I’ve discussed how physics doesn’t act the same at different size scales before, so if you haven’t read that post yet, please check it out first! In this post, I’m going to cover some additional examples of how the very smallest beings go about their lives, and what kinds of adaptations they need to cope with strange lilliputian physics.

Small vertebrates’ sense of balance

There have been two recent studies discussing the effect of Reynolds number (equal to density times flow speed times scale length divided by viscosity–a detailed explanation can be found in the post linked above) on animals’ sense of balance: one about the world’s tiniest living frogs, known adorably as pumpkin toadlets, and one about ancient mammal relatives.

In your inner ear, you have structures known as semicircular canals: three fluid-filled tubes arranged at right angles to one another, lined on the insides with tiny hairs. When you move your head, the fluid inside sloshes, moving the hairs, which transmit signals to your brain telling you exactly how you’ve just accelerated.

When you scale down the size of these structures, though, the fluid acts differently: the Reynolds number decreases linearly with scale length, meaning that the same fluid (endolymph, similar in properties to water) flows more viscously when the canals are smaller. When the fluid inside is more viscous, the time delay between movement and bending the tiny hairs increases, slowing the animal’s reaction time. In the tiniest vertebrates, pumpkin toadlets, the semicircular canals are as big as they can possibly be while still fitting inside the frog’s minute skull, but even so this isn’t really big enough for a good sense of balance. As a result, the toadlets can jump–but they can’t land.

As soon as the little frog takes off, its endolymph can’t flow fast enough to allow it to know what orientation it’s at in the air. It just turns into a weird stiff doll and crash-lands ungracefully. Luckily, it’s so small that the landing doesn’t hurt it (because the strength of bones and muscles is proportional to cross section while mass is proportional to volume, due to the square-cube law). However, because of this loss of control, they only tend to hop when threatened, rather than for getting around. Instead, they walk awkwardly, their legs moving like stiff toothpicks (their sense of balance isn’t great even when not in the air). [1]

There are additional hilarious gifs in the news article.

What’s the advantage of being so small that you can’t even land your own jumps? There are many advantages to miniaturization, the main ones being (a) needing less resources, (b) being better able to camouflage and hide in crevices to avoid predation, and (c) potentially being able to utilize resources that a larger animal wouldn’t be able to access (more on this in the next section). Pumpkin toadlets live among leaf litter on the forest floor and rarely move, relying on either aposematic (warning) coloration or camouflage to keep from being eaten, and conserving energy by staying still, sometimes for literally years. Since they hardly ever hop, and when they do, they land among other leaf litter and would then be extremely hard to find, sticking landings is low on their list of priorities.

Another interesting new study about semicircular canals has to do with how their size correlates with body temperature. Since viscosity goes down when temperature goes up (think of how microwaving honey makes it more pourable) and vice versa, colder-bodied animals have to have proportionally larger semicircular canals, increasing the scale length in order to compensate for the increased viscosity to keep the Reynolds number the same. And warm-blooded creatures don’t want their semicircular canals to get too big, or the endolymph will slosh around unpredictably and may not push the hairs in the same direction as the acceleration. Thus, it’s not the largest animals (whales) that have the largest semicircular canals–whales’ are only slightly larger than humans’–but the largest cold-blooded animals, the whale sharks.

We can use this correlation to estimate the body temperatures of extinct creatures. Using a model based on 277 living species of mammal and reptile whose body temperatures are known, the researchers in the recent study examined 64 extinct species of synapsid (mammal relative). There appeared to be an abrupt shift about 233 million years ago in the Late Triassic between the large, spacious type of semicircular canal expected for cold-blooded animals and the small, narrow canals of warm-blooded animals, indicating that endothermy evolved at that time. [2]

However, scientists have other avenues to estimate the body temperature of an extinct animal, and these point to a much earlier origination of endothermy. The main ones are bone histology, or looking at the “tree rings” and other patterns present in thin cross-sections of bone under a microscope, which I’ve discussed in detail in a previous post; predator-prey ratios (previous post); the presence of fossilized fur in a Permian coprolite (previous post) [3]; and oxygen isotope ratios, which correlate with average body temperature [4]. These lines of inquiry estimate a Late Permian start for endothermy, somewhere around 253 million years ago, arising independently among two different synapsid groups, the dicynodonts and the cynodonts. The 20-million year discrepancy between the two estimates makes me suspicious of the semicircular canal study, but unfortunately it’s paywalled, so I haven’t been able to read it in its entirety. Even if the transition between the different types of semicircular canal doesn’t line up perfectly with the advent of endothermy, the correlation could still hold over longer time periods, and it will be interesting to see more research along these lines investigating other groups, such as archosauromorphs (ancient croc and bird relatives) and marine reptiles.

