Family tree: Ornithischia > Neornithischia > Cerapoda > Marginocephalia > Ceratopsia > Psittacosauridae

Hometown: Eastern Asia, 126-101 million years ago (Early Cretaceous)

Discovered 1922 and described 1923 by Henry Fairfield Osborn

Psittacosaurus, meaning “parrot reptile,” was a goat-sized basal ceratopsian (early relative of the later horned faced dinosaurs, including Triceratops) that is probably the one non-avian dinosaur best understood by science. It’s known from hundreds of specimens that represent at least 12 species, and range in age from hatchling to elderly individuals. Also, having been described almost a century ago, scientists have had plenty of time to subject various specimens to all kinds of tests. Because of all this, we know a ton about this little dinosaur’s life appearance, the way it grew and developed, and how it behaved.

Life Appearance

Psittacosaurus was a small, scaly, bipedal dinosaur with an unusually short, beaked snout (from which it gets its name). In addition to the beak in the front of its mouth, it had teeth further back, and, like nearly all ornithischians, was an herbivore. While Psittacosaurus didn’t have the bony frill characteristic of later ceratopsians, it did have various facial horns and bosses that differed between species. All species possessed long jugal (cheek) bones that were probably covered in keratin (horn/fingernail material) in life.

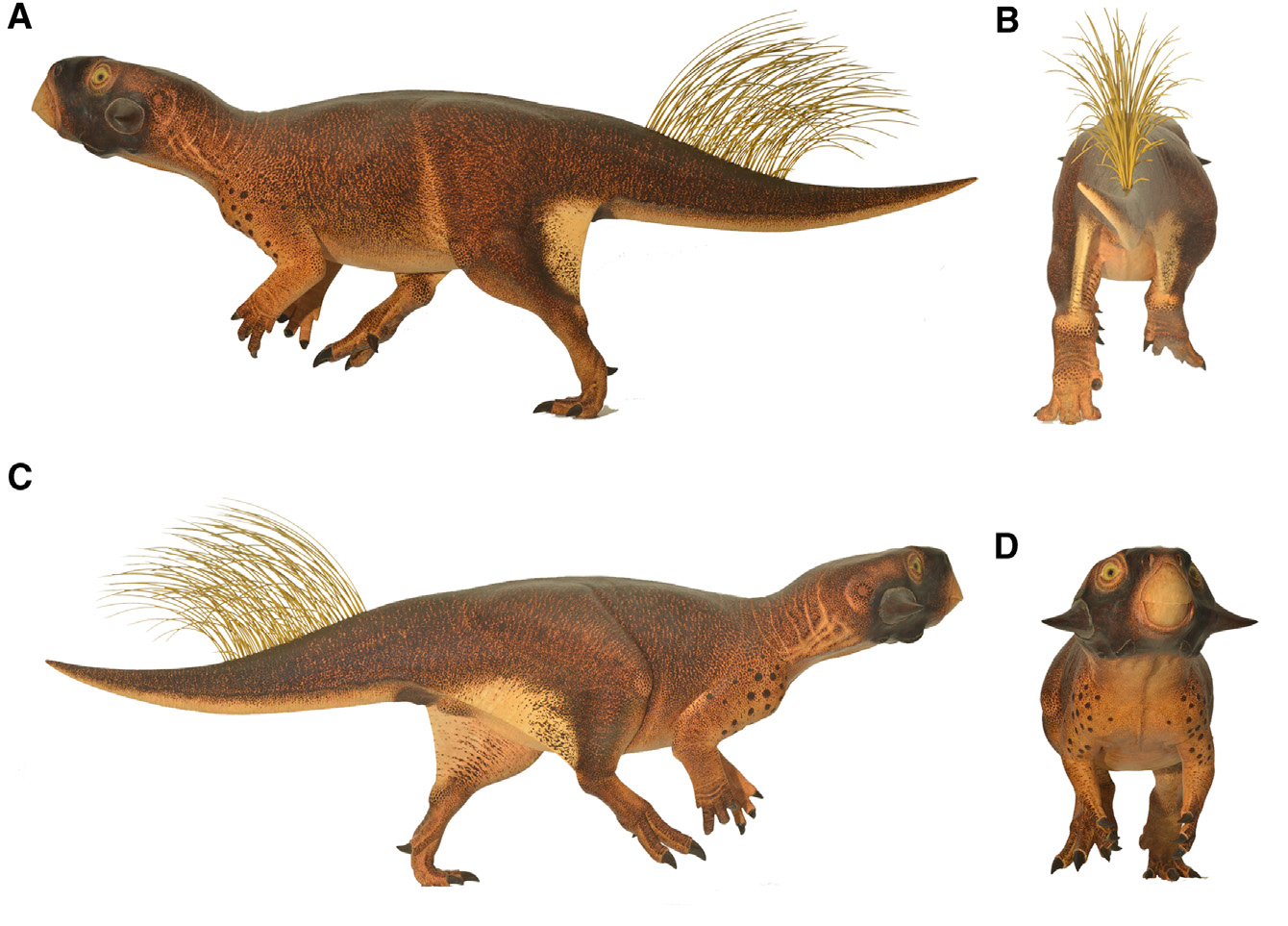

Psittacosaurus is one of the few scaly dinosaurs whose color we know in its entirety. Using melanosome analysis, Jakob Vinther (the guy who invented melanosome analysis) and his team mapped the color of the animal’s entire body, producing this reconstruction:

Isn’t it cute? It had a black face, a dark back and vent, and a light underside. Its back and legs sported a disruptive brindle-like pattern that would’ve helped it to camouflage. In the same study, the authors also concluded that Psittacosaurus’s specific type of faded countershading would have been optimal for camouflaging in a shady, forested environment [1].

In addition to its color, we know a lot about Psittacosaurus’s skin, both inside and outside. How the skin was structured is outside the scope of this post, but if you’re interested you can read more about it (and look at pretty pictures of fossils) in the original paper [2]. On the outside, Psittacosaurus had large scales spaced widely apart, with the intermediate area filled by smaller scales, a pattern also found on other ceratopsians. It also had larger, dark-colored osteoderms on its shoulders, as you can see in the above reconstruction. On the back of its legs, it had large patagia, or skin flaps, connecting the ankle to the tail. It also had a callused sit pad on its bum. I love that we know that.

