I recently wrote another novel (again, not yet published - I’m working on that) that takes place in the Middle Stone Age of Ethiopia, 240,000 years ago (coincident with the Middle Paleolithic in Europe). I chose that setting because it offered a high density of different human species in the same time and place, but also offered a technology level high enough not to encumber the story. There are five different species of humans the protagonist encounters on her journey: Homo neanderthalensis, the strong and stocky Neanderthals; Homo naledi, a small hominin adapted for life in the trees; Homo longi, the high-altitude adapted, mysterious and elusive Denisovans; Homo erectus, the most successful and widespread human prior to Homo sapiens and the progenitor of the other species; and of course, Homo sapiens themselves. In real life, it was unlikely a single individual would meet members of all of these species, but it was theoretically possible; the world would’ve felt a bit like Middle Earth, with multiple intelligent species that could freely interbreed. Each of these human species would have led different lifestyles and practiced different cultures, none of which we can reconstruct with certainty. But given the little evidence we have from their artifacts and what we can extrapolate from their bones and fragmentary DNA, it’s a fun exercise to speculate on what they might have been like in life. In this post, I’ll describe my depictions of each of these five species, what is speculative and what is fact, and why I made some of the decisions I did.

One of the main reasons I wanted to write this book is because in most media about cavemen, they are ugly, stupid, and often only communicate only in grunts.

There’s also a glut of paleoart depicting them as horrifyingly ugly. But there’s really no reason to think they would have been ugly or unsophisticated. H. sapiens 300,000 years ago were nearly physiologically identical to humans today. With the same brains, the same hands, the same wants and needs, I think they’d have been much more similar to us than that. In my book, I may go too far to the other extreme, giving my cavemen modern morality and peaceful dispositions, but I think this is both not out of the realm of possibility and makes the story much easier to digest. If there was a bunch of rape and mutilation, no one would want to read it. The characters’ extensive vocabularies and modern slang like “cool” I’m going to hand-wave as translation convention.

Similarly to how paleoartists bridge the gap between the very dry descriptions of autapomorphies in scientific papers and the T. rex the public knows and loves, I think there’s a place for paleo-writing to educate non-experts about our ancient ancestral cousins and to get people to imagine the ways they might have lived.

Homo naledi: “treefolk”

