I was already planning on doing a post on ghost lineages when fortuitously, it came up as a prompt in Spectember. So to start, I’ll just quote myself here:

A ghost lineage is when a certain species or group disappears from the fossil record for a time, then reappears later. They continued living during the gap, as evidenced by their surviving descendants, but we don't know at all what they were doing during that time.

This post will essentially just be a list of a few particularly interesting or egregious cases of ghost lineages in the fossil record. For a more detailed explanation of what a ghost lineage is, check out this short article. I won’t mention the archetypal example, coelacanths, in this post, because of how well that article describes them.

Jakapil

Family tree: Dinosauria > Ornithischia > Thyreophora (?)

Hometown: Argentina, early Late Cretaceous (97-94 million years ago)

Discovered 2012, described 2022

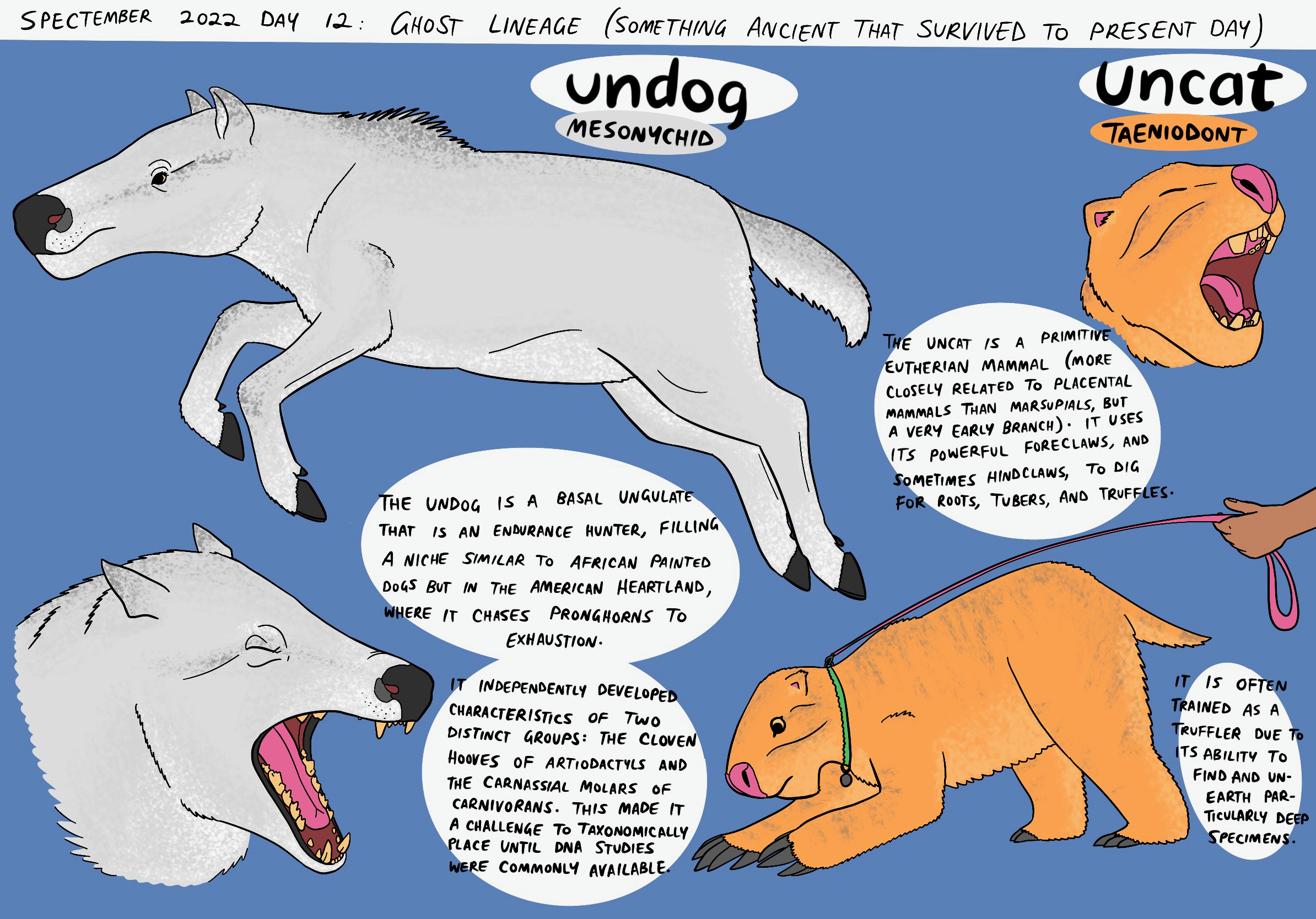

The main inspiration for this topic was the recent publication of the new bipedal, armored Cretaceous dinosaur, Jakapil.

Herbivorous dinosaurs mostly came from two groups: Thyreophora, the armored dinosaurs, including Stegosaurus and Ankylosaurus; and Neornithischia, which includes the “duck-billed” dinosaurs like Parasaurolophus, horn-faced dinosaurs like Triceratops, and head-butting dinosaurs like Pachycephalosaurus, among others. Primitive thyreophorans were small and bipedal, but had the beginnings of armor, and were thought to have died out in the Early Jurassic, around 181 million years ago, making way for the diversification of the more derived stegosaurs and ankylosaurs. However, only three genera of non-stegosaurian, non-ankylosaurian basal thyreophorans were known: Scutellosaurus (below), Scelidosaurus (two below), and Emausaurus, which is only known from fossil fragments.

The new naming of the much younger Jakapil increases the known diversity of basal thyreophorans by a third and creates an 84 million year ghost lineage. That is, assuming it is truly a basal thyreophoran. Jakapil has several characteristics in common with other thyreophorans, especially Scelidosaurus, including skull, rib, and limb features, as well as telltale osteoderms (bony armor growing in the skin). However, it also shares