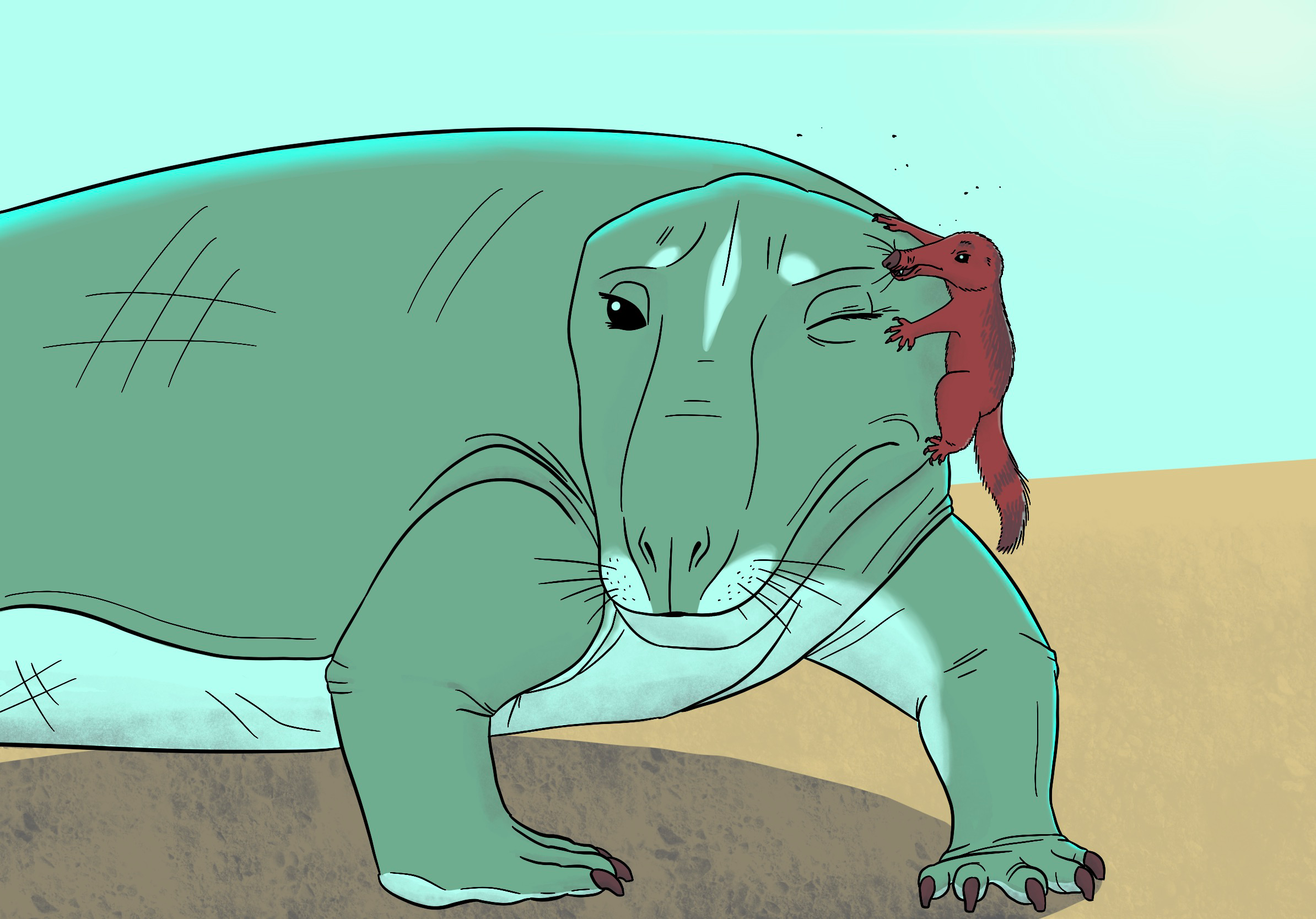

The page image up top is of two early Late Triassic synapsids, the large, herbivorous non-mammaliamorph cynodont Exaeretodon and the small mammaliamorph Pseudotherium, both from the Santa Maria formation in Brazil. If the semicircular canal study is correct and endothermy arose suddenly at this time and only among mammaliamorphs, then these two closely-related animals would have looked very different from each other: the ectothermic non-mammaliamorph Exaeretodon here has bare skin, while the endothermic Pseudotherium has thick fur. I still tried to make Exaeretodon a little reminiscent of mammals in its whiskers and eyelashes (which the first hair was probably used for before it was repurposed for insulation) and in its facial markings. The two animals are interacting in a way reminiscent of impala and oxpeckers: the smaller animal is picking ectoparasites off the larger and also keeping a lookout for predators. However, if the relationship is anything like oxpeckers, the small partner also sometimes sucks blood or otherwise irritates the larger.

The smallest arthropods

Did you know that the smallest eukaryotic cell is tens of thousands of times smaller than the largest? The smallest insects, a family of egg-parasite wasps known as fairyflies, are smaller than an average Paramecium; the former is made of tens of thousands of cells, while the latter is a single cell. Due to the huge difference in scale, these cells function very differently, and fairyflies and other microscopic arthropods (the group including crustaceans, arachnids, insects, and other hard-exoskeletoned, jointed-legged creatures) have had to make a lot of sacrifices in order to get so tiny.

Many of the smallest organisms are parasites, including all viruses, the smallest bacteria, and the smallest insects. Why? Because to parasitize a host, it helps to be smaller than that host–and as hosts shrink for the same reasons as the aforementioned pumpkin toadlets, parasites have to also miniaturize in order to take advantage of those resources. Someone’s gotta do it! Furthermore, due to the parasitic lifestyle, a lot of things that would normally be constraints don’t come into play, allowing the parasite to jettison certain functions. For one, animals operating at the very lowest possible size limit have to have eggs and/or young that are still smaller. The smallest arthropods all only create and lay one enormous egg at a time: the females of the non-parasitic mite genus Brachychthonius are 180 microns (µm) long, and they lay 100µm eggs! But in parasites and parasitoids (parasites whose actions result in the death of the host, a lifestyle intermediate between parasitism and predation, like wasps who lay eggs inside caterpillars), it’s much easier for the young to find food, since they are surrounded by it, so they don’t need to be as anatomically or behaviorally capable as the young of non-parasites. Fairyflies take this to its logical conclusion and inject their eggs into other eggs, which allows their egg to be extremely small and simple–basically just the embryo, with no in-egg nutrition.

