Recently, I’ve been getting more good questions from friends and family that I think deserve to be answered on the blog. However, a lot of them aren’t really long enough to justify their own posts. So, in this post, I’ll do a little Q&A–if you have more questions, feel free to email me at obscure.dinosaur.facts@gmail.com and ask! I’ll append my answers to this post.

I’ve answered a few longer questions in other posts in the past. Find those here:

1. How do scientists decide if something is a new species or not?

The core of the process is comparing autapomorphies, or unique features, between the bones of the new specimen and those of the most closely related existing specimens. For example, in the description of the new tiny ornithodiran, Kongonaphon kely, the paper places it within a family (Lagerpetidae) by describing the unique shape of the thighbone shared by members of that family. Then, it differentiates Kongonaphon from all other members of that family by listing individual differences for each one (e.g., “distinguished from Dromomeron by the presence of a sharp, blade-like fourth trochanter; distinguished from Lagerpeton by the fourth trochanter angled medially…”).

However, this is just the tip of the iceberg. One also has to take into account ontogeny (is the new species just a juvenile of an existing one?), unity of material (is the new specimen a conglomeration of bones from multiple animals?), and taphonomy (are the putative unique features of the new specimen just due to being deformed during preservation?). Usually, the authors describing the new specimen can justify their position, but occasionally one or more of these factors results in a species or genus being named that is later realized to be invalid. (Read more about this in my post about junior synonyms).

Another tool for both determining whether a specimen is unique enough to warrant a new genus or species, and for figuring out what other known animals it’s related to, is phylogenetic character analysis. Here’s how it works. First, lots of photographs are taken of the specimen from all angles, and turned into a 3D computer model. Then, the model is scored based on “characters”–essentially, every little feature on the bone is categorized and assigned to one of a few valid states. For example, one character might be “skull length,” and it could fall into state 0, “less than 50% the length of the spine,” or state 1, “more than 50% the length of the spine.” The computer then figures out statistically what phylogenetic trees are the most likely (parsimonious), given all the character data for the included animals, and spits out a tree. If it tells you that your new specimen is distant enough from the next named species, you might get to name your own genus, or even family!

Reference: Kongonaphon methods

2. How can so much information be determined from bone histology (looking at thin cross-sections of bone under a microscope)?

In my other post about paleoart, I wrote about how you can infer all kinds of information about an animal’s biology from looking at a small cross-section of bone under a microscope, including metabolic rate, gender, age, and more. Here’s how that works!

Warm- or cold-bloodedness. The density of osteons (blood vessels running through bone) is strongly correlated with resting metabolic rate. If you slice a bone in half the short way and count the number of little vein rings per unit area and plug that and the phylogenetic tree information into a certain statistical package, it will spit out an estimated metabolic rate for the animal in question. The model was built and refined using bones from living animals, whose metabolic rates are directly measurable.