features with heterodontosaurs (a very primitive branch of herbivorous dinosaurs) and ceratopsians (horn-faced dinosaurs), such as a predentary bone (an extra bone at the tip of the jaw) that supported a beak, and a chewing style better suited for mashing tough vegetation than selectively browsing. However, it’s definitely possible that those features are convergent, if Jakapil evolved them in response to shifting its diet toward tougher foods.

The other interesting thing about Jakapil is its beefy lower jaw. It definitely had an unusually strong bite and advanced chewing ability for a thyreophoran, but osteological correlates on the lower jaw and the presence of a separate potential muscle attachment point indicate that the large crest might not have been for anchoring jaw muscles, but rather for visual display.

This study also corroborates previous discoveries of isolated osteoderms from Early Cretaceous Argentina, which hadn’t been able to be assigned to any potential owner. They weren’t from the same time period as Jakapil, but now that we know that its ancestors must have been living there during the ghost gap, we at least have some idea of what those creatures may have looked like.

It’s super cool to be able to place an entirely new type of animal into our picture of a certain paleoenvironment, but I don’t think it should be a surprise that we can still discover things like this. A vast majority of species never fossilize, so it’s likely that we’ve never found the many creatures that were either rare in their habitats or lived in places not conducive to fossilization. Imagine future paleontologists unearthing something like a kinkajou when they already knew of various types of cats and dogs. Its combination of basal and advanced features might throw them for a loop!

Chilesaurus

Family tree: Dinosauria > ???

Hometown: Chile, Late Jurassic (145 million years ago)

Discovered 2004, described 2015, reclassified 2017

I’ve already done an entire profile on Chilesaurus, so I won’t go into much detail here other than to mention that if it’s really a basal ornithischian, that would imply a ghost lineage of also around 84 million years. Huh, same number–weird coincidence.

You can read more about the structure of the dinosaur family tree in my post from 2019!