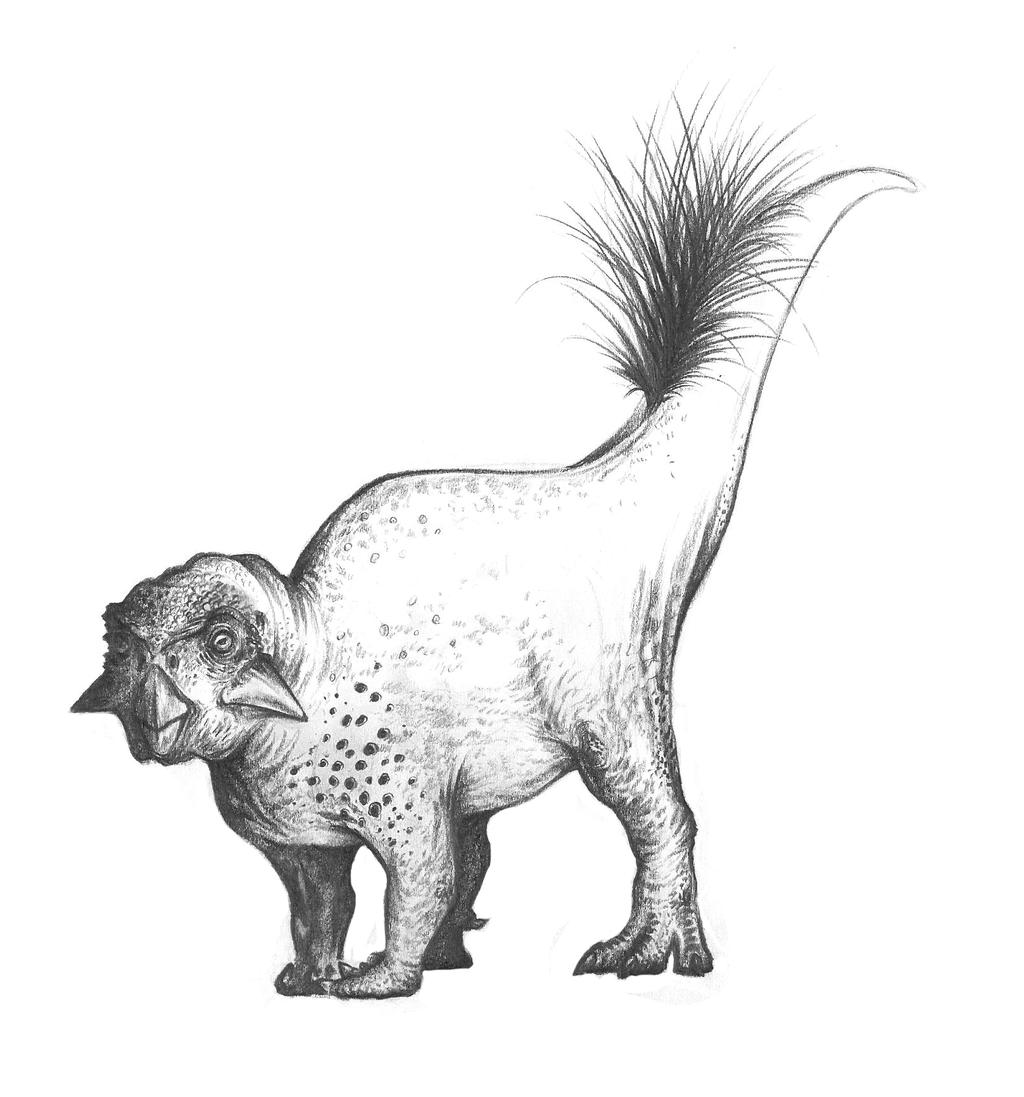

And now for the elephant in the room–the tail bristles! These are only known from a single specimen–the same specimen examined for color mentioned above–so it’s unknown whether all species of Psittacosaurus had them or just one, or even if it was a sexually dimorphic trait. However, multiple rigorous studies on these bristles confirmed that they are truly bristles belonging to the animal and not some plant material it died on, or some other trick of taphonomy [3]. It’s still inconclusive whether they are actual protofeathers or if they’re a different structure, but it’s generally agreed that they are at least homologous to feathers [4]. Once these were described, paleoartists began giving porcupine-like tail quills to all kinds of ceratopsians and pachycephalosaurs:

I love speculative paleoart, but I’m not sure I believe that quills were that widespread among dinosaurs for a couple reasons. First, most animals today aren’t quilly, and there’s no reason to believe the Mesozoic was different. And second, quills preserve better than soft structures like skin and feathers because they’re harder, leading to probable overrepresentation of this type of integument in the fossil record relative to others. But then again, there’s not really strong evidence against Styracosaurus possessing quills, so why not?

Note that all of the above life appearance info really only applies to one species of Psittacosaurus. As we know from modern animals, different species in the same genus can look vastly different–take, for example, Panthera leo (lion), Panthera pardus (leopard), and Panthera tigris (tiger). They’re completely different in terms of appearance, size, behavior, and habitat, even though they’re all very closely related, within the same genus. It’s possible that other species of Psittacosaurus looked much different than the reconstruction above.