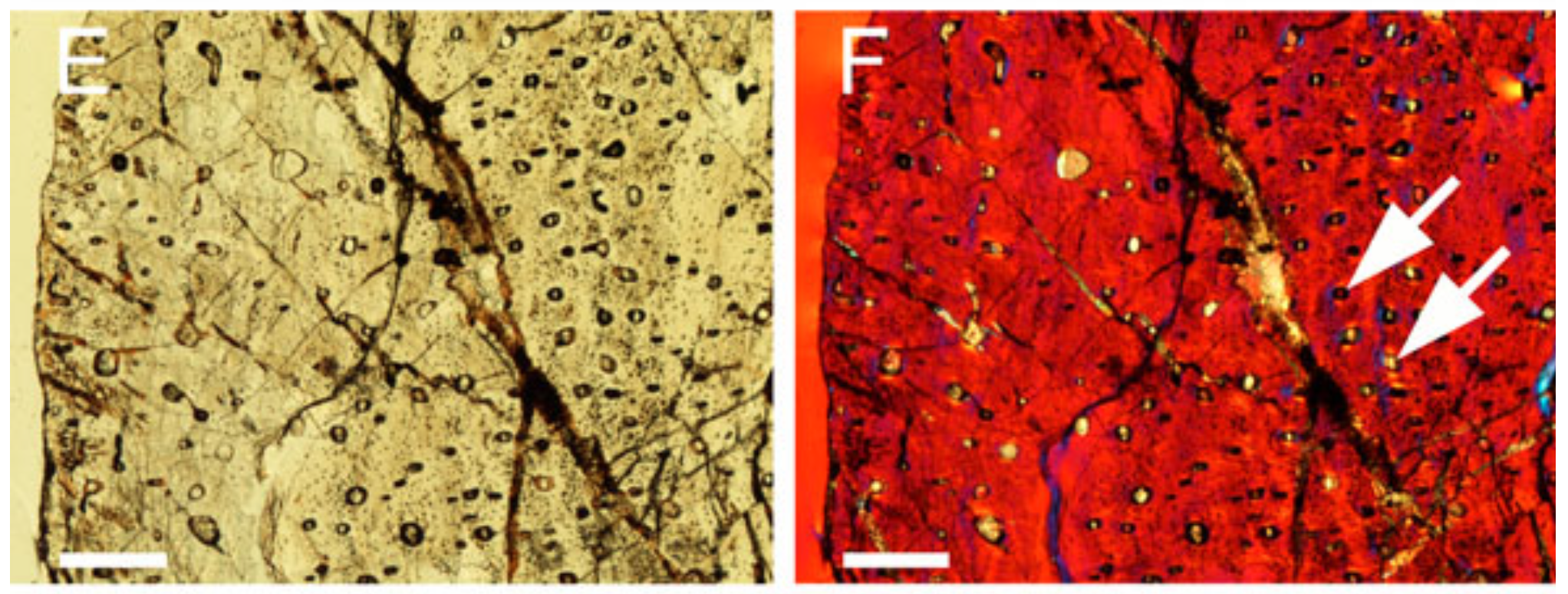

This is a slice of the tibia (shin bone) of Azendohsaurus, a Triassic archosauromorph (early relative of crocs and birds) that was recently found to be warm-blooded using this method. In the study, the researchers compared slices of the humerus (upper arm bone), femur (thighbone), and tibia and obtained similar results from all three bones.