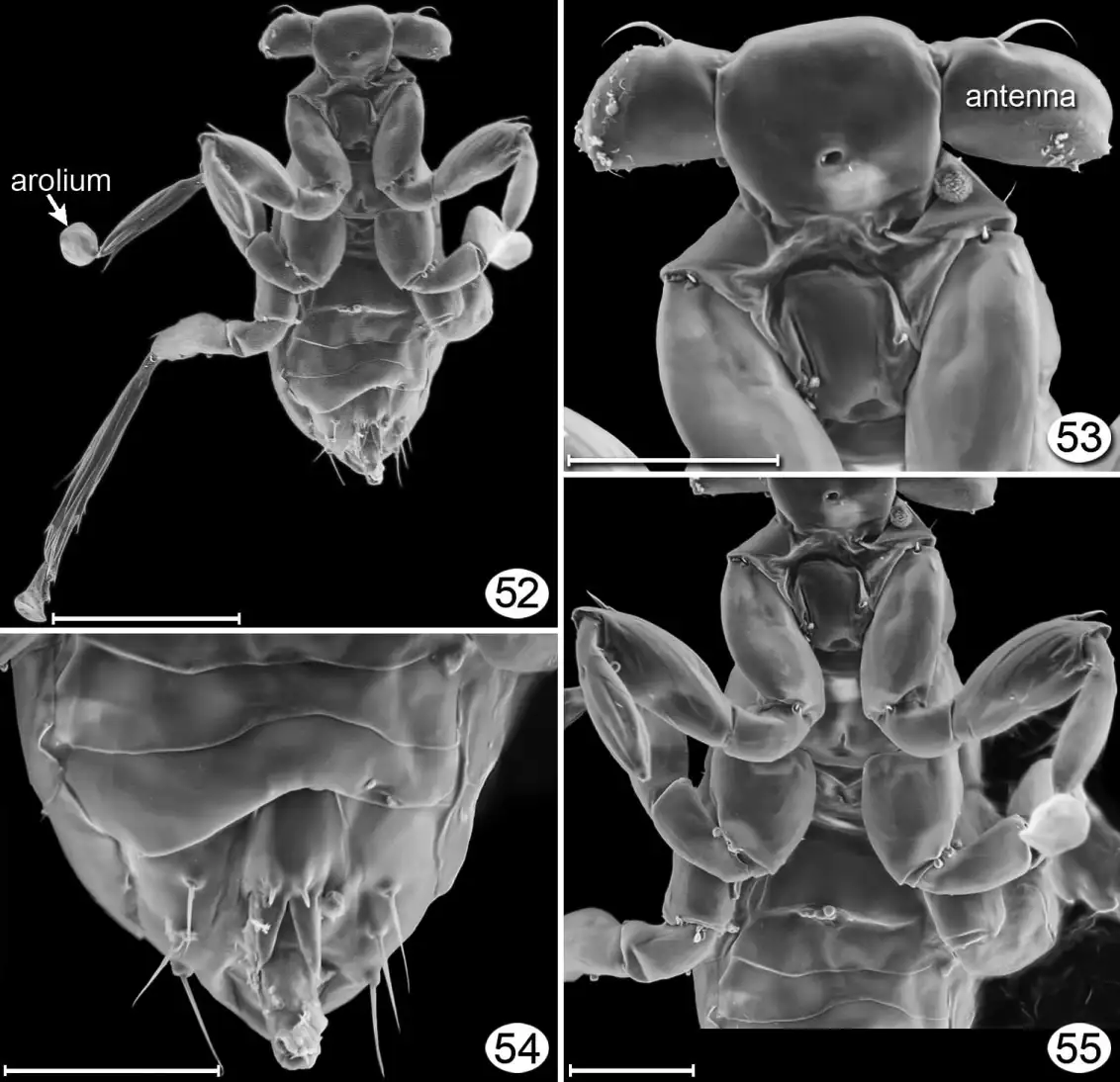

Some tiny arthropods do very weird things to reproduce. The fairyfly Prestwichia injects multiple eggs into the host egg, and the wingless males copulate with the females while still inside. Only the female has wings and a mouth, and will go out into the world to find more host eggs. In the very smallest genus of fairyfly, Dicopomorpha, the male is eyeless, wingless, and mouthless, and has reduced antennae and suction cups for feet. His one purpose is to suction onto a female, mate, and die.

Even stranger is the mite Adactylidium, which eats a single egg of a thrips (a tiny (1mm or less) herbivorous insect) but doesn’t inject eggs into it. Instead, it is pregnant with one son and multiple daughters, and the son mates with all the daughters while still inside the mother. The daughters, now pregnant with their own single son and multiple daughters, then eat their way out of the mother and go find more thrips eggs; the son emerges from the mother as well but only lasts a few hours.

Because eggs and young have to be a certain minimum size, in many tiny creatures the females are much larger, and often more bodily complex, than the males. This is part of what’s known as Rensch’s Rule: that, after accounting for evolutionary history, in smaller animals the females tend to be larger, while in larger animals the males are larger. In species large enough for the stresses of pregnancy not to be the driving force behind female size, the males’ large size is driven by sexual selection. However, as with all biological rules, there are exceptions. In some minute insect species, the males can either grow up small and “degenerate”, or they can get almost as large as the females, complete with eyes and wings. It’s unknown what causes them to develop in one fashion or the other. [5]

Since there are many genera of fairyflies that independently achieved the same tiny size–Alaptus, Megaphragma, and the colorfully named Kikiki and Tinkerbella, to name a few–it appears that this is the lower limit for insects. Why are mites able to break the 100-micron barrier when insects can’t? Because mites lead a much simpler lifestyle. Mites are often herbivores that disperse by wind, while insects must actively fly around and look for food. Tiny mites have reduced the number of segments in their legs to one or two, and don’t have extensor muscles in their legs, only flexors. To extend their legs, they flex a body muscle that puts the limb under hydrostatic pressure. They also often only have two legs, plus a suction cup on the tail, although some have four legs. Even the smallest insects retain the standard six multi-segmented legs, and have the normal arrangement of opposing leg muscles for extension and flexion. Insect legs need to be able to jump, in order to let the first wing stroke clear the ground to get airborne, and then they need to be able to tuck during flight. [6]