Chronoperates

Family tree: Mammalia > Holotheria > Symmetrodonta (?)

Hometown: Canada, Late Paleocene (55 million years ago)

Discovered and described 1992, reclassified 1997

Now we move to the land of mammals, one of the reasons that this post isn’t an Obscure Dinosaur Profile. I’ve described the early and recent mammal family tree in previous posts, so go there first if you want some context (and have some time).

Chronoperates means “time wanderer”, because this animal, known only from a partial jawbone (like most ancient mammals), was initially thought to be an extremely late-surviving non-mammalian cynodont, implying a ghost lineage of over 100 million years. However, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and the fossil was soon scrutinized and the non-mammal identity cast into doubt. It was reidentified as a symmetrodont, a group of mammals more closely related to marsupials and placentals than to monotremes (egg-laying mammals), although it’s unclear whether Symmetrodonta is a legitimate clade or a wastebasket taxon. This decreases the ghost lineage to a much more reasonable 17 million years–barely long enough to really be considered a ghost lineage! However, it’s an important stretch of time since it overlaps the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary, letting us known that symmetrodonts did survive the asteroid impact in some capacity.

The above picture of Chronoperates is extremely speculative, given how little is known about its anatomy. It’s reconstructed by making inferences based on its symmetrodont relatives, mostly the similar and much better-known Zhangheotherium. The venomous foot spurs that now only male platypuses have were probably an ancestral trait to all mammals; Zhangheotherium had them, so Chronoperates here does too.

Necrolestes

Family tree: Mammalia > Cladotheria > Dryolestida (?)

Hometown: Argentina, early Miocene (21-17.5 million years ago)

Discovered and described 1891, reclassified 2012

A neighboring clade to the symmetrodonts, Necrolestes is thought to be a member of the dryolestids, a group known mostly from the Late Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous. While the Chronoperates reclassification narrowed its ghost lineage length, this one did the opposite. Necrolestes was for over a century thought to be a therian (placental or marsupial) mammal of some stripe, both of which were very common in South America at the time. However, it was finally reexamined in 2012 and placed outside Theria, which resulted in a ghost lineage of 40 million years.

While known from better fossil material than Chronoperates, Necrolestes’s anatomy is not super well understood. We have fragments from four different individuals, making up about a third of the skeleton and most of the skull, and can tell that it must have been doing something rather unusual, but aren’t sure exactly what. As you can see in the picture above, the tip of its upper jaw curved dramatically upward, interpreted as supporting a fleshy, sensitive nose tip, perhaps for sensing prey in burrows like a mole. However, even star-nosed moles and pigs, which have such fleshy, touch-sensitive nose organs, do not show skull adaptations like this. So it’s still unclear how Necrolestes really lived.

By the way, have you ever seen a (regular, laurasiatherian) mole move outside of its burrow? It army crawls with its hands up near its face as if it’s still underground!

Lazarussuchus

Family tree: Reptilia > Diapsida > Choristodera

Hometown: Europe, Paleocene to Miocene (61-12 million years ago)

