Venturing outside the realm of Mesozoic reptiles, here’s an overview of the mostly-Permian early diversity of our own lineage, the synapsids. The Permian Period (299-252 million years ago) was the last period of the Paleozoic Era, and was characterized by dry weather, falling oxygen level, and shrinking forests due to the formation of the supercontinent Pangea, which put more landmass away from the coasts. This was bad for the amphibians (they need water sources to lay their eggs in and keep their skin moist) and arthropods (they depend on high oxygen partial pressure to passively breathe) that had up til then dominated terrestrial ecosystems. The amniotes (reptiles, mammals, and their relatives) quickly moved to pick up the slack, and it was the stem-mammals that diversified and dominated the most during that time. The Permian was sort of like a preview of the later Age of Mammals.

In this post, I’m going to cover the main groups of stem-mammals, with pictures of characteristic or charismatic representatives along the way. Like the pterosaur and pseudosuchian family trees, the mammal tree consists for the most part of groups that peel off the “main” branch, rather than lots of bifurcations in each branch, a la the dinosaur tree.

Synapsida

Mammals and their relatives are part of the group known as synapsids (meaning “together arch”), which is the sister clade to sauropsids (meaning “reptile face”), which includes reptiles and their relatives. Together, synapsids and sauropsids make up the amniotes, or animals with a waterproof egg.

Early synapsids were cold-blooded, scaly beasts that looked a lot like modern lizards, so people used to call them “mammal-like reptiles.” This is misleading because they aren’t really reptiles (all reptiles are sauropsids); rather, they had features that we usually associate with reptiles. Even more confusingly, a lot of early synapsids are named things that end in -saurus or -suchus, which mean “reptile” and “crocodile,” respectively.

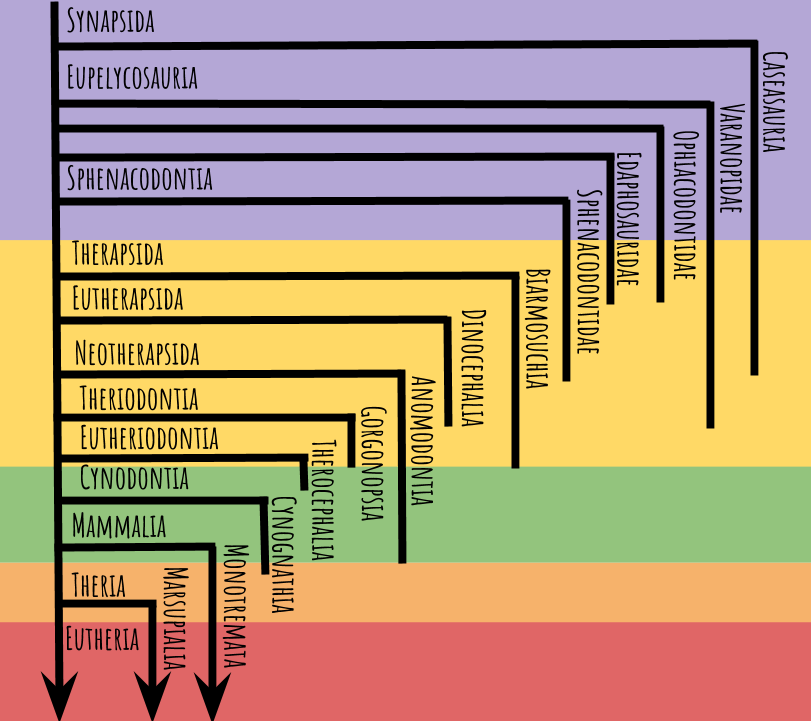

Here’s the tree we’ll be working with:

The colored bands of purple, yellow, green, orange, and red represent the Carboniferous, Permian, Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods, respectively (not to scale). Where a line ends, that group has gone extinct, and arrowheads indicate groups that are still alive today. Note that many animals fall outside these groups, but in this post we’ll just look at the most diverse and charismatic clades.

The Carboniferous Period

The Carboniferous is when the mammal and reptile lineages diverged. Both groups stayed relatively small-bodied until the very end of the period, living mostly in the shadow of the giant bugs and amphibians that ruled the scale-tree rainforests. However, toward the end of the Carboniferous the rainforests began to shrink, in an event known as the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse, which reduced the prevalence of suitable habitats for amphibians and arthropods and spurred amniote diversification.