Tiny insects have made important anatomical sacrifices as well, though. Both fairyflies and the smallest non-parasitoid insects, featherwing beetles, have done away with hearts, since at that scale diffusion is sufficient to transport nutrients around the body, and females have only one ovary. More strangely, adult fairyflies’ neurons lack nuclei; as a larva, their brain can spill out of their head into the rest of their body, but adult wasps have, well, wasp-waisted necks, forcing their brain to contain itself in the head. To deal with this, they produce enough proteins as larvae to last the rest of their five-day lives, and during metamorphosis they resorb the nuclei. This indicates that brain size is probably another limiting factor on miniaturization–behavior of a certain complexity demands a minimum number of neurons, and neurons have a minimum size, dictated by the axon’s ability to transmit signals and the amount of DNA that needs to fit in the cell body. Featherwing beetles haven’t figured out this fancy nucleus-deleting trick, so the nuclei of their neurons takes up 90% of the cell body’s volume. [7]

(If you’re interested in the largest possible neurons, check out this blog post by Sauropod Vertebra Of The Week.)

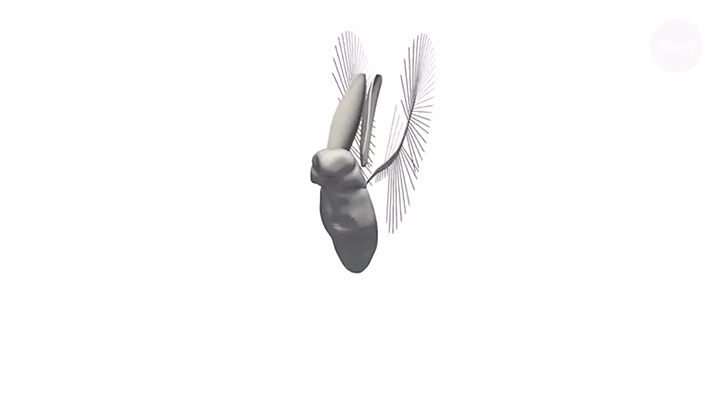

Another phenomenon that works very differently at small scales is flight. As you may have guessed from their name, featherwing beetles (and fairyflies too) have wings that look like feathers: a thin, solid central portion with long hairs sticking out to the sides. This is because at small scales, very little lift is needed to keep the animal aloft, but moving a big flat paddle through the viscous, low Reynolds number air is a lot of work. Even so, there’s still variation in how feathery the wings are: one fairyfly, Trichogramma, has pretty wide wings with short fringes, while another, Kikiki, has extremely narrow wings with long fringes. In addition to the funny wing shape, these tiny insects also employ a different flight style, known as “clap-and-fling”:

They hold their body vertically and tread air with their wings, which clap in both the front and back. Featherwing beetles also move their wing casings in the opposite direction of the wings to hold the body steady. [8]