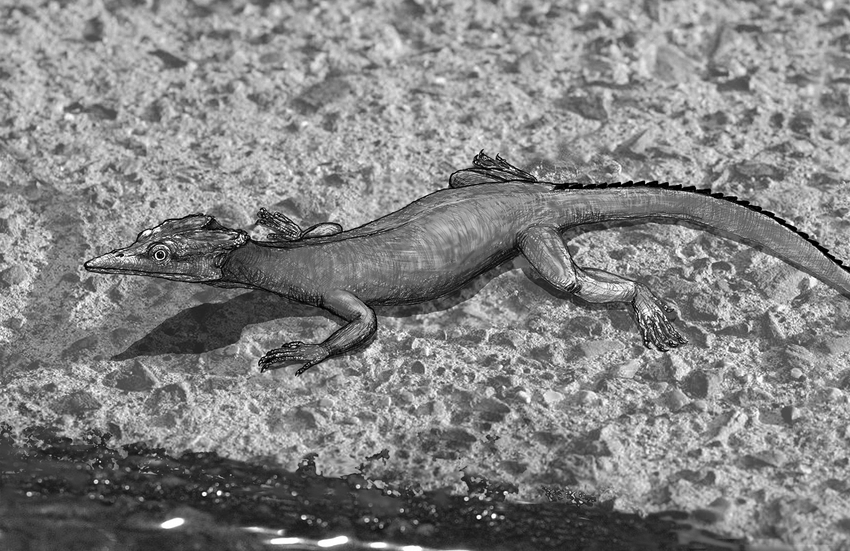

Last but certainly not least, we’ll look at the only non-dinosaur reptile in this post, Lazarussuchus, whose name comes from the fact that it’s a “Lazarus taxon”, or the descendant of a ghost lineage.