Caseasauridae

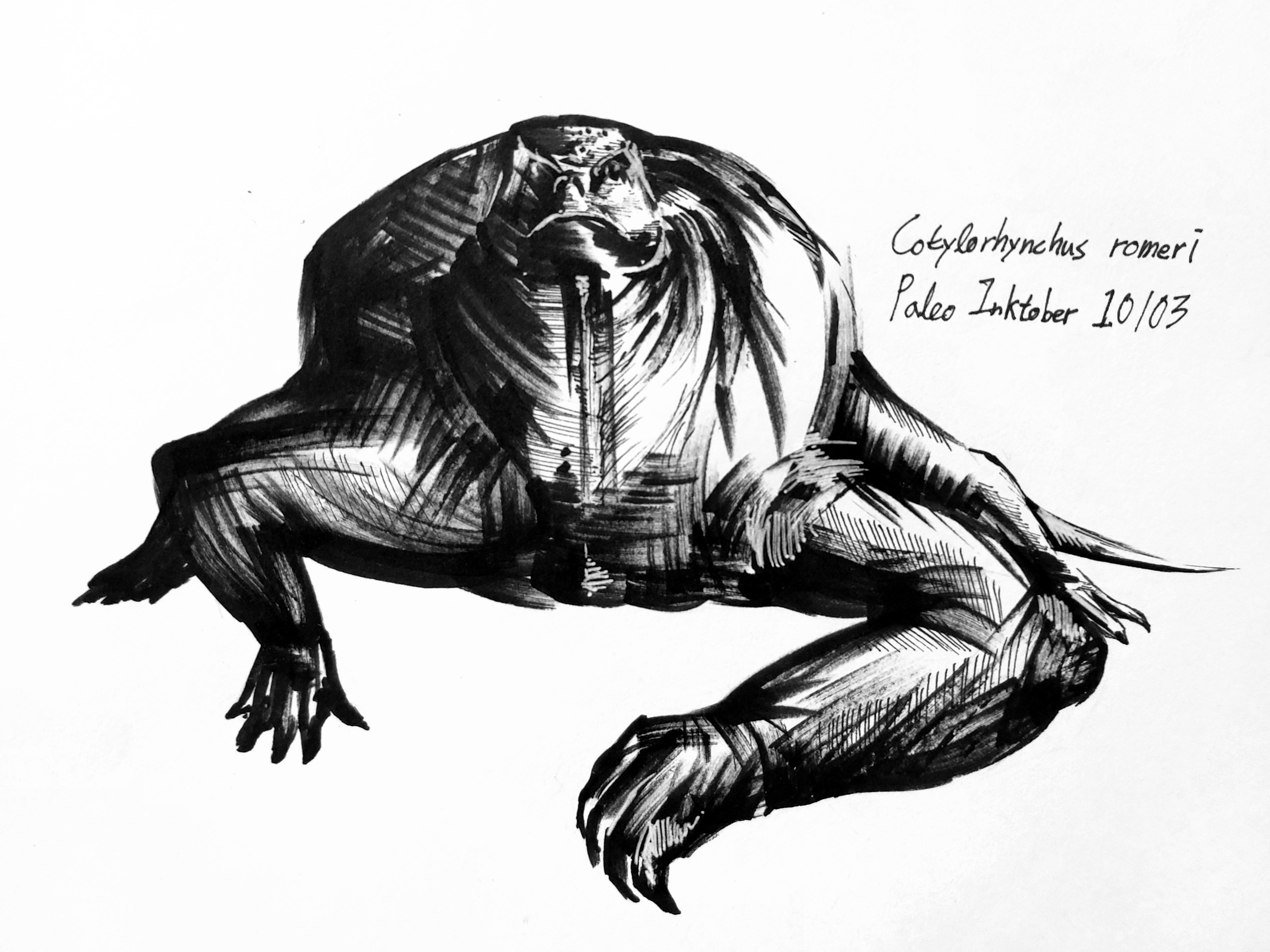

The first branch to split off within Synapsida is that of the caseasaurids. These included some lizardlike members such as Eothyris, as well as the very odd, tiny-headed, big-bodied caseids including Cotylorhynchus.

Above: Cotylorhynchus, the most famous of the caseasaurids. It was a rhino-sized herbivore with a ridiculous tiny head. This art is by my paleo Inktober friend, u/jupiter1390, on Reddit.

