiasaura. They were the cows of the Cretaceous, able to graze on whatever tough plants (including the first grasses) were around instead of browsing for particularly good plants.

Maiasaura, meaning “mother reptile,” was a Late Cretaceous ornithopod from Montana. The name refers to how the first fossils of Maiasaura were found among many nests with eggs and nestlings, indicating group-nesting behavior and parental care.

Note: Hadrosaurs in the past (especially Parasaurolophus for some reason) were often depicted with a bipedal, upright, kangaroo-like stance. We now know that they were usually quadrupedal, even though their front legs look super skinny.

Pachycephalosauria

Pachycephalosaurs (meaning “thick head reptile,” pronounced “PAK-ee-SEF-a-lo-sores”) were the famous dome-headed group of smallish bipedal herbivores from the Late Cretaceous. Famous members include Pachycephalosaurus, Stegoceras, and Homalocephale (Stygimoloch and Dracorex are also often cited as their own groups, but recently they were found to be juvenile forms of Pachycephalosaurus). Pachycephalosaurus itself lived in Latest Cretaceous Hell Creek alongside Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops. There’s evidence of wounds in many pachycephalosaurid domes that indicate they did indeed head-butt each other.

Saurian’s reconstruction of a Pachycephalosaurus.

Ceratopsia

We’ve reached the end! Ceratopsians (meaning “horned face”) are the last group of dinosaurs we’ll examine, and they’re one of the most famous and charismatic. They were herbivorous, and had a small to extremely large bony frill that covered their necks. The smaller and earlier ones were bipedal and had porcupine-like quills on their tails, while the larger and later ones were quadrupedal and had extensive frill ornamentation. Famous examples include Triceratops, Protoceratops, and Psittacosaurus.

Machairoceratops, from Late Cretaceous Utah.

Psittacosaurus, a basal ceratopsian from Early Cretaceous Asia, with a minimal frill and prominent tail quills. Note: Many (up to twelve) different species of Psittacosaurus are known, and not all species had tail quills.

Thanks for bearing with me through all these groups! I hope you feel like you have a better understanding of the main groups of dinosaurs and how they relate to one another.

Image credits: Hip Comparison Buriolestes Coelophysis Plateosaurus Air Sacs Bird Lung Diplodocus Amargasaurus Giraffatitan Argentinosaurus Carnotaurus Spinosaurus Giganotosaurus Tyrannosaurus Ontogeny Struthiomimus Therizinosaurus Oviraptor Yi Dakotaraptor Heterodontosaurus Scutellosaurus Alcovasaurus Zuul Maiasaura Pachycephalosaurus Machairoceratops Psittacosaurus