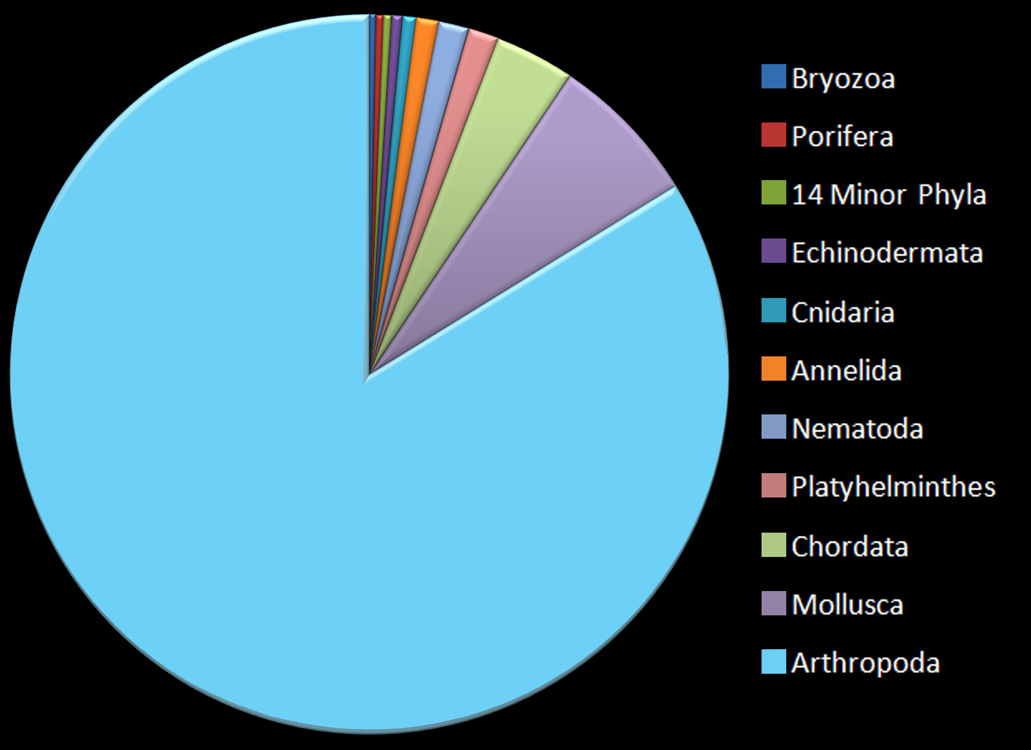

Also–did you know that over three-quarters of all animal species are some kind of arthropod? Check out this pie chart:

We chordates (animals with a backbone) are doing pretty well, in third place (the green segment). Molluscs have us beat, but only by a little. But next to arthropods, there’s just no contest. They have the most species diversity by miles! If you thought humans ruled the world, think again…

The largest viruses

And now for something completely different–instead of discussing the smallest members of large-bodied animal groups, we’ll take a look at the largest members of the smallest-bodied group: viruses. PBS Eons has a great episode on this, if you prefer video. I’ll go just a bit more in depth here.

Viruses are the tiniest biological things out there, and are often considered to be not truly alive since they’re missing a lot of the machinery for replication and metabolism that all other living things have. They’re essentially just a clump of genetic material inside a protein casing, known as a capsid; the capsid may have features that help the virus enter the host, inject its payload, or hide from an immune system, but it doesn’t have the ability make its own proteins or reproduce on its own. Most viruses are between 20 and 100 nanometers across, which is significantly smaller than the wavelength of visible light (we can see light with wavelengths between 380 (violet) and 700 nanometers (red)). This means they normally can’t be seen except with an electron microscope, since visible light just…misses them. Traditionally, viruses were thought to have arisen separately from the rest of life, perhaps in a similar manner as the RNA world hypothesis, or from plasmids–round sections of transposable genetic material–which escaped from a cell and somehow acquired an envelope.

However, there is a recently-discovered class of viruses that seems to be intermediate between viruses and the rest of life, hinting that maybe regular viruses are actually also a case of extreme miniaturization and simplification. The first one discovered, named mimivirus, short for “microbe-mimicking virus”, is a whopping 500 nanometers long, large enough to see under a regular microscope. It has a lot more genes than is common for viruses, and some of them even code for proteins used in translation, which is a process no virus, including mimivirus, can do. They can also be infected by other viruses and even have some defenses against them.

Now that we know what to look for, giant viruses of many types are turning up just about everywhere. (The second giant virus named was called “mamavirus” because it looked like mimivirus but bigger.) They’re present in essentially every environment, but mostly infect amoebae, which is another reason we didn’t know about them until recently. They weren’t clinically relevant.

If it’s true that viruses are descended from more complex, bacteria- or archaea-like ancestors, that would potentially put a fourth “domain” branch on the tree of life, a major revision. However, while the case for this is compelling, it’s far from decided. Due to the gene-swapping habits of many microorganisms, tracing their ancestry through genetics is quite messy. Furthermore, since giant viruses tend to infect amoebae, which are themselves a melting pot of all kinds of genetic material–including bacteria, archaea, plant, animal, and virus–due to their tendency to eat anything smaller than them (which, as I mentioned before, includes fairyflies and other animals!), giant viruses have have an alibi for any kind of gene they’re caught displaying. It’s also very possible that all three hypotheses are true: that some viruses originated in subsequent abiogenesis events–that is, assembled spontaneously from non-living components; some formed out of genetic material broken off from cells; and some are miniaturized descendants of other living things. If that’s the case, “virus” would become a polyphyletic group, with some belonging outside the tree of life altogether, some as a combination of tree- and non-tree elements, and some nested within existing branches. [9]

Either way, I think asking whether or not they are “alive” is a useless, pedantic pursuit, which will only get more so as nanotechnology and artificial intelligence approach life-like capabilities. It doesn’t matter what you call them–only what they’re capable of!