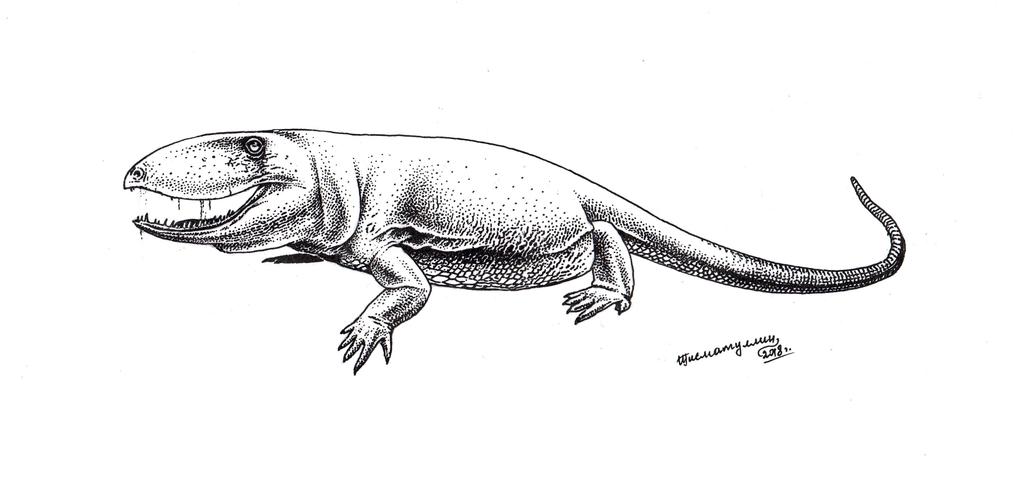

Above: Eothyris, a lizardlike insectivorous caseasaurid.

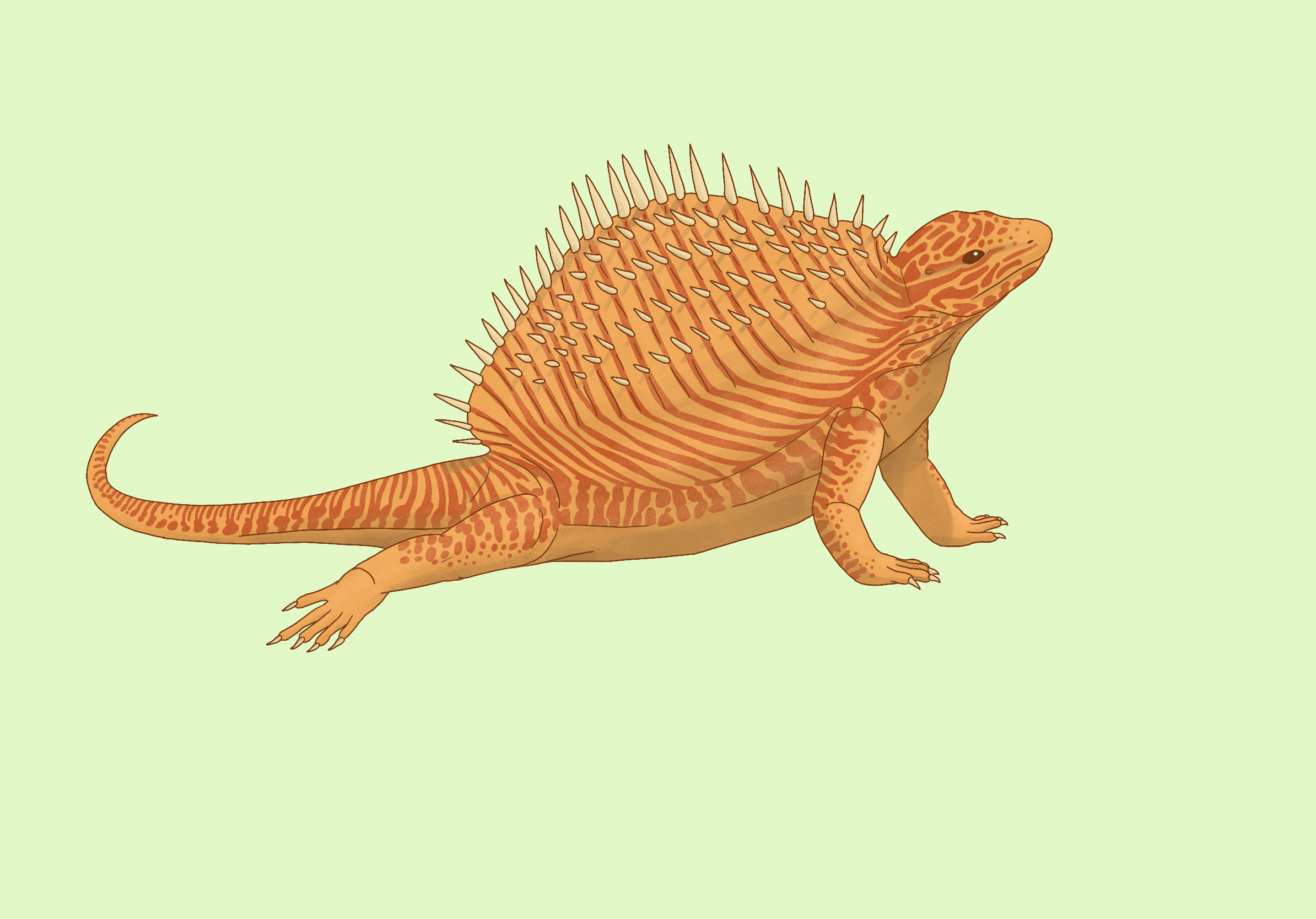

Varanopidae

The next branch we’ll look at is somewhat contentious: the monitor lizard-like varanopids, a family of small carnivores or insectivores. The jury is still out on whether they are truly synapsids, or if they’re actually sauropsids. This far back on the amniote family tree, the groups are still pretty similar!