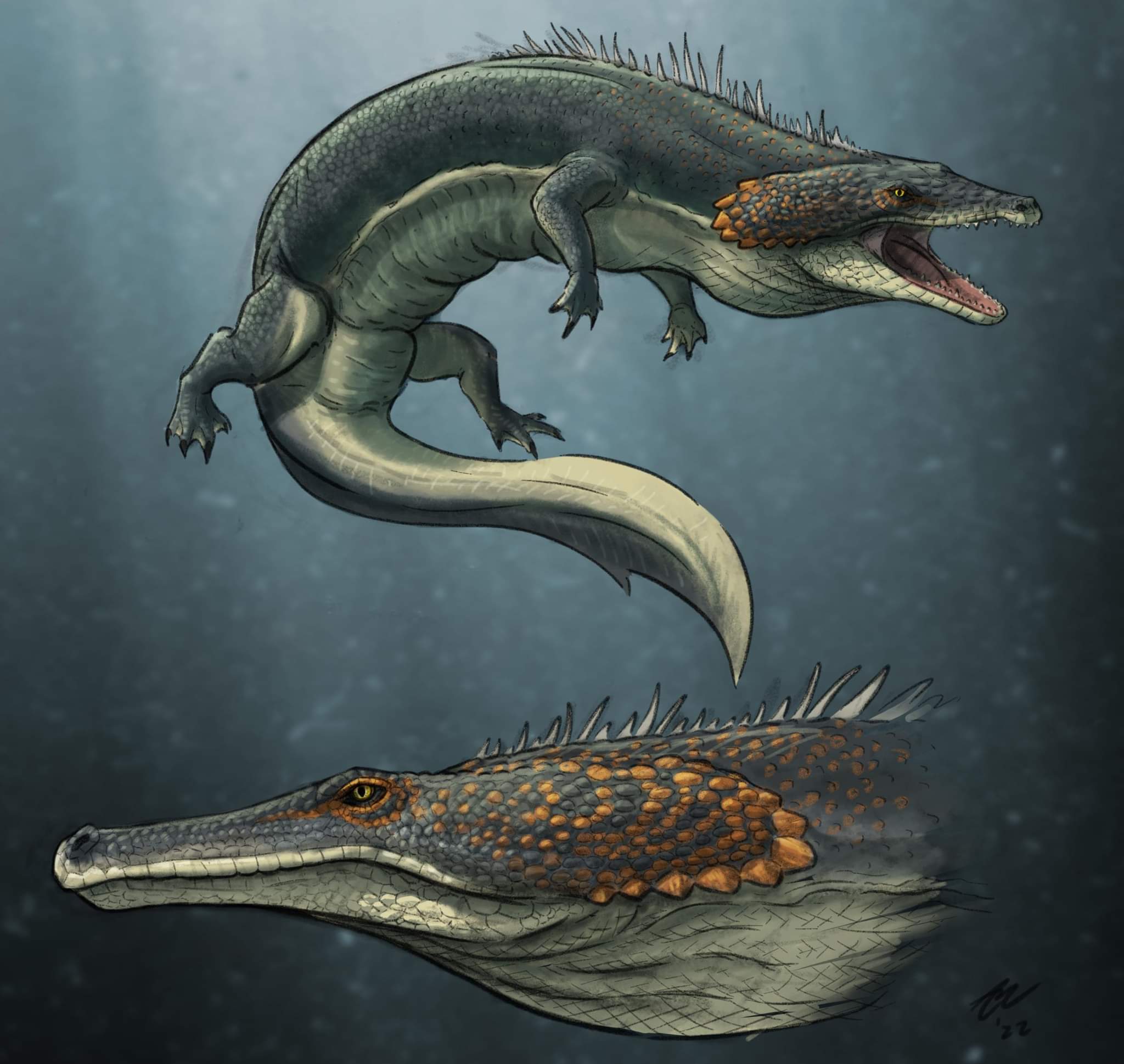

Choristoderes were a group of mostly aquatic or semiaquatic reptiles that were important parts of ecosystems throughout the Mesozoic. Many of them were large, long-snouted piscivores that looked a lot like unarmored gharials, and indeed gharials didn’t diversify until the large-bodied choristoderes went extinct.

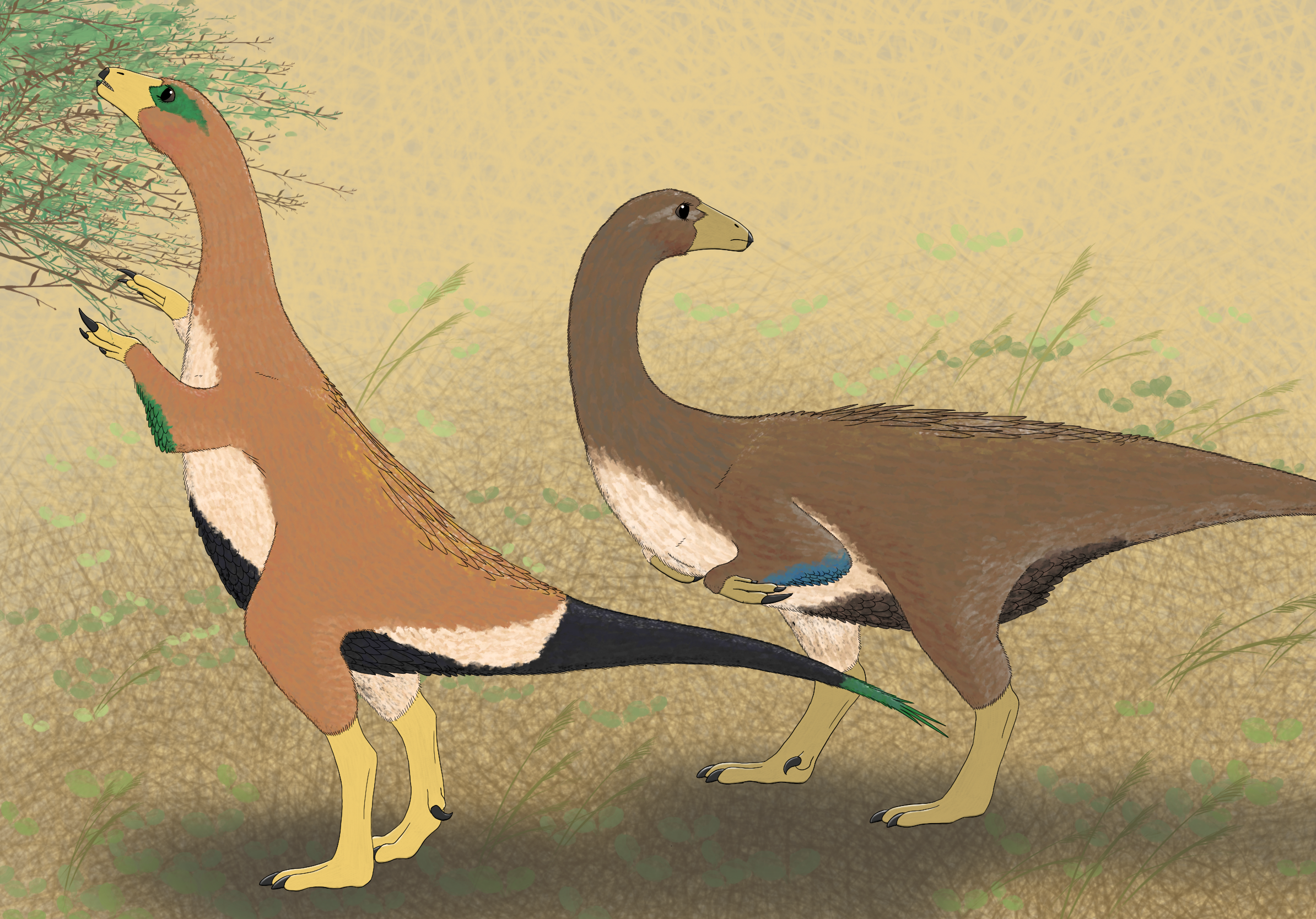

Above: The newly-described Kosmodraco, a large choristodere with interesting ornamental skull flanges.

Other choristoderes were tiny, like the foot-long Monjurosuchus and little long-necked Hyphalosaurus from Early Cretaceous China (for pictures, ctrl-F their names in my Yixian biota post). Many choristoderes were fully aquatic, with the males incapable of moving on land, but with the females able to haul out to lay eggs or give live birth (a trick that would be highly unusual among archosauromorphs, if that’s what they are). However, some trackways (fossil footprints) attributed to choristoderes show that some of them were capable of high-walking on land like crocodiles, holding their bellies off of the ground.

While the subgroup known as neochoristoderes, which were mostly large-bodied, croc-like ambush predators, persisted into the Eocene (56 million years ago), the “allochoristoderes” (a paraphyletic group of all non-neochoristoderes) appeared to have died out by the end of the Early Cretaceous, around 100 million years ago. But then in 1992, Lazarussuchus was described from the Oligocene of France, at a mere 28 million years old. Not only was it much younger than other “allochoristoderes”, but it seemed to be more primitive than the Cretaceous forms, most closely resembling the very basal Jurassic choristodere Cteniogenys, which lived somewhere between 168 and 150 million years ago. This would imply a ghost lineage of at least 122 million years.

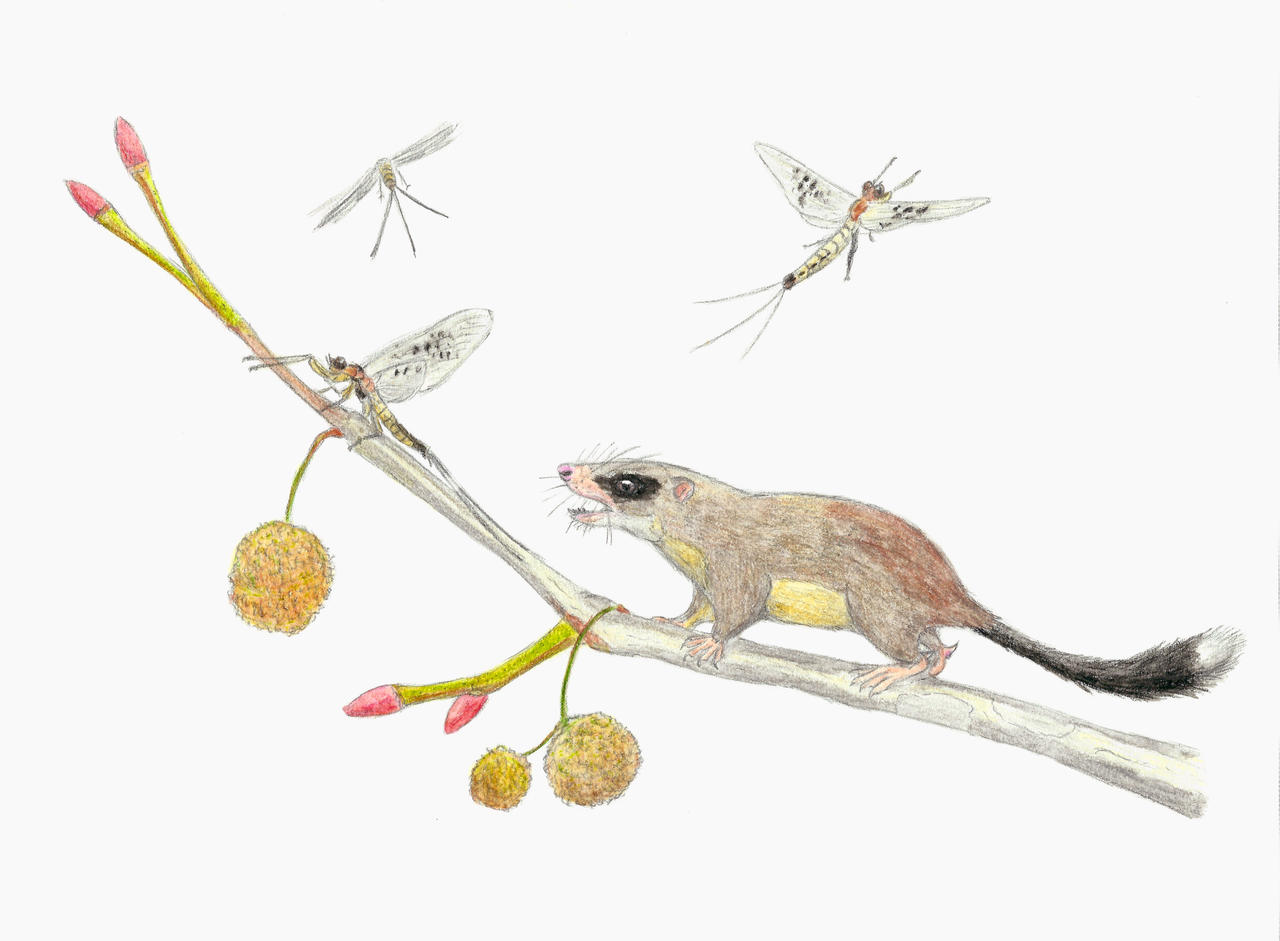

Above: Lazarussuchus was a foot-long, superficially lizard-like choristodere that was probably an insectivore.

Things got even spicier with the description of a second species of Lazarussuchus in 2005 that was even younger, at a mere 12 million years of age, making it by far the latest-surviving choristodere. However, an exquisitely-preserved fossil from the Paleocene of France, 61 million years old, described in 2012, shortened the gap to 89 million years, still the longest ghost lineage we’ve looked at so far.

In addition to the gap between Cteniogenys and Lazarussuchus, though, there’s also a gap between the inferred first appearance of choristoderes in the earliest Triassic at the latest and the Middle Jurassic Cteniogenys, which is the oldest unambiguous fossil choristodere. These kinds of gaps are very common in the fossil record, but this one is still notably long, at–you guessed it–84 million years. It’s the ghost lineage magic number, apparently.

For context, 84 million years ago our ancestors would have looked like a tiny shrew, and true placental mammals hadn’t even evolved yet. That is a very long time for a lineage to lie in wait!

Above: Yes, our ancestor is the one getting attacked by the Velociraptor. How humiliating.

Image credits and sources

Jakapil 1 Scutellosaurus Jakapil 2 Jakapil paper Chronoperates blog post Chronoperates Necrolestes Kosmodraco Lazarussuchus Choristodere ghost lineage Zalambdalestes