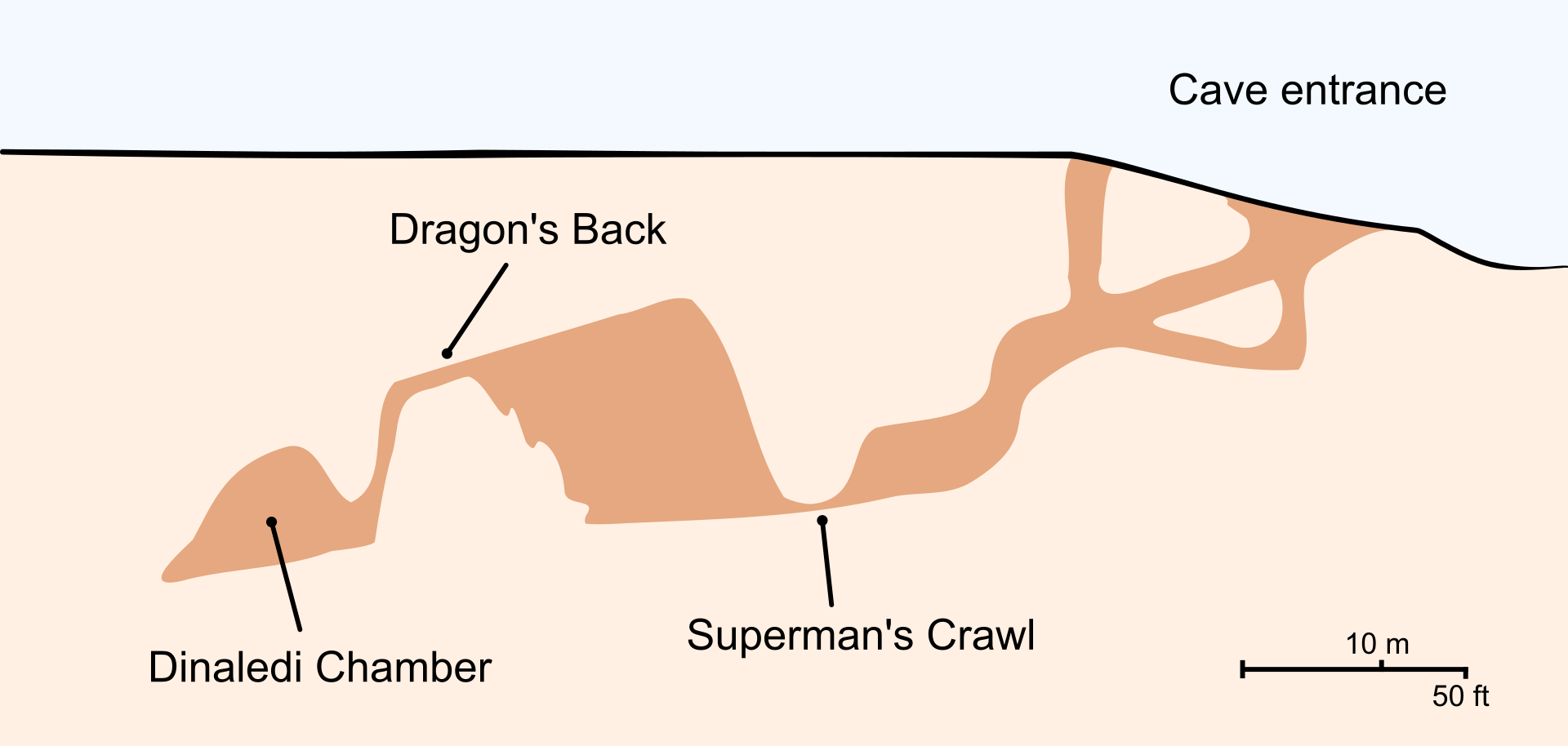

H. naledi is an interesting little hominin, standing between four and five feet tall and possessing a mosaic of basal and derived features, making it difficult to confidently place on the human family tree. There’s a cave in South Africa called Rising Star Cave that preserves the bones of dozens of individuals, only fifteen of which have so far been excavated and identified. The bones belong to hominins of both genders and all ages, from infant to elderly, and show no signs of predation, indicating they were placed there intentionally by other members of the same species. There is also evidence of fire in the cave, probably for light.

Prior to this discovery in 2015, it was generally held to be true that big brains were always better, and anytime a new, bigger-brained human species came on the scene, the older, small-brained ones went extinct. However, H. naledi’s brain size is close to that of the very earliest australopithecines, and yet it lived way more recently, surviving for hundreds of millennia alongside H. sapiens. It was therefore probably not doing the same things as our ancestors were, using different resources to avoid competition. And whatever it was doing, it was good at it.

From the numerous bones, we can reconstruct their anatomy quite well. They had narrow chests and wide abdomens, with shoulder blades situated higher on the back and further from the center than other humans, features more similar to apes. Their legs and feet were suited for walking, but not distance running the way most other hominins were. Their fingers were long and curved, which together with the wide-set arms indicate that they were good at swinging and suspending their weight from their arms, critical for life in the trees. In my book, the treefolk are graceful acrobats in the trees, but have a bit of a waddle when on the ground. They stay concealed from H. sapiens when they can, smearing themselves with mud and leaves and staying in the trees as much as possible, even living in nests of dried foliage up in the trees like birds. In my book, the treefolk live only a day’s walk from the protagonist’s kinfolk (H. sapiens) tribe, but due to their secretive practices most kinfolk have never seen one. I chose to have them be elusive for two reasons: because that’s how they survive alongside H. sapiens, and because it makes them sort of like “fair folk”, curious and mysterious and diminutive forest creatures.

H. naledi teeth are also more similar to those of apes, with big molars and dental wear indicating a diet of tough plant material. The wide abdomen may have housed a long digestive tract to break down the raw plants they consumed. In my book, they are strict vegetarians, and may even be crudivores (not cooking their food) - you don’t see them cook on the page, but since they do have command of fire, they might just do it elsewhere. Since they don’t need to eat animals, they consider killing animals to be immoral, and wear only grass skirts, while all other human species in the book wear animal skins.