Above: Dendromaia, meaning “tree mother,” a famous varanopid discovered with her tail wrapped around her baby inside a tree stump den. It’s the oldest direct evidence of parental care in the fossil record.

Ophiacodontidae

Ophiacodonts were another group of lizardlike early synapsids.

Above: Ophiacodon, a large predatory ophiacodont that possibly could reach weights of up to 230 kilograms. These guys were some of the biggest animals in their environment at the time.

Edaphosauridae

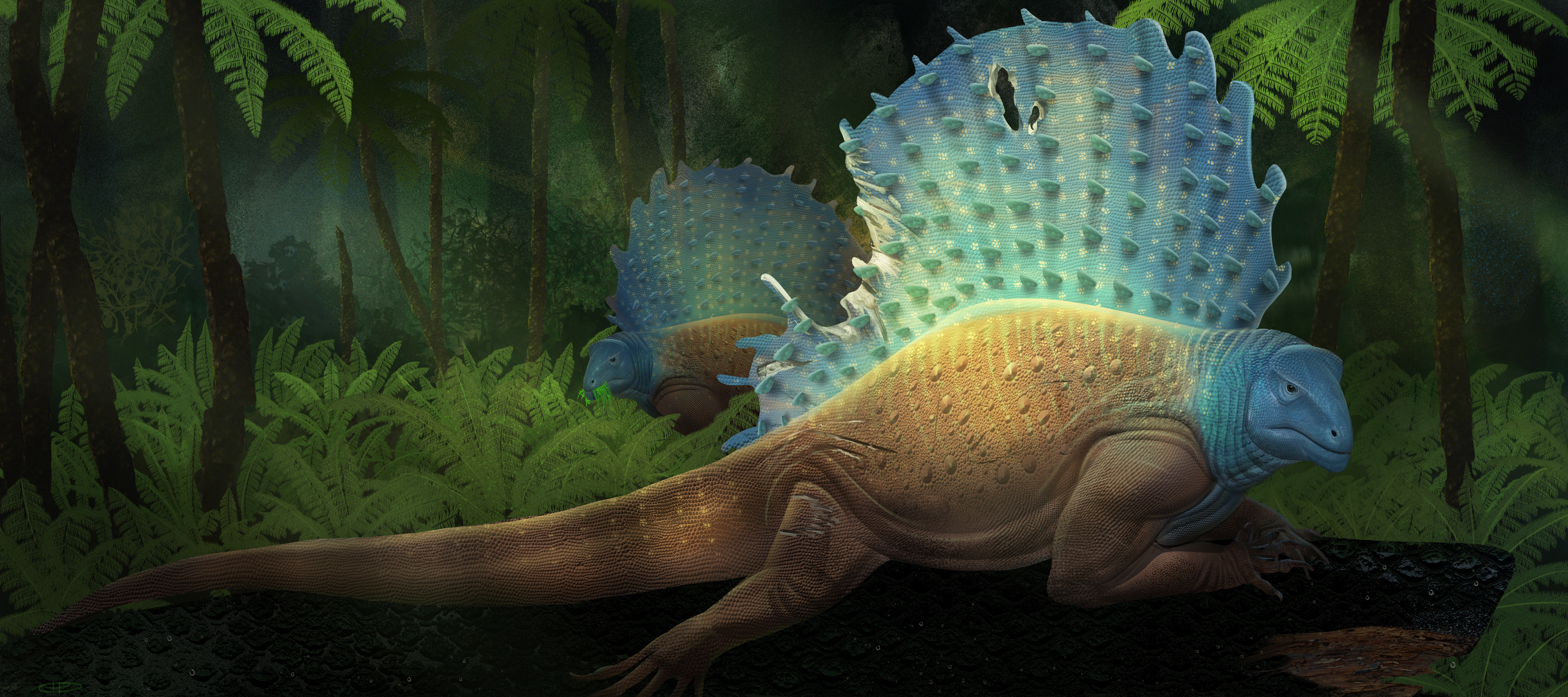

Finally, we’ve reached a group some people may have heard of! It’s the herbivorous sail-backed edaphosaurs (meaning “pavement reptile”). Unlike the carnivorous sail-backed sphenacodonts, which we’ll discuss in a moment, edaphosaurs had cross-beams on the tall neural spines that supported the sail, possibly creating a really thick sail or supporting spiky protrusions. We still don’t know what the sails were for, but the main theories are thermoregulation (large surface area for sunbathing, probably highly vascularized for shedding heat), fat storage, and display.