Just for fun

Here’s a table of tiny creatures that’s the counterpart of the one in my whale evolution post!

| Category | Smallest Known | Length (µm) | Mass (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | Circovirus | 0.017 | - |

| Bacterium | Mycoplasma (parasite of primates) | 0.2-0.3 | - |

| Archaeon | Nanoarchaeum (thermophile) | 0.2-0.5 | - |

| Eukaryote | Ostreococcus (alga) | 0.8 | - |

| Animal | Myxobolus (parasitic cnidarian) | 21 | - |

| Bilaterian | Rotifer (freshwater zooplankton) | 40 | - |

| Arthropod | Cochlodispus (mite) | 79 | - |

| Insect | Dicopomorpha male (fairyfly) | 139 | - |

| Non-parasitic insect | Discheramocephalus (feather-winged beetle) | 350 | - |

| Deuterostome | Psammothuria (sea cucumber) | 4000 | - |

| Vertebrate | Schindleria male (fish) | 6500 | 2 |

| Tetrapod | Paedophryne (frog) | 7000 | 10 |

| Amniote | Sphaerodactylus (gecko) | 14,000 | 130 |

| Mammal | Batodonoides (50-million-year-old shrew) | ~30,000 | 1000 |

| Living mammal | Bumblebee bat | 29,000 | 2000 |

| Dinosaur | Bee hummingbird | 55,000 | 2000 |

Bibliography

-

Essner, R. L., Jr., Pereira, R. E. E., Blackburn, D. C., Singh, A. L., Stanley, E. L., Moura, M. O., Confetti, A. E., & Pie, M. R. (2022). Semicircular canal size constrains vestibular function in miniaturized frogs. In Science Advances (Vol. 8, Issue 24). American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abn1104

-

Araújo, R., David, R., Benoit, J. et al. Inner ear biomechanics reveals a Late Triassic origin for mammalian endothermy. Nature 607, 726–731 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04963-z

-

Bajdek, P., Qvarnström, M., Owocki, K., Sulej, T., Sennikov, A. G., Golubev, V. K., & Niedźwiedzki, G. (2015). Microbiota and food residues including possible evidence of pre-mammalian hair in Upper Permian coprolites from Russia. In Lethaia (Vol. 49, Issue 4, pp. 455–477). Scandinavian University Press / Universitetsforlaget AS. https://doi.org/10.1111/let.12156

-

Rey, K., Amiot, R., Fourel, F., Abdala, F., Fluteau, F., Jalil, N.-E., Liu, J., Rubidge, B. S., Smith, R. M., Steyer, J. S., Viglietti, P. A., Wang, X., & Lécuyer, C. (2017). Oxygen isotopes suggest elevated thermometabolism within multiple Permo-Triassic therapsid clades. In eLife (Vol. 6). eLife Sciences Publications, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.28589

-

Grebennikov, V. V. (2008). How small you can go: Factors limiting body miniaturization in winged insects with a review of the pantropical genus Discheramocephalus and description of six new species of the smallest beetles (Pterygota: Coleoptera: Ptiliidae). In European Journal of Entomology (Vol. 105, Issue 2, pp. 313–328). Biology Centre, AS CR. https://doi.org/10.14411/eje.2008.039

-

Huber, J., & Noyes, J. (2013, April 24). A new genus and species of fairyfly, Tinkerbella nana (Hymenoptera, Mymaridae), with comments on its sister genus Kikiki, and discussion on small size limits in arthropods. Journal of Hymenoptera Research; jhr.pensoft.net. https://jhr.pensoft.net/articles.php?id=1635

-

Polilov, A. A. (2011). The smallest insects evolve anucleate neurons. In Arthropod Structure & Development. Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asd.2011.09.001

-

Miller, L. A., & Peskin, C. S. (2005, January 1). computational fluid dynamics of ‘clap and fling’ in the smallest insects. The Company of Biologists; journals.biologists.com. https://journals.biologists.com/jeb/article/208/2/195/15804/A-computational-fluid-dynamics-of-clap-and-fling

-

Colson, P., Scola, B. L., Levasseur, A., Caetano-Anollés, G., & Raoult, D. (2017, April 1). Mimivirus: leading the way in the discovery of giant viruses of amoebae - Nature Reviews Microbiology. Nature; www.nature.com. https://www.nature.com/articles/nrmicro.2016.197