Reference: Azendohsaurus methods

Bone structure and function overview

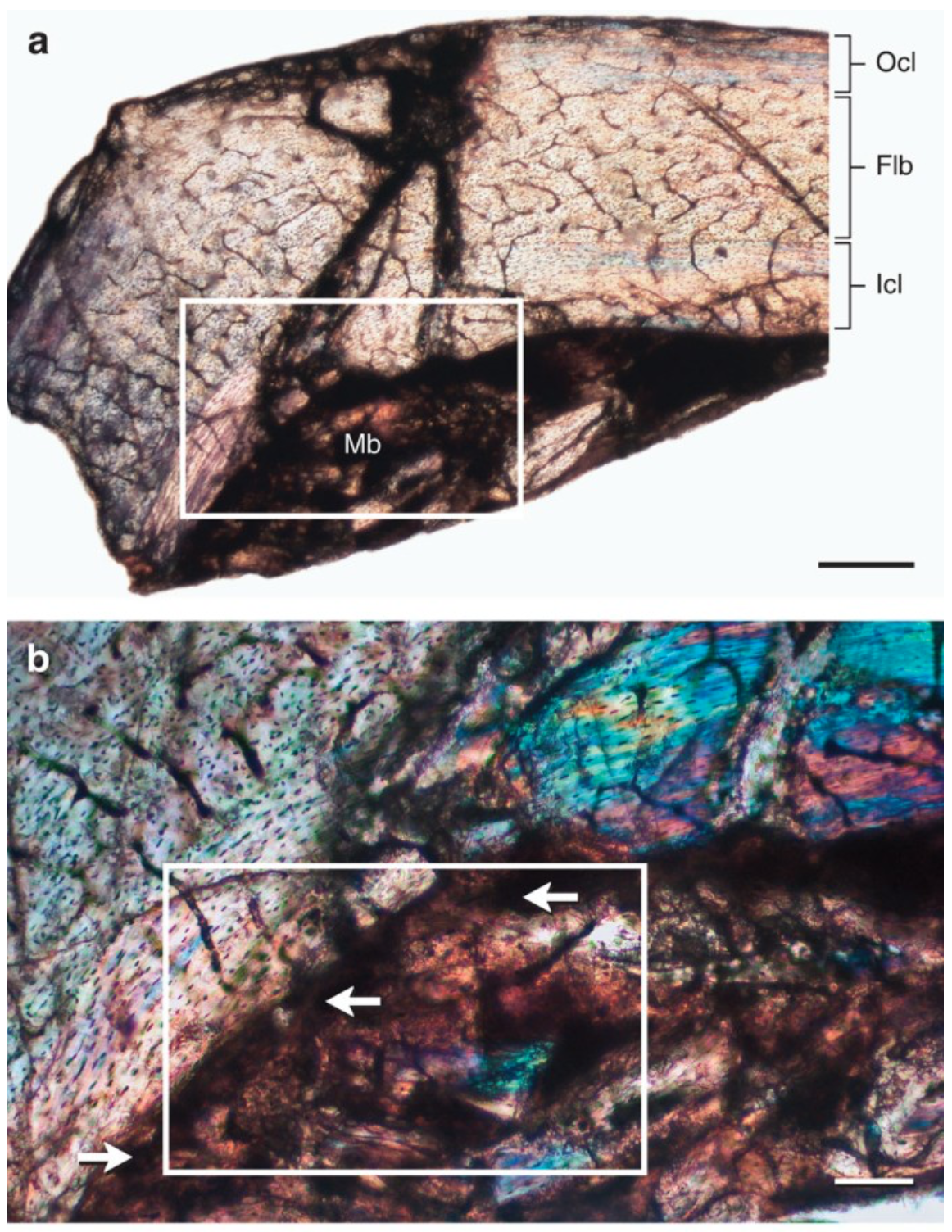

Gender. The technique that elucidates gender from bone histology only applies to dinosaurs that lay hard-shelled eggs, including birds. Since producing eggshells requires lots of calcium, a dinosaur mother would build up deposits of medullary bone, a distinctive type of spongy bone, in her arm and leg bones in preparation for laying eggs. If medullary bone is present in a specimen, it’s definitely a female, and if enough female specimens are known, the menstrual stage of an individual can be deduced from the thickness of the layer.

This is a section of the humerus (upper arm bone) of the Early Cretaceous bird, Confuciusornis. The dark area labeled “Mb” is the medullary bone, and the white arrows indicate locations where the medullary is attached to the neighboring bone layer.

Reference: Confuciusornis study

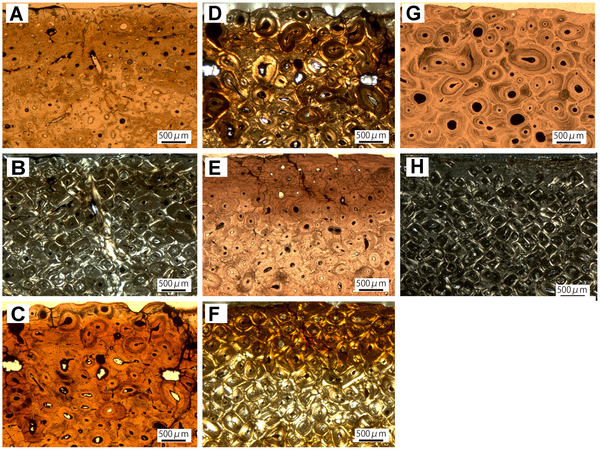

Age. In many animals, bone growth doesn’t happen at a constant rate, but slows or stops seasonally. If you look at a cross-section of the bone, you can literally count rings, like in a tree, which correspond to years of age.

Back to the example with Kongonaphon, the little Triassic basal ornithodiran. This is a cross-section of its tibia (shin bone), with arrows indicating lines of arrested growth (LAGs).

However, it’s not always simple. As animals grow, they often remodel their bones from the inside out. Older tissue can be resorbed, erasing the growth lines and leading to underestimates of age. Also, not all animals have these lines–most mammals and birds, and some dinosaurs, do not.

Growth rate. This is a bit harder to quantify through bone histology, and easier to study through comparison of specimens in different life stages. However, if you only have one specimen available, you can get a general idea of growth rate by comparing bone type: fast growth is indicated by woven, light bone with large blood vessels, while slow growth is indicated by parallel-fibered, dense bone with small blood vessels.

Above, A and E show slow-growing parallel-fibered bone, while C and G show faster-growing woven bone. The rest of the views are repeated under cross-polarized light (i.e., B is looking at the same thing as A but under different lighting). These bone sections are from different specimens of nodosaur (the stocky, armored dinosaurs without club tails) of varying ages.

Reference: Ankylosaur growth rate study

3. Could Jurassic Park be real?

Short answer: no.