Above: Ianthasaurus, a small primitive edaphosaur that was only a couple feet long.

Above: Edaphosaurus, the most famous of the edaphosaurs. This big boy could reach weights of up to 300 kg, and had specialized “dental pavement” (essentially huge sandpapery molars made up of smaller teeth fused together) for chewing vegetation, from which the group gets its name.

Sphenacodontidae

This is one of the most famous groups of stem-mammals: the large, sail-backed, carnivorous sphenacodonts. These were the top predators in the Late Carboniferous and Early Permian, and included the famous Dimetrodon, a charismatic animal often included in dinosaur toy sets but is definitely not a dinosaur. Some features of the sphenacodont skull look sort of convergent with cats, and this along with their phylogenetic affinity to mammals has led some people to depict them as furry, high-walking “catmetrodons” like the below reconstruction:

Similarly to the edaphosaurs, the jury is still out on whether the sail was a fatty hump, a display structure, or a thermoregulatory device. Here’s an interpretation that takes the opposite approach as the above, depicting Dimetrodon as much more reptilian, with a sprawling gait, crocodile-like scales, and a thin webbed sail.

I think a middle ground is the most likely. Despite their close relationship to furry mammals, pelycosaurs were still cold-blooded, meaning they wouldn’t’ve needed a fur coat for keeping warm; however, that doesn’t mean they were capable of producing reptilian armor. The sail, regardless of whether it was fat or thin, thermoregulatory or not, would have been a striking feature, and thus at least part of its function must have been display. Research on osteological correlates and healed injuries in Dimetrodon’s neural spines suggests that the very tips of the spines were not embedded in the sail, so the half sail shown in the first depiction is not accurate.

The Permian Period

In the Permian Period, stem-mammals really hit their stride and diversified into an abundance of shapes and sizes. We’ve entered the area of the tree known as Therapsida, in which the stem-mammals start to get a lot more reminiscent of mammals and less lizard-like.

Note that many of the abovementioned groups also had members that survived into the early to middle Permian.

Biarmosuchia

Biarmosuchians were a group of slightly more mammal-looking carnivores that came in small-dog to large-dog-sized forms, all of which were very rare in their environments. Nearly every biarmosuchian taxon is monotypic, or known from only one specimen. Some had large eyes, indicating nocturnality, some had saberlike canines, and some had strange horny bumps on their heads.

Above: Eotitanosuchus, a large biarmosuchian from the middle Permian.

Above: Proburnetia, a small biarmosuchian from the late Permian. Bony bosses on the skull seem to be a stem-mammal or early-mammal thing–the group of biarmosuchians known as burnetiids, many dinocephalians (more on them later), and, returning after the end-Cretaceous mass extenction, the uintatheres all sported strange skull ornamentation.

Dinocephalia

The dinocephalians (meaning “terrible head”) were a very diverse group of large stem-mammals from the middle Permian. Some were huge, longish-necked herbivores, kind of like a mammal trying to be a sauropod before it was cool (such as Moschops, which inexplicably had a British stop-motion TV show made about it); some were large carnivores like Titanosuchus and Anteosaurus, which could reach weights of up to 600 kg; and some were large, sort of boarlike omnivores, such as the long-snouted Jonkeria. Dinocephalians may have been on their way to endothermy (warm-bloodedness) just due to their massive sizes–due to the square-cube law, a big animal has a harder time dissipating heat than a small one, a phenomenon known as gigantothermy.

Above: Estemmenosuchus, one of the most famous dinocephalians, a large omnivore with funky head bumps.

Above: Anteosaurus, a massive carnivore that may have been semi-aquatic.

Above: Tapinocephalus, a two-tonne, long-necked herbivore, in a speculatively furry integument. We don’t know exactly when fur arose among mammals, but given the large size and low metabolic rate of dinocephalians, this interpretation is probably fanciful.

Anomodontia (including Dicynodontia)

The next group to branch off, the anomodonts, represent a big step toward modern mammal traits. Anomodonts were true endotherms, even the small ones, and are thus good candidates for furriness (although they evolved endothermy independently of the later eutheriodonts). They also had the simplified jaw and complex inner ear characteristic of later mammals. Up until now, all the groups mentioned would have had no external ear holes; they would have had a poor sense of hearing, mostly sensing vibrations through the ground. The neotherapsids (anomodonts and more derived clades) would have had ear holes and a better sense of hearing, though ear flaps (pinnae) wouldn’t arise until later.

The most prolific group of anomodonts were the dicynodonts, which were portly herbivores with a toothless beak bookended by two tusks (hence the name, “two dog tooth”). These came in all sizes from the rat-sized Myosaurus to the elephantine Lisowicia. You can read a more in-depth description of dicynodont lifestyle and anatomy in my Lystrosaurus profile.