Ontogeny

In addition to its life appearance, we know a lot about how Psittacosaurus grew and developed. Rigorous and granular growth curves have been constructed, allowing scientists to estimate an individual’s age from the length of its femur (thighbone), which is especially helpful when cutting a bone open to inspect its histology isn’t an option. Psittacosaurus grew more quickly than modern non-avian reptiles and marsupials, but more slowly than modern placental mammals and birds, a finding consistent with growth studies on other types of dinosaurs [5].

One somewhat unusual habit of Psittacosaurus is that it seems to have been quadrupedal as a hatchling, but switched to bipedality sometime in its second or third year of life. This conclusion is based on the way the ratio between the length of the animal’s arms and legs changed as it grew: as a baby, Psittacosaurus’s arms and legs were almost the same length, but as an adult, the arms were just 60% of the leg length [6]. It’s generally accepted that adult Psittacosaurus were obligate bipeds, since they share numerous skeletal similarities with other known bipedal dinosaurs and since their arms didn’t have the range of motion necessary to even reach the ground while standing. Like many dinosaurs, adult Psittacosaurus also didn’t have ability to twist their forearms so that their palms were pronated (facing the ground), and as far as we can tell they didn’t exhibit any adaptations for knuckle-walking or sideways-fingered, karate-chop locomotion, so it’s unclear how exactly the putatively quadrupedal juveniles would’ve walked [7].