Long answer: DNA is a very delicate and complicated molecule. When an animal is alive, its cells are constantly working to keep the DNA in good repair, and after death, since these processes halt, the DNA starts to degrade, due to rotting, UV damage, mineralization, etc. So far, the oldest ancient DNA that has been recovered was from a 700,000 year old horse, but it’s estimated that under ideal conditions, ancient DNA could be sequenced from a specimen up to 1 million years old. However, beyond that, the DNA would be too degraded to be read. The last non-avian dinosaurs went extinct 66 million years ago, so obtaining DNA from their fossils would be impossible.

There’s another approach that pushes the window a little further back: ancient proteomics. Since DNA codes for the manufacture of proteins, and since proteins survive a bit longer in fossils than DNA itself, if scientists can find out what proteins are in a specimen, they can work backward to deduce at least some of the DNA sequences in its genome. This approach has been applied to a 1.77-million-year-old rhino tooth, now the record holder for oldest (indirect) known ancient DNA. However, even under the best conditions, proteins are only expected to last 2-3 million years, so non-avian dinosaurs are still far out of the question.

4. Why is there so often a sizeable gap between a dinosaur genus’s discovery date and its publication date?

For example, the little red nodosaur Borealopelta was dug up in 2011, but the paper naming it was published in 2017. The usual reason for this delay is that it just takes a long time and a lot of manual labor to prepare a fossil for study. That involves first removing the bones from the matrix, or sediment, that they’re surrounded by: first, they’re excavated in big blocks from the ground and put into plaster jackets before moving them to the lab where they’ll be prepared. Then, much of the matrix is mechanically removed with jackhammers and grinders. Then, small mechanical work is done under a microscope with dental tools and brushes. After that, the fossil is strengthened and cleaned using various chemical baths of acid and resin. Only after all that are the bones ready to be studied, which also takes a lot of time and additional work.

However, prep time is not the only reason for a fossil’s publication getting delayed. In the case of Beibeilong, the giant oviraptorosaur preserved as a fetus in an egg, the fossil was unearthed by fossil poachers sometime in 1992 or 1993, and sold to a collector, and then resold to a museum in Indiana, where it was on display for years. When scientists finally learned about it and wanted to study it, they still could not until it was returned to China, due to its dubious legal status. It was finally named and described in 2017, 25 years after its initial discovery.

Twenty-five years is a blink of an eye compared to how long it took Effigia to be described after its exhumation in 1947. This was a crocodile relative that was found in a bonebed containing dozens of specimens of the dinosaur Coelophysis. Since Effigia was about the same size and shape as Coelophysis, and there were just so many specimens in the quarry, they were all packed up in plaster together and sent to storage at the American Museum of Natural History, and the fact that one was a different animal was overlooked. Only in 2006, when intrepid grad student (now renowned dinosaur researcher) Sterling Nesbitt went around opening the plaster jackets, was the fossil described, 59 years later.

5. How do you learn and remember all these dinosaur names and clades?

When I first started getting into dinosaurs, I created a spreadsheet called Dinosaur List, because I’m a spreadsheet fanatic. I listed dinosaur genera that I came across by family and by time period, and included some sparse notes. This soon expanded to include non-dinosaur ancient creatures and other eras besides the Mesozoic (“Age of Dinosaurs”) too. The way I decided what to put on the list was by trawling Wikipedia, finding and following lots of paleoartists I liked, reading books, and listening to podcasts (for specific recommendations, see my post on that topic). Then, once the list became long and unwieldy, I started picking an animal off the list each day to do a little more in-depth research on and write up a little summary. I think doing that is what made things stick a lot better–homework works!

The blog actually grew out of my dinosaur-a-day summaries. I told some friends what I was doing and they suggested I post it where others could see, and they bought me the domain name obscuredinosaurfacts.com. I’ve also learned a ton by doing the necessary additional research to write all the content that’s on there now. I think the quality of my writing has changed a lot since the beginning–it’s gotten a lot more rigorously researched, lengthy, and maybe less approachable, though I try to keep it as accessible as possible. No matter how much you’ve read and learned before, it’s always a learning process!

Note: The page image is a simplified skeletal diagram of Graciliraptor floofing itself against a drizzle. You can see the outside view in my Summer Art post. I chose this to be the page image because scientists can use biomechanical modeling, both computerized and old-fashioned clay and wires, to determine what postures a fossil animal could’ve taken. Sometimes these postures result in a shape we wouldn’t expect based on just looking at the skeleton. Here are some fun examples: birds mammals both