Above: Diictodon, a gopher-sized burrower. New burrows preserving whole litters of these little guys in situ are being excavated right now, indicating parental care.

Above: Lisowicia, the new record-holder for largest dicynodont, could reach weights of up to six tonnes. At these sizes, even if their ancestors were fluffy, Lisowicia would’ve needed sparse hair in order to not overheat. Check out Mark Witton’s post about megafaunal integument!

Gorgonopsia

This group is probably one of the most famous of the Permian stem-mammals: the saber-toothed gorgonopsids. They were the apex predators of the latest Permian, and some reached sizes of up to 300 kg. They were arguably the first group of mammals to really do the “saber-toothed cat” thing, though they would’ve been able to replace their sabers if they broke. You can see a list of all the saber-toothed synapsids throughout history in my post about convergent evolution!

Unlike the anomodonts and the later eutheriodonts, gorgonopsids were probably cold-blooded, and thus would not have been fluffy.

Above: Inostrancevia, a lion-sized gorgonopsid, looking a lot like the Cheeto mascot.

Above: Rubidgea, a wolf-sized gorgonopsid, exhibiting bright coloration. Since tetrachromatic vision (seeing using four types of cones instead of the three or two most mammals use now) was the ancestral state, perhaps some of these Paleozoic stem-mammals would’ve been as brightly colored as today’s birds and reptiles. Stem-mammals lost much of their color-producing and color-detecting abilities during their long stint as nocturnal and burrowing animals during the Age of Reptiles.

Therocephalia

The last of our Permian stem-mammals, the therocephalians, were the closest thing we’ve seen so far to modern mammals. They were endothermic, mostly cat-sized and smaller, and had both carnivorous and herbivorous representatives.

Above: Euchambersia, a late Permian therocephalian that may represent the earliest evidence of venom in the fossil record. It had spaces in its skull for venom glands, and strongly grooved teeth that could have injected it. Venom doesn’t really seem like a mammalian thing today, but platypuses do it (albeit with their feet), and since toxins often are repurposed from digestive enzymes or antimicrobial agents, they’re really fair game for any organism.

The Mesozoic Era

The Permian Period ended with the worst mass extinction Earth has ever seen: 96% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial species went extinct. All of the groups of stem-mammals except the dicynodonts and eutheriodonts died out, along with a lot of reptile diversity as well. When the dust settled, Lystrosaurus was the only one left standing…for a few million years, until the archosaurs (crocodiles and their relatives and dinosaurs and theirs) started diversifying in the Triassic, pushing most stem-mammals into marginal, nocturnal, scavenging, or burrowing roles.

Still, it was during this time that the three major groups of extant mammals (and one more extinct group we haven’t discussed yet) diverged and diversified. While most mammals were indeed small and unassuming, eking out a living in the shadow of the dinosaurs, there was actually a respectable amount of functional diversity among Mesozoic cynodonts, as will become apparent from examples later.

Cynognathia

The last main group of non-mammal synapsids we’ll discuss are the cynognaths. These were very successful, very mammal-like animals that lived from the Early Triassic to the Early Jurassic that would have been warm-blooded and furry, but lacked earflaps and would probably have laid soft-shelled eggs.

Above: Thrinaxodon, a cynognath that was recently found “cuddling” in a burrow with the similarly-sized amphibian, Broomistega! You can learn more about that odd couple in PBS Eons’s video.

Above: A pack of Cynognathus face off against the early croc relative, Erythrosuchus.

During the great shake-up that was the Triassic Period (it was bounded on both ends by two of the Big Five mass extinctions), some cynognaths got rather large, like the sheep-sized herbivore Exaeretodon and the puma-sized carnivore Diademodon, but they were hit hard by the end-Triassic extinction and did not recover.

Mammaliamorpha

Since only a small subset of the extensive synapsid family tree is still alive today, it makes sense that the crown group would be given its own common name. Mammals, as you probably already know, include monotremes (egg-laying mammals), marsupials, and placental mammals, as well as fossil creatures that fall in between those groups on the tree of life. However, since evolution tends to be gradual and continuous, there isn’t really a bright line differentiating true mammals from mammaliamorphs. Many relatively famous Mesozoic mammaliamorphs fall between cynognaths and true mammals, like the tritylodonts, morganucodonts, docodonts, and haramiyidans, but I’ll only include a couple of the more famous examples here.

By the way, if you’re wondering which groups had ears and which didn’t, check out this handy chart!

Kayentatherium was a tritylodont from Early Jurassic Arizona that is known from an amazingly-preserved fossil of an adult with 38 babies. The babies had similar proportions to the adult, which, along with the large litter size, indicate precociality, or the ability to fend for themselves shortly after birth. This is a “primitive” characteristic–modern mammals have fewer young and spend more time and energy raising them.