Above: A Psittacosaurus juvenile, speculatively walking on the backs of its hands. Seems uncomfortable to me, but what other type of quadrupedal locomotion hasn’t been ruled out? It’s also possible that the juveniles’ arm bones differed in some key way from those of adults, but that also seems unlikely.

This transition from quadrupedal to bipedal isn’t unique to Psittacosaurus; certain basal sauropods like Massospondylus and Mussaurus, as well as the basal ornithopod Dryosaurus, also show evidence of this strategy. Certain other dinosaurs did it the opposite way, going from bipedal juveniles to quadrupedal adults, including the ornithopods Maiasaura and Iguanodon, and an unknown apatosaurine (below).

Above: Numerous weird little bipedal sauropods run clumsily from a subadult Allosaurus who is taking advantage of the surplus seasonal food source. Evidence for bipedality in these long-necked dinosaurs comes from a trackway in Colorado [8].

Lifestyle

There’s a lot to unpack about what we know about Psittacosaurus’s lifestyle, so I’ll start with the very basics: what did it eat? Funnily enough, we don’t actually know. It was clearly an herbivore, and its beak would’ve been good for either cropping vegetation or for cracking nuts. Some specimens have gastroliths preserved in their guts–these are small rocks ingested on purpose to aid with mechanical breakdown of food, a strategy used by many modern groups including birds, crocodiles, whales, and seals. These have so far only been found in adult specimens, indicating that maybe adults preferred tough, fibrous nuts while juveniles ate soft plants.

Even though we don’t have direct evidence for what it ate, we do have direct evidence for what ate it! The wolverine-sized mammal, Repenomamus, is known from a fossil preserving stomach contents to have eaten a hatchling Psittacosaurus.

In addition to this direct evidence, we can assume that even adult Psittacosaurus would’ve been targets for larger predators in its ecosystem, including large dromaeosaurs like Zhenyuanlong, the small tyrannosauroid Dilong, the giant compsognathid Sinocalliopteryx, and the apex predator of Yixian, the fluffy giant Yutyrannus. For more info on the Yixian ecosystem and its inhabitants, see my Paleo Biome Profile!

Another interesting behavior particular to Psittacosaurus is that juveniles tended to form little herds from six to 34 individuals. This makes sense as a defensive strategy, since as we’ve seen, hatchling Psittacosaurus were vulnerable to predation. However, strangely, none of these herds had any adult supervision, and often the younguns in the herds were of varying ages, meaning they came from different clutches, if not different parents, and formed these groups because they wanted to, rather than because they were in the same nest at the same time [10].

Above: A herd of Psittacosaurus of varying ages runs from an offscreen danger. Here, they are interpreted as being facultatively bipedal–that is, they would’ve been quadrupedal when walking or standing, but bipedal when running. The younger individuals are also stripier, a common strategy among modern herbivores.

The fossil of 34 juveniles I mentioned above was originally thought to have been associated with the skull of an adult, presumed to be a parent. However, it was later realized that the adult’s skull was just glued on, and anyway it wasn’t old enough to bear children (Psittacosaurus didn’t reach sexual maturity until it was 10 years old, and the skull belonged to a 6-year-old subadult) [11].

Conclusion

This has definitely been the most detailed and extensively-researched Obscure Dinosaur Profile I’ve done so far. There’s a lot to say about this little ornithischian! I think it’s pretty incredible both how much material the fossil record preserves, and also how much we can learn from studying fossils in different clever ways. In some cases, paleontologists understand more about how ancient animals tick than how modern animals do, and the need to compare with modern analogues is what prompts the in-depth study of living animals. I hope this dive into the nitty-gritty of Psittacosaurus has helped to flesh out at least this one dinosaur as a real, living animal with all its idiosyncrasies and complexity. Too often, only one or two aspects of a dinosaur’s lifestyle are really explored or depicted: running and eating. But as with all animals, there’s a lot more to living than that!