Their ear bones were more similar to those of non-human apes, giving them less acute hearing at high frequencies. This is important because consonants, which are produced by pushing air through constricted lips, tongue, and throat, and are used in every H. sapiens language, fall in these frequencies. Like chimps, H. naledi would’ve been able to hear them, but not with much clarity, making verbal communication more difficult. In my book, they get around this limitation by using sign language, which is hypothesized to be the progenitor of verbal language anyway.

Their brains were smaller than expected for a Homo of their size, with an encephalization quotient more similar to the more primitive Australopithecus. However, their brain structure was definitely Homo, with a humanlike frontal lobe, so it’s not clear how intelligent they would have been. There are stone tools in the style of the Early and Middle Stone Age known from this time and place, and no other hominin remains in the area, so it’s likely that they belong to H. naledi.

The chamber where the bones are found is quite hard to access, requiring people to belly-crawl through a tight section and climb up a fifty-foot sharp rock formation. To the tiny and climbing-adapted H. naledi, this was probably a feature: it kept those pesky, oversized H. sapiens out! The fact that they laid their dead to rest here intentionally and brought light to work and navigate by means that they were likely capable of complex, symbolic thought and coordinated, ritualistic behaviors. In my book, they are sophisticated enough to know how to treat a broken leg, and are very curious, but they have a short attention span, sort of like a very gifted eight-year-old. They use fire but don’t have the ability to create it; they took some out of a wildfire once, and now they keep a fire burning in a cave continuously, or else they’d lose it completely. This is not based in fact, but is inspired by a population of H. sapiens native to Papua New Guinea who lost the ability to make fire and never rediscovered it. Friction bows and flint and pyrite are not intuitive!

Fun fact about the excavation of this cave: since the “Superman Crawl” section is only ten inches in diameter, the discoverer put out a want ad on social media looking for small women scientists to perform the excavation, since only they could get in and out while loaded down with tools and specimens. He got sixty applicants and assembled a team of six, who became known as the “Underground Astronauts”.

Homo erectus: “firstfolk”

H. erectus was the first species of human to go intercontinental, expanding from where they originated Africa to colonize much of the Old World and evolving into various daughter species while still living alongside them. They made stone tools and used fire, though it’s unknown to what extent and whether they could create it. Since they were such a long-lasting and widespread species, there was a lot of variation in their physiology, with some populations having very small brains and others having brains nearly as large as modern humans, some having huge, gorilla-like molars and prognathic (protruding) jaws while others had more delicate teeth, and likely some having lighter skin and some darker. This leaves a lot of room for artistic interpretation; whatever my firstfolk are doing, it’s likely some population of H. erectus did it at some point.

Their growth and development was intermediate between chimps and later humans, with babies being born less helpless and growing up faster, precluding as complex of language and culture as slower-growing human species. Similar to chimps, they would probably not have lived as long as us. Their bones were unusually thick - so thick that sometimes their braincases are confused with fossil turtle shells. We don’t really understand why, but it probably would’ve made them quite strong and sturdy; in my book, they are able to lift heavy things, run for hours, and dig away hillsides with ease.

H. erectus remains are associated with butchered remains of all kinds of large herbivores, and they’re the likely culprit in many megafaunal extinctions due to overhunting. However, there isn’t consistent evidence of fire usage at H. erectus sites, indicating that they ate this meat raw. This is further supported by genetic evidence from tapeworms, which are transmitted through raw meat and speciated into human-specific forms at the same time and place H. erectus first originated. In my book, the firstfolk just bite into their raw meat and have the dental equipment to successfully chew it, while the kinfolk (H. sapiens) protagonist does not. But it’s likely that some populations of H. erectus did cook their food, some pounded or cut it with hand axes before eating it, and some just ate it the way my firstfolk do. My hypothesis is that the inability of most H. erectus populations to smoke meat may have been what caused the overhunting: animal protein comes in large packets but goes bad quickly, so whatever the tribe couldn’t eat within a couple days would be left to the hyenas, and then they’d have to go kill a fresh gigantic animal.

In my book, the firstfolk don’t have tents, but instead sleep behind a dug windbreak. This is based on an archaeological site where a ring of piled stones was found associated with H. erectus remains, and one interpretation of this was that it was a low wall intended to break the wind. But other interpretations include that it was a foundation of a larger structure that didn’t preserve, and that it was formed naturally by tree roots or something. I ran with the windbreak idea and had my firstfolk dig one out of a hillside instead of piling stones, since they live on the savanna where stones would not have been easy to find.

We don’t have direct evidence of whether H. erectus had fur or not, but it’s likely they did not because the gene for dark skin, only necessary as protection against the sun if you don’t otherwise have your skin covered, arose long before other hominins had evolved. This also makes sense as an adaptation for persistence hunting in grasslands, which H. erectus is almost always associated with, as it would have allowed them to sweat to keep cool while their prey would eventually fall to heat exhaustion. The tropical populations of H. erectus would therefore likely have been quite dark-skinned.

Because they’re strong, smooth-skinned, and very fit from running miles and miles every day, the other characters in my book think the firstfolk are very beautiful. In some ways, my firstfolk are Proud Warrior Race Guys - they’re impressive physical specimens and they’re very set in their traditional ways of doing things, refusing to adopt new technology like fire and hafted spears even when other hominins evolve and offer it to them. But at the same time, they’re very goofy. I had fun naming my firstfolk very stereotypical “caveman” names, like Hoona, Drig, Onga, Gog, and literally Thag. They also speak like cavemen, talking in the third person and omitting most articles.

One completely speculative element I gave to the firstfolk is colorblindness. The code for the three cones in your eyes that allow you to see color, red, blue, and green, is located on the X chromosome, and some people have faulty code for either the red or the green cone, making red and green appear the same to them. However, colorblindness is much more common in men than women, because they don’t have a backup copy of the X chromosome. For a woman to be colorblind, she has to have two faulty copies that are faulty in the same way, which is quite unlikely. In my book, the firstfolk have two different types of X chromosomes, both of which are faulty in different ways: one type codes for red and blue cones, while the other type codes for green and blue. This way, all men and half of women will end up with only two cones and be colorblind, while the other half of the women have all three cones and be able to distinguish red and green, since they have two different varieties of X chromosome.

The probable reason colorblindness is not weeded out by natural selection is that it can be adaptive when you’re trying to spot camouflaged prey, since most camo assumes color vision. During WWII, the American and British armies employed colorblind people to spot enemy hides from the air. So it’s not crazy to imagine a population that intentionally has both color-seers and camo-spotters. The reason I gave them this trait is because I wanted one of my fantasy races to be matriarchal, rather than just egalitarian. Matriarchy has never occurred in humans because there are some types of foraging men are better at (like big game hunting) and there are some types that men and women are equally good at (like gathering plants), but there aren’t any that women are strictly better at. If all the men are colorblind, the non-colorblind women would be better at tracking, would bring in more calories, and would control access to food.

One ape species that is actually matriarchal is bonobos, in which the troop is run by a matriarch who gains power through consensus among other females. They speciated from their common ancestor with chimps due to geographic isolation, where bonobos ended up on the side of the river with more resources and less competition, making them peaceful and cooperative, while chimps ended up on the wrong side of the tracks, with few resources and competition from gorillas. (Minute Earth has a good video explaining this.) The reason this made bonobos matriarchal isn’t exactly clear, and it’s different from my firstfolk, but I think the matriarchal society that results would’ve had some similarities, even though the origin is different. Like bonobos, my firstfolk are promiscuous, having casual sex with anyone else in the tribe and using sex as a tool of social communication, especially as a way to make up after disagreements. However, since this is a young adult novel, that element of firstfolk culture is not very thoroughly explored.

Conclusion

Well, I ended up writing a whole lot about only two of the five species that appear in my book, and I think I’m going to stop there for now. The page image is a treefolk character in the book; you can see her small, sloping forehead and weak jaw, but beyond that I wanted her to be pretty. At some point soon I’ll write a follow-up post about the other three hominin species; the Denisovans, which I call “dragonfolk”, have a culture that’s particularly fleshed out in my book. If you want to read this book and know any authors, agents, or editors, I would appreciate a connection :)