Castorocauda (meaning “beaver tail”) was a rabbit-sized docodont from Middle Jurassic China. It’s known from an exquisite specimen that preserves fur and a beaver-like tail, hence the name. With its specialized traits and larger-than-a-shrew size, it bucks the stereotype of tiny, evolutionarily-stagnant burrowers that Mesozoic mammaliamorphs were long thought to be.

Arboroharamiya was a haramiyidan from Middle Jurassic China that was very convergent with later flying squirrels and sugar-gliders. It had a long, possibly prehensile tail, long fingers, and patagia, or skin membranes, for gliding. It’s another example of a recently discovered Mesozoic mammal-relative that’s surprisingly specialized.

Yinotheria (monotremes and kin)

Finally, we’ve reached the true mammals! Monotremes, the egg-laying mammals that are today represented by just one species of platypus and four of echidnas, are very rare in the fossil record and are very distantly related to other living mammals. Based on genetic evidence, monotremes probably split from therians (marsupials and placentals) way back in the Late Triassic, while the latter two groups didn’t diverge from each other until the Late Jurassic. From their scant fossil record, it seems that the earliest monotreme-relatives were platypus-like, and the echidnas diverged sometime around the Eocene. You can read more about monotreme evolution in this blog post.

Can’t spot the monotreme in this picture? It’s Steropodon, an early monotreme from Late Cretaceous Australia, in its domed burrow in the background. The dinosaurs in the foreground burrow are Leaellynasaura, a famous little long-tailed ornithopod I’ve illustrated a couple times before, and the larger ones outside are a relative of Australovenator, a large predator whose affinity is uncertain.

Theria (marsupials and placentals)

There are also a lot of fossil mammals from the Mesozoic that fall in between monotremes and therians on the tree of life, such as the famous badger-sized Repenomamus, which is known to have preyed on small dinosaurs, but this post is already ridiculously long and detailed, so I’m going to skip to the end. A majority of modern mammal diversity is found among the placental mammals, which originated in Laurasia, the northern supercontinent made up of what is now North America, Europe, and Asia. However, marsupials and their relatives used to be very diverse across Gondwana, the southern supercontinent made up of what is now South America, Antarctica, Australia, and sometimes Africa.

Above: Thylacosmilus (meaning “pouch knife”), the famous saber-toothed metatherian, from Miocene to Pliocene South America. It was more serious about the whole saber-tooth thing than most: its teeth were ever-growing, the sabers anchored above the eyes for better stress resistance, the animal’s gape was super wide, and it had this ridiculous chin that would have protected the sabers while its mouth was closed.

These two modes of mammaling coexisted separately for a long time until the continents began to separate. Gondwana broke apart rather decicively, with Antarctica drifting south and freezing, causing animal traffic to stop flowing. Laurasia, on the other hand, retained many of its connections even as the continents reached their modern positions; even Asia and North America were on-and-off connected by the Bering land bridge. When North and South America collided, forming the isthmus of Panama, and the animals migrated northward and southward in an event known as the Great American Biotic Interchange (GABI), the South American fauna was mostly replaced by the placentals from North America. It’s not totally understood why, but factors could include decreased genetic diversity among the isolated South American populations and being less adapted to a competitive environment compared with the North American ones, which were in periodic contact with Asian and European populations. The only marsupials that survived in the Americas were various types of opossum, and the only truly diverse community of marsupials survived in the still-isolated Australia.

Above: Thylacoleo (meaning “pouch lion”), a very strange, specialized marsupial predator from Pliocene to Pleistocene Australia. It used modified incisor teeth for attacking prey rather than canines, and had large thumbclaws. Early human settlers of Australia interacted with Thylacoleo and depicted it in cave paintings.

I won’t go over the lineage of placental mammals–perhaps that’s a topic for another post–but I’ll put some highlights here.

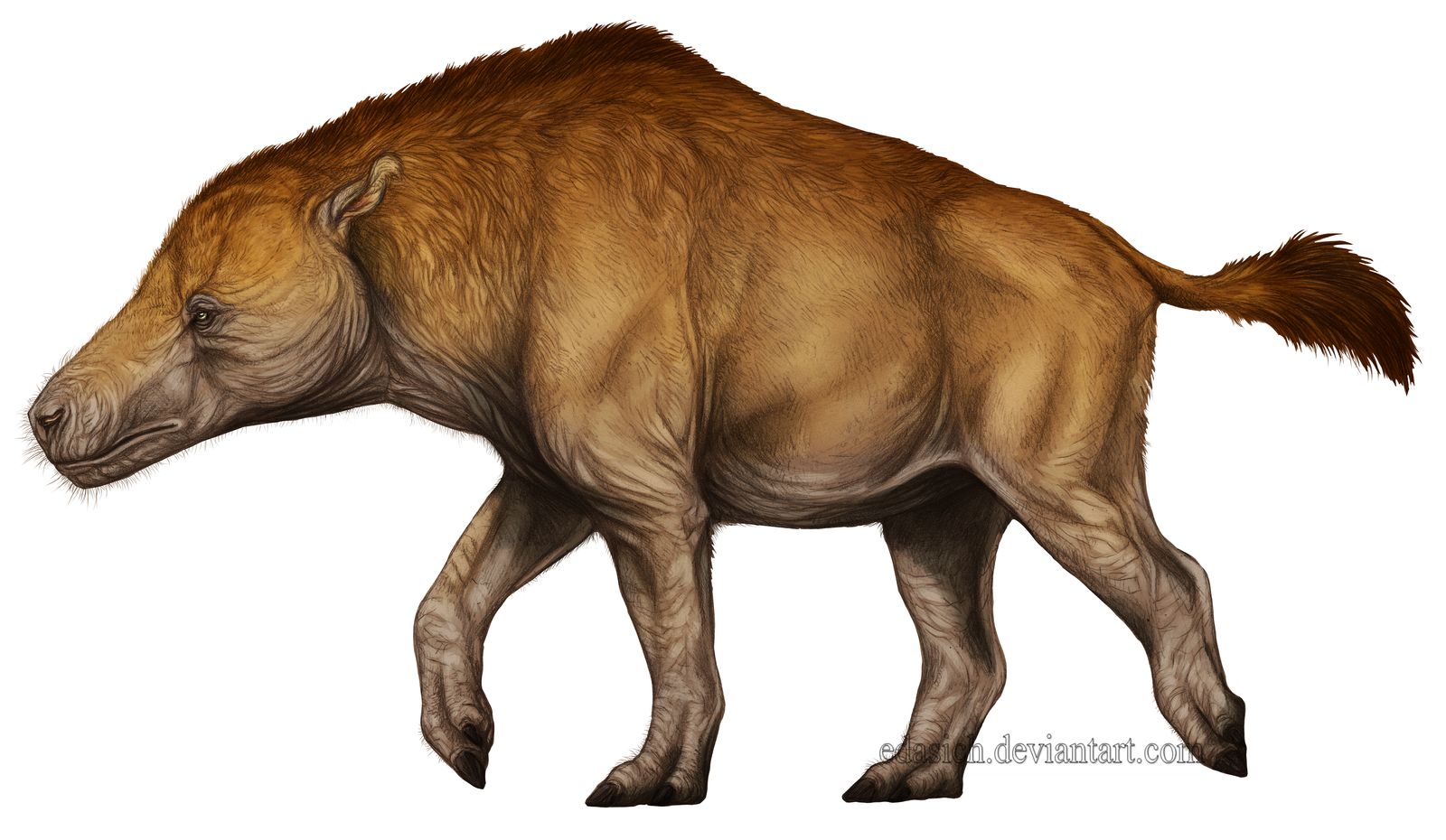

Above: Andrewsarchus, possibly the largest mammalian land predator ever, from Eocene China. It’s only known from a skull, so its affinity is unknown. Here, it’s depicted as similar to an entelodont, or “hell pig,” but it’s previously been thought to be a mesonychid or a hippo-relative.

Above: Everything old is new again! Remember Estemmenosuchus from way back in the Permian? This is Uintatherium, a dinoceratan (primitive member of the group containing horses, dogs, and everything in between) from Eocene North America and Asia, which had very similar head-boss things. Sometimes it takes me a second to remember which is from when! It doesn’t help that one group is called Dinocephalia and the other Dinocerata.

Above: The record holder for largest land mammal is Paraceratherium, a rhino relative from Oligocene Europe and Asia that could weigh up to 20 tonnes. That’s like three large elephants!

Above: Chalicotherium, from all over the Northern Hemisphere in the Oligocene to Pliocene, was one of a lineage of very weird horse relatives that had long, gorilla-like limbs adapted for knuckle-walking.

Okay, I think that’s enough extinct synapsids for now. Good job making it to the end. I hope you have a better idea of what your own illustrious forebears and their relatives were like!

Image credits: Cotylorhynchus Eothyris Dendromaia Ophiacodon Edaphosaurus Dimetrodon1 Dimetrodon2 Eotitanosuchus Proburnetia Estemmenosuchus Anteosaurus Lisowicia Diictodon Euchambersia Cynognathus Thrinaxodon Kayentatherium Castorocauda Arboroharamiya Steropodon Thylacosmilus Thylacoleo Andrewsarchus Uintatherium Paraceratherium